2. SHAKE-SPEARE a Pseudonym?

The Sonnets

YES IT IS. There is no other explanation for the hyphen. As soon as the epic poems Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594) by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE were published, Henry Willobie wrote: “And Shake-speare paints poor Lucrece rape” (Willobie his AVISA, 1596).

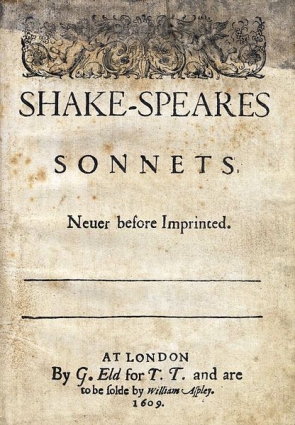

Furthermore, the first time that the name appears on the frontpage of a QUARTO, it was written with a hyphen. Pirate copies of Titus Andronicus, The Taming of a Shrew and 2+3Henry VI were published in 1594 and 1595, without naming the author. In 1597 and 1598 two good quartos of Richard the second and Richard the third were published, naming “William Shake-speare” and “W. Shake-speare” as the author. Eleven years later, the sonnets were published under the title: “SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS”.

The

scholar and poet John Davies of Hereford continued in this tradition in 1611

when he wrote an epigram to Shakespeare with the dedication: “To our English

Terence Mr. Will. Shake-speare”. The rhetoric teacher, John Vicars, refers to

the famous poet (“celeber poeta”) in 1621 with the words: “qui a quassatione et

hasta nomen habet” – ‘who takes his name from the shaking and spear’. In his

introductory poem to the Folio edition of 1623 Ben Jonson gives an obvious clue

to the reader: “his well torned and true filed lines, / In each of which he

seems to shake a lance”.

The actor, part owner of “The Globe” theatre and money lender from

Stratford-upon-Avon always wrote his name “Will Shaksper” or “Shakspere”.

William Beeston, the son of an actor colleague of Shaksper, said of his writing

abilities: “if invited to write he was in paine” (Aubrey’s

Brief Lives, ed. 1898).

Why should such a man call himself Shake-speare, the shaker of the spear?

Furthermore, how can we expect him to write an epic poem in courtly style after

his “lost years”, dedicating it, with an aristocratic turn of phrase, to the

young Earl of Southampton? “...only, if your honour seem but pleased, I account

my self highly praised, and vow to take advantage of all idle hours, till I

have honoured you with some graver labour.”

A closer look at this pseudonym reveals more about the man who called himself

Shake-speare. The mental picture of the SPEAR SHAKER is taken from the goddess

Pallas Athena (=Minerva =Bellona) who was literary born shaking a spear. The

goddess came to the world out of her father Zeus' head - in full armour. As

well as being the goddess of palaces, military strategy crafts and weaving, she

was foremost the guardian of art and wisdom. In her hand a spear, not as a sign

of aggression but of vigilance. The Elizabethans were thoroughly familiar with the

twentyeighth Homeric Hymn: “Athena sprang quickly from the immortal head and

stood before Zeus who holds the aegis, shaking a sharp spear.” What better name

could there be for a warrior poet?

In Lucian's Dialogues of the Gods, Virgil's Aeneid

and Apuleius’ Golden Ass, Pallas

Athena was known as the Goddess of the thundering (or quivering) spear. In Charles

Estienne's Dictionarium Historicum,

Geographicum, Poeticum (1553), one of the established dictionaries on the

classics, the entry on Pallas is as follows: “The helmet and shield lend her a

formidable appearance, her lance seems to swing in her hand.”

The play-write and hater of theatre, Stephen Gosson, writes in Playes confuted in five Actions (1582):

“Tertullian teacheth us that every part of the preparation of playes was

dedicated to some heathen god or goddess; the penning to Minerva.”

Abraham Fraunce wrote in 1592 (The Third

part of the Countesse of Pembrokes Yuychurch): “Pallas was so called

because shee slew Pallas a Gyant: or, of shaking her speare.”

In other words, generations of scholars and authors had paved the way for this

choice of pseudonym.

We cannot overlook that Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford (1550 – 1604), “one of

the best in comedy amongst us” (Francis Meres, Palladis Tamia, 1598) and the “most excellent” among the poets in

her Majesty’s Court (William Webbe, A

Discourse of English Poetry, 1586),

was associated with Pallas Athena (Minerva) by two separate literary

contemporaries. Gabriel Harvey praised the Earl in 1578: Your countenance is

shaking spears [“vultus tela vibrat”]; and Edmund Spenser, alias Colin Clout,

alias Pierce, alias E.K., 27 years old, wants the dramatist Edward de Vere,

alias Cuddie, to write heroic histories, to bring the muses onto the stage

accompanied by Bellona, goddess of war. (See: Kurt Kreiler, Anonymous SHAKE-SPEARE, pp. 125-127.)

William Shake-speare may well have been aware of the erotic connotations of the

name. We can safely assume that he read the Epithalamium of Giovanni Giovano

Pontano (1429-1503), telling a young man what was expected of him on his

wedding night: “When the bride is overwhelmed with the heat of her desire in

your passionate embraces, then is the time to attack- my friend, you must

heatedly shake your spear to inflight the longed-for wound on her.” – “Telum

cominus, hinc et inde vibrans,/ Dum vulnus ferus interferus amatum”. (Pontani carmina, Firenze 1902, vol.2, p.

262)

Sources:

HOMERIC HYMN 28 ( probably written in the seventh century BC)

To Pallas

Pallas-Minerva's Deitie, the renown'd,

My Muse in her variety must resound;

Mightie in counsailes; whose Illustrous Eyes

In all resemblance represent the skies.

A reverend Maid of an inflexible Minde;

In Spirit and Person strong; of Triple kinde;

Of Jove-the-great-in-counsaile's very Braine

Tooke Prime existence; his unbounded Brows

Could not containe her, such impetuous Throws

Her Birth gave way to that abrode she flew,

And stood in Gold arm'd in her Father's view,

Shaking her sharpe Lance. All Olympus shooke

So terriblie beneath her that it tooke

Up in amazes all the Deities there;

All Earth resounded with vociferous Feare;

The Sea was put up all in purple Waves,

And settld sodainly her rudest Raves;

Hyperion's radiant Sonne his swift-hov'd Steedes

A mighty Tyme staid, till her arming weedes,

As glorious as the Gods;, the blew-eyd Maid

Tooke from her Deathlesse shoulders. But then staid

All these distempers, and heaven's counsailor, Jove,

Rejoic't that all things else his stay could move.

So I salute thee still; and still in Praise

Thy Fame, and others', shall my Memorie raise.

Tranlated by George Chapman [1624]

VIRGIL (70 BC – 19 BC)

Her body ran with swet, and from the

ground (wee wondred all)

Three times alone she leapt, and thrise her sheeld and speare she shooke.

Aeneid. Book II, translated by Phaer and Twyne, 1573

LUCIAN (c.AD 125 – after AD 180)

What's here ? A woman arm'd leaps on the Plain :

O Iove, thou had'st much mischiefe in thy brain.

No marvell thou wert angry and much paind,

When in thy Pia mater was containd

A live Virago, arm'd, and having spread

Castles and townes and towers about her head ;

She leaps and capers, topt with rage divine,

And danceth (as she treads) the Matachine,

Shakes her steele pointed Lance, and strikes her Tardge,

As if she had the god of War in charge.

Dialogues of the Gods. Vulcan and Jupite, transl. by Thomas Heywood, 1637

CHARLES ESTIENNE (1504-1564)

Fiebat enim simalcrum galea et scuto terribile, et hastam manu tenens, quam

veluti vibrare videbatur.

The

helmet and shield lend her a formidable appearance, her

lance seems to shake in her hand.

Dictionarium historicum ac poeticum,1553

GABRIEL HARVEY (c.1552 – 1630)

Anglia te Patrium iamque experietur Achillem. Perge modo, actutum tibi Mars, tibi serviet Hermes, aegisonansque aderit Pallas pectusque, animumque instruet ipsatuum: iampridem Phoebus Apollo artibus excoluit mentem [...] tu videris, an iam iamque velis pugnare ferox: ego sentio: tota patria nostra putat: feruescit pectore sanguis; virtus fronte habitat: Mars occupat ora; Minerva in dextra latitat: Bellona in corpore regnat: Martius ardor inest: scintellant lumina: vultus tela vibrat: quis non rediviuum iuret Achillem?

England will discover in you its

hereditary Achilles. Go, Mars will see you in safety and Hermes attend you;

aegis-sounding Pallas will be by and will instruct your heart and spirit, while

long since did Phoebus Apollo cultivate your mind with the arts. [...] You are

being observed as to whether you would care to fight boldly. I feel it; our whole

country believes it; your blood boils in your breast, virtue dwells in your

brow, Mars keeps your mouth, Minerva is in your

right hand, Bellona reigns in your body, and

Martial ardor, your eyes flash, your countenance is

shaking spears: who wouldn't swear you Achilles

reborn?

To the Earl of Oxford, In: Gratulationes Valdinenses,

1578

EDMUND SPENSER (1552-1599)

In Cuddie is set out the perfect pattern of a Poet, which finding no maintenance of his state and studies, complaineth of the contempt of Poetry, and the causes thereof ...

PIERCE [= Edmund Spenser].

Cuddie, for shame [modesty] hold up thy heavy head,

And let us plan with what delight to chase:

And weary this long lingering Phoebus race.

Whilom [some time before] thou wont the shepherds lads to lead,

In rimes, in riddles, and in bidding [prisoner's] base:

Now they in thee, and thou in sleep art dead?

CUDDIE [= Edward de Vere].

The pretty ditties, that I wont devise,

To feed youthes fancy, and th’offspring,

Delighten much: what gain have I for that?

They have the pleasure, I a slender pr[a]ise.

I beat the bush, the birds to them do fly:

What good thereof to Cuddie can arise?

PIERCE.

Abandon then the base and viler clown,

Lift up thyself out of the lowly dust:

And sing of bloody Mars, of wars, of jousts,

Turne thee to those, that bear the awful crown.

To r’doubted Knights, whose woundless armour rusts,

And helms unbruised vexen daily brown.

CUDDIE.

O if my temples were distained with wine,

And girt in girlands of wild Yvie twine,

How I could rear the Muse on stately stage,

And teach her tread aloft in buskin fine,

With queint* Bellona in her order.

E.K.'s gloss

*Queint) strange Bellona; the goddess of battle, that is Pallas, which may therefore well be called queint for that (as Lucian saith) when Iupiter her father was in travail of her, he caused his son Vulcan with his axe to hew his head. Out which leaped forth lustily a valiant damsel armed at all points, whom seeing Vulcan so fair & comely, lightly leaping to her, proffered her some courtesy, which the Lady disdaining, shaked her speare at him, and threatened his sauciness. Therefore such strangeness is well applied to her.

ÆGLOGA DECIMA [October]. In: The Shepheard's Calender, 1579 [shortened, modern spelling]

ABRAHAM FRAUNCE (c.1559 - 1593)

Pallas was so called because shee slew Pallas a Gyant: or, of shaking her speare.

The Third part of the Countesse of Pembrokes Yuychurch, 1592

HENRY WILLOBIE [pseud.]

Yet Tarquyne pluckt his glistering grape,

And Shake-speare paints poore Lucrece rape.

CANT. XLIIII.

H. W. being sodenly infected with the contagion of a fantasticall fit, at the first sight of A, pyneth a while in secret griefe, at length not able any longer to indure the burning heate of so fervent a humour, bewrayeth the secresy of his disease unto his familiar frend W. S. who not long before had tryed the curtesy of the like passion, and was now newly recovered of the like infection; yet finding his frend let bloud in the same vaine, he took pleasure for a tyme to see him bleed, & in steed of stopping the issue, he inlargeth the wound, with the sharpe rasor of a willing conceit, perswading him that he thought it a matter very easy to be compassed, & no doubt with payne, diligence & some cost in time to be obtayned. &c.

CANT. XLVII.

W. S.

Well, say no more: I know thy griefe,

And face from whence these flames aryse,

It is not hard to fynd reliefe,

If thou wilt follow good aduyse:

She is no Saynt, She is no Nonne,

I thinke in tyme she may be wonne…

Willobie his AVISA, Or The true Picture of a modest Maid, and of a chast and constant wife, 1596

JOHN MARSTON (1576 – 1634)

Come, Cressida, my Cresset light,

Thy face doth shine both day and night;

Behold behold, thy garter blue,

Thy knight his valiant elbow wears,

That when he shakes his furious Speare

The foe in shivering fearful sort

May lay him down in death to snort.

Histriomastix, performed 1599

M. L. [= Gabriel Harvey ?]

Dear nurslings of Parnassus be not won

by rash credulity to leave to time

a shameful calendar of deeds misdone

by those which never yet committed crime;

My selfe instead a reverend wit have blamed

without desert, whereof I am ashamed.Pardon sweet wit (which has a liberal part

of pure infusion in thy happy brain)

My sorowing sobs have bloodless left my heart,

that giddy rage so clear a spring did stain,

let worthless lines be scattered here and there,

but verses live supported by a speare.

Envies Scourge and Vertues Honour by M. L. (c.1604)

THOMAS VICARS (1589 – 1638)

Quo quidem in loco recenset ille poetas quosdam, quorum et numeros et laudavere sales nostri, de quibus forsitan non immerito Anglia nostra gloriatur, Galfridum Chaucerum, Edmundum Spencerum, Michaelem Draytonem, et Georgium Withersium. Istis annumerandos censeo celebrem illum poetam qui a quassatione et hasta nomen habet, Ioannem Davisium, et cognominem meum, poetam pium et doctum Ioannem Vicarsium.

That one [Charles Butler ,1597] compiled a list of the most important authors of the English literature, quite rightly praising the names of Geoffrey Chaucer, Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton und George Withers. To these, I think, should be added that famous poet who takes his name from the shaking and spear – and John Davies - and a pious and learned poet who shares my surname: John Vicars.

Χειραγωγία, Manuductio ad Artem Rhetoricam…in usum Scholarum, 1621

BEN JONSON (1572-1637)

And such wert thou ! Look how the father's face

Lives in his issue, even so the race

Of Shakspeare's mind and manners brightly shines

In his well torned and true filed lines,

In each of which he seems to shake a lance,

As brandisht at the eyes of ignorance.

To the Memory of My Beloved Master William Shakspeare, 1623