6. Ben Jonson's Forgery

A Falsification.

On the surface of it, nobody seemed to be greatly stirred by the death of the Lord Great Chamberlain. Nothing is known of the funeral. If there were any obituaries, no report of them has survived.

The literary friends and colleagues – John Lyly, Anthony Munday, George Chapman, Thomas Lodge, John Florio and Sir John Harington – were faced with a dilemma: The Earl of Oxford, courtier of the late Queen Elizabeth had died. The fact that he was also shake-speare was a matter that nobody dared mention.

Nathaniel Baxter (c. 1550–1611) wrote a long allegorical poem in 1606 entitled: Sir Philip Sidney’s Ouránia, in which Sir Philip bends down from the clouds. Baxter dedicates this poem to Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, and her daughter in law, Susan de Vere, Countess of Montgomery – Oxford’s youngest daughter, “the first of Cynthia’s ladies”:

The first was Vera daughter to an Earl,

Whilom a Paragon of mickle might:

And worthily then termed Albion’s Pearl,

For bounty in expence, and force in fight,

(Me list to give so great a prince his right)

In all the triumphs held in Albion soil

He never yet receiv’d disgrace or foil.

Onely some think he spent too much in vain,

That was his fault; but give his honour due,

Learned he was, just, affable and plain;

No traitor, but ever gratious, and true:

Gainst Princes peace, a plot he never drew.

But as they be deceiv’d that too much trust;

So trusted he some men, that prov’d unjust.

Weak are the wits that measure Noble-men,

By accidentall things that ebb and flow;

His learning made him honourable then,

As trees their goodness by their fruits do show,

So we do Princes by their vertues know.

For riches, if they make a King, tell then:

What differ poorest Kings from poorest men?

In his work: The Revenge of Bussy d’ Ambois (1609) the dramatist, George Chapman (1559–1634) shows the Earl in a very good light. Bussy is a tragic hero in the reign of Henri III. The protagonist of The Revenge of Bussy D’Ambois is Clermont D’Ambois, a fictitious brother of Bussy, Chapman invented. Chapman puts the following words in Clermont D’Ambois’ mouth:

I overtook, coming from Italy, / In Germany, a great and famous Earl / Of England; the most goodly fashion’d man /I ever saw: from head to foot in form / Rare and most absolute; he had a face / Like one of the most ancient honour’d Romans /From whence his noblest family was deriv’d; / He was besides of spirit passing great, / Valiant and learn’d, and liberal as the sun, / Spoke and writ sweetly, or of learned subjects, / Or of the discipline of public weals. (The Revenge, III/1).

Through Clermont D’Ambois , Chapman describes Oxford as a noble, aristocratic and individualistic person:

Had rather make away his whole estate / In things that cross’d the vulgar, than he would / Be frozen up stiff (like a Sir John Smyth, / His countryman) in common nobles’ fashions, / Affecting, as the end of noblesse were, / Those servile observations (II/4).

Henry Peacham, the son of the old curate Henricus Peacham, praised the literary talents of the Earl of Oxford but had nothing at all to say about “William Shakespeare”:

In the time of our late Queene Elizabeth, which was truly a golden Age (for such a world of refined wits, and excellent spirits it produced, whose like are hardly to be hoped for, in any succeeding Age) above others, who honoured Poesie with their pens and practise (to omit her Majesty, who had a singular gift herein) were Edward Earl of Oxford, the Lord Buckhurst, Henry Lord Paget; our Phoenix, the noble Sir Philip Sidney, M. Edward Dyer, M. Edmund Spenser, M. Samuel Daniel, with sundry others; whom (together with those admirable wits, yet living, and so well known) not out of Enuy, but to avoid tediousness I overpass. Thus much of Poetry.

(The Compleat Gentleman, 1622)

A year after the FOLIO the poet and writer, Gervase Markham (1568–1637) wrote an enthusiastic memorial to the seventeenth Earl of Oxford:

“this nobleman breaks off his gyves, and both in Italy, France, and other Nations, did more honour to this Kingdom then all that have travelled since he took his journey to heaven. It were infinite to speak of his infinite expence, the infinite numbers of his attendants, or the infinite house he kept to feed all people; were his president now to be followed by all of his rank, the Pope might hang himselfe for an English Papist, discontentment would not feed our enemies’ armies, nor would there be either a Gentleman or Scholar to make a mass-priest or a Jesuit. That he was upright and honest in all his dealings, the few debts left behind him to clog his survivors were safe pledges; and that he was holy and religious the Chapels and Churches he did frequent, and from whence no occasion could draw him; the alms he gave (which at this day would not only feed the poor, but the great man’s family also) and the bounty which Religion and Learning daily took from him, are trumpets so loud, that all ears know them; so that I conclude, and say of him, as the ever memorable Queen Elizabeth said of Sir Charles Blount, Lord Montjoy, that he was honestus, pietas, & magnanimus.”

(Honor in his Perfection. A Treatise in Commendation of the Vertues of Henry Earle of Oxenford, Henry Earle of Southampton ... London 1624)

At the juncture when we expect to see the secret of Oxford’s pseudonym made generally known, we find it being guarded more fearfully and closely than ever.

Why?

The relatives of the Earl of Oxford now had control over the publishing rights to his works: Oxford’s widow, Elizabeth Trentham Countess of Oxford (c. 1563–1612), her son Henry de Vere, 18th Earl of Oxford (1593–1625) along with the three daughters from his first marriage: Elizabeth de Vere, Countess of Derby (1575–1627), Bridget de Vere, Baroness Norris of Rycote (1584–1631) and Susan de Vere, Countess of Montgomery (1587–1628).

On 27 December 1604, six months after the death of her father, Susan de Vere married Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery (1584–1650), the son of Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (1561–1621). (As we recall, Mary Herbert was the learned and beautiful sister of Sir Philip Sidney.) Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery and his elder brother, William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1580–1630), whom Lord Burghley wanted to see married to Oxford’s second daughter Bridget de Vere, were (what a surprise) the commissioners and financiers of Shakespeare’s “First Folio” (1623).

Why did the de Vere family tardy so much over the publication of Oxford’s works? Why didn’t they want their name to be involved with the pseudonym william shakespeare – even after the death of the author?

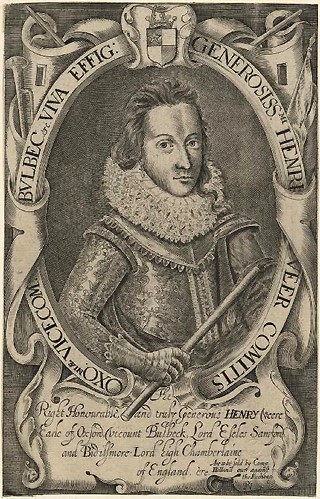

Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke / 1st Earl of Montgomery

After the publication of the “good quarto” from Hamlet, Prince of Denmark in 1604 (“enlarged to almost as much again as it was, according to the true and perfect copy”) the series of “true copies” was interrupted. The straggler, a surreptitiously printed edition, appeared in 1608: M. William Shak-speare: his true chronicle historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three daughters. In 1609 finally came: The historie of Troylus and Cresseida .. Written by William Shakespeare. This work had waited for six years for its publication after its entry in the Stationers’ Register in 1603.

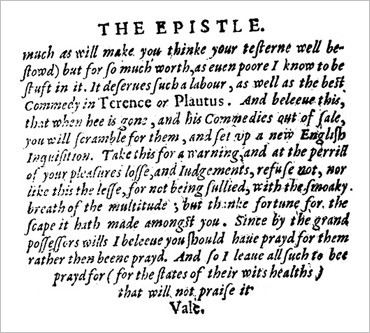

In the anonymous foreword: “A never writer to an ever reader. Newes” we read:

And believe this, that when he [the author] is gone, and his Commedies out of sale, you will scramble for them, and set up a new English Inquisition. Take this for a warning, and ... thank fortune for the [e]scape it hath made amongst you. Since by the grand possessors’ wills I believe you should have prayed for them rather than been prayed.

Search as we may, we cannot find a foreword to any of Shakespeare’s plays in the years between 1594 and 1608. And now, all of a sudden an anonymous “never writer” is pontificating about an “English inquisition” when “the author is gone and his comedies out of sale.”

Of course the author’s “gone”! Were he still with us he wouldn’t have hidden behind a “never writer”. There might be those who think that with the term “grand possessors”, an acting troupe is meant, a concept that can be ruled out by the fact that no acting troupe could possibly own publication rights to Shakespeare’s works. The “grand possessors” are, of course, “the grandees”, the noble owners of Shakespeare’s manuscripts: Oxford’s beneficiaries, who do not intend to allow Shakespeare’s comedies to leak through to the public within the foreseeable future.

The “never writer” was proven right, not a syllable was to be seen until the publication of The Tragedy of Othello, thirteen years later.

We do not know if the family intended to publish further quartos after the “pirated” King Lear and Troilus and Cressida (there were still another nineteen plays still unprinted); if they did, then an event which occurred in the summer of 1609 could only be described as a catastrophe, (at least from their point of view).

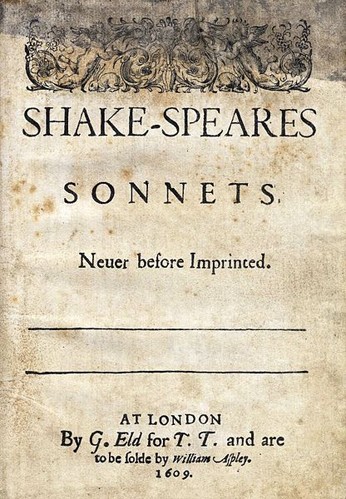

The vexing Thomas Thorpe published shake-speares sonnets. These 154 poems, originally intended to demonstrate that all aspects of life could be expressed in verse, also describe, however, an amour fou that, in the eyes of the family, amounted to a huge scandal.

At the court of King James a lot of people knew who was behind the name: “shake-speare”. And now this bookseller Thomas Thorpe comes along and has the audacity to publish an unabridged version of the most compromising works. To add insult to injury he adds a personal message to the “begetter” (author) of the poems.

T O . T H E . O N L I E . B E G E T T E R . O F .

T H E S E . I N S U I N G . S O N N E T S .

M R . W . H . A L L . H A P P I N E S S E .

A N D . T H A T . E T E R N I T I E .

P R O M I S E D .

B Y

O U R . E V E R - L I V I N G . P O E T .

W I S H E T H .

T H E . W E L L - W I S H I N G .

A D V E N T U R E R . I N .

S E T T I N G .

F O R T H .

T . T .

The amour fou between the Earl of Oxford and “Master W. H.” and “The Dark Lady” would now be common knowledge, should anyone at court take the trouble to read between the lines. The trouble was that the “Dark Lady” now hoped to entertain King James and his retinue at Havering-atte-Bower -and “Master W. H.”, to whom Shakespeare once wrote “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end” was now a Knight of the Garter and the governor of the Isle of Wight. Hardly likely that this rugged, military man would be thankful for being put on public show as the fair youth of the Sonnets.

There was far worse to be feared than embarrassment. A diligent study of Shake-speares sonnets could easily result in a reconstruction of the three way relationship between Oxford, Southampton and Elizabeth Trentham, thereby revealing the possibility that Henry de Vere was the illegitimate son of the Earl of Southampton. It was therefore imperative, for the Countess of Oxford, that the pseudonym “William Shakespeare” never become associated with her deceased husband. The sonnets immediately disappeared from the shelves of the book stores, only to reappear in 1640 in an abridged, disguised publication.

The Two Henries. Henry de Vere, 18th Earl of Oxford, and

Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton

Thomas Thorpe was a lot of things, but he certainly wasn’t fussy. The number of mistakes in shake-speares sonnets led one to the assumption that the preparation of the publication was, at best, “casual”. He also added an appendage that presented serious problems for future generations. Thorpe attributed this poetic appendage with the title A Lover’s Complaint, without any apparent reason, to Shakespeare. (An assumption that scholars were happy to leave uncontested.) The truth came to light 395 years later when Professor Brian Vickers conducted an historical, philological analysis and found that these sentimental, didactic lamentations probably came from John Davies of Hereford. (It is quite likely that Hereford gave the original manuscript of Shakespeare’s sonnets to Thorpe and, as a return favour, Thorpe printed A Lover’s Complaint pretending it came from Shakespeare.)

We are still faced with the question: “Who wrote the foreword to Troilus and Cressida?” Who was the “never writer to an ever reader” who, almost ominously, predicted the failing publication of further comedies?

The elusive author is non other than Ben Jonson. The “never writer” an expert in codes, secrets and elegant formulations reveals his identity to the “ever reader” with the following lines:

Amongst all there is none more witty than this [comedy]: And had I time I would comment upon it, though I know it needs not (for so much as will make you think your testern well bestowed) but for so much worth as even poor I know to be stuffed in it.

The drama doesn’t require a comment from the anonymous, on the contrary the anonymous is commenting on the drama, because he has got a role in it. In other words, “he is stuffed in it”. Ben Jonson is referring to his inglorious personification as Ajax – that was his lot in Troilus and Cressida.

Furthermore the anonymous writer makes a reference to the old posy “Ever or Never” as used by George Gascoigne in 1573 and Henry Willobie in 1594 when punning on the use of the name “e.ver”.

The “never writer” also gives himself away in this foreword with his own unique, indeed, Jonsonian plays on words: “a new play, never staled with the Stage, never clapper-clawed with the palms of the vulgar” – “And were but the vain names of comedies changed for the titles of commodities, or of Plays for Pleas; you should see all those grand censors, that now style them such vanities, flock to them for the main grace of their gravities”. He cajoles the potential buyer and tells him to abandon petty minded thrift. For – “you should have prayed for them [the comedies] rather than been prayed”.

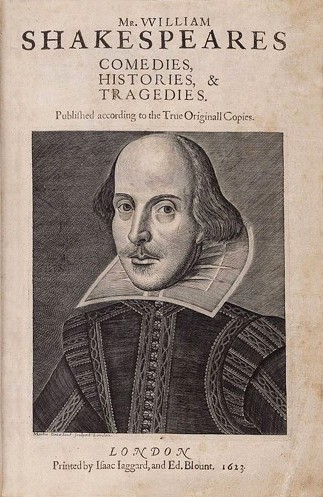

Jonson writes a similar foreword to the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works – this time hiding behind the names of two actors who have never been known to put pen to paper: John Heminge and Henrie Condell.

To the great Variety of Readers ... We had rather you were weighed. Especially, when the fate of all Books depends upon your capacities: and not of your heads alone, but of your purses. Well! It is now publique, & you will stand for your privileges we know: to read, and censure. Do so, but buy it first. That doth best commend a Book, the Stationer saies. Then, how odd soever your brains be, or your wisedoms, make your licence the same, and spare not. Judge your six-pen’orth, your shillings worth, your five shillings worth at a time, or higher, so you rise to the just rates, and welcome. But, whatever you do, Buy. Censure will not drive a Trade, or make the Jack go.

The above is Ben Jonson at his best. No contemporary actor could hold a candle to him.

The nimble Ben Jonson had close connections to Oxford’s heirs. Elizabeth de Vere, Countess of Derby, and Susan de Vere, Countess of Montgomery. Both, especially Susan, used to perform in the masques he wrote for the court of King James. Susan de Vere was a patroness of Jonson, who wrote a flattering poem about her.

William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke

Writing about “The remarkably unremarked association between William Shakespeare and William Herbert, the 3rd Earl of Pembroke”, Robert Macklin, the Australian author and scholar says:

Pembroke has long been the official patron of Ben Jonson, their acquaintance going back to Jonson’s membership of the second Lord Pembroke’s Men in the 1590s. Irascible and egotistical towards his fellow writers, Jonson is a very different character in his dealings with his patrons in the nobility. And there is no one to whom he is more deeply indebted than William Herbert, the 3rd Earl of Pembroke. – He had been patronised by his mother Lady Mary Herbert for whom he writes one of his finest poems, To Penshurst. In 1603 he dedicates his play Sejanus to Pembroke. Two years later the Earl intervenes to have him pardoned by the King when his Eastward Ho! lands him in jail. He subsequently gives Jonson £20 each year to buy books. He awards him an MA from Oxford. He secures him commissions to write and produce Masques for the Court. His beloved Mary Wroth also commissions works. He is, in short, Jonson’s indispensable patron. For though he is easily the most famous writer and playwright in England, Jonson estimates that his many plays have earned him a mere £200 throughout his career.

As of February 1616, on Pembroke’s instructions, Jonson received the sum of £66 per annum from the royal treasury. (A sum that doubled five years later.) In the same year (1616) a large expensive folio edition of the complete works of Ben Jonson was published. This was the first time in the history of England that such an honour had ever been bestowed on a living author and it was, of course, only possible with the support of a wealthy patron.

Understandably enough, the “great possessors” of Oxford’s manuscripts – Henry de Vere, 18th Earl of Oxford and his three half sisters: Elizabeth, Bridget and Susan (the Dark Lady had died in December 1612) – didn’t only wish to publish Jonson’s works but also those of Edward de Vere. They were faced with the problem: How does one blot out, with a minimum of untruths, the fact that Edward de Vere was the man behind the pseudonym “William Shakespeare” and at the same time, keep the memory of the author alive? For the solution of this literary conundrum and instigating an epic camouflage the family engaged the services of Ben Jonson, the “never writing” author of masques.

Ben Jonson used the luxurious edition of his works (nine plays, thirteen masques, six entertainments and divers poems) to lay the foundations for the legend. As well as the list of characters, he includes a list of actors who performed the respective roles in his plays. He did this to one purpose and to one purpose only. One of the actors who played in Every Man in his Humour (1598) and Sejanus (1603) was a certain William Shaksper. Jonson changed his name to Will Shakespeare and Will. Shake-speare.

Susan de Vere, Countess of Montgomery, as “Tomyris” in The Masque of Queenes

by Ben Jonson, 1609. Drawing by Inigo Jones.

Perhaps Jonson started to work on the legend even earlier. The first draught of William Shaksper’s last will and testament, which had first been written in January 1616, had been altered on 25 March 1616 (as demonstrated by Detobel in 2005). In the first draught, there had been no arrangements made for his partners: John Heminge, Richard Burbage and Henry Condell. It would appear that Will Shaksper had no intent to sign this first draught of his will. We find the formulation often used by semi-literate people: “I have therunto put my Seale”. In the second draught of the will we read: “I have thereto put my hand”. The scrawled signature, however, looks as if it came from a man who could write little more than his own name.

What on earth had happened? Forty five years after the death of Will Shaksper, the Reverend Dr John Ward made inquiries about the death of the poet and he was told: “Shakespear, Drayton, and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting, and it seems drank too hard, for Shakespear died of a fever there contracted.”

In 1621 work begins to gather the Shakespearean plays into the First Folio for publication. Most scholars agree that Jonson is called upon to edit and oversee its production. This seems to be quite logical, why would he otherwise have received £132 per annum? Where would he otherwise have learned about passages in Shakespeare’s works that (according to him) required to be changed? How would he otherwise have got to write such a huge homage to Shakespeare at the start of the Folio?

On 8 November 1623, the first folio was entered into the Stationers’ Register and early the following year it was on sale. The work was dedicated to: “to the most noble and incomparable paire of brethren” William and Philip Herbert, Earl of Pembroke and Earl of Montgomery. As publishers, the names of the two actors mentioned in Shaksper’s second last will were entered, John Heminge and Henry Condell.

Only a couple of pen strokes were necessary to transfer the works of shakespeare to the actor Will Shaksper. First of all, the two never-writers, “Heminge&Condell” wrote a witty dedication to Pembroke and Montgomery and bantered light-heartedly with the reader about their “friend and fellow” Shakespeare (in truth, they never wrote a word). Jonson’s poem to the “sweet swan of Avon” follows, wherein he emphasizes the greatness of Shakespeare.

I therefore will begin. Soul of the Age !

The applause ! delight ! the wonder of our Stage !

My Shakespeare, rise; I will not lodge thee by

Chaucer, or Spenser, or bid Beaumont lye

A little further, to make thee a room :

Thou art a Monument, without a tomb,

And art alive still, while thy Book doth live,

And we have wits to read, and praise to give.

In the following lines the truth gets slightly bent.

I should commit thee surely with thy peeres,

And tell, how farre thou dist our Lily out-shine,

Or sporting Kid or Marlowes mighty line.

And though thou hadst small Latine, and lesse Greeke,

From thence to honour thee, I would not seeke

For names; but call forth thund’ring Aeschilus,

Euripides, and Sophocles to us,

Paccuvius, Accius, him of Cordova dead,

To life againe, to heare thy Buskin tread,

And shake a stage...

The truth is neither insulted nor flatly denied, just packaged a little differently. “And though thou hadst small Latine, and lesse Greeke, from thence to honour thee” means: And though you had only a small number of Latin and Greek borrowings, due to it you are to honour.

Sweet swan of Avon! what a fight it were

To see thee in our waters yet appeare,

And make those flights upon the bankes of Thames,

That so did take Eliza, and our James!

In Ben Jonson’s trick we find that “fear and rashness”, admiration and betrayal, truth and falsification enter into a monstrous alliance. Jonson laughs at Kempe’s joke about the unequal namesake – and builds a comedy of errors around it. He had fashioned a posthumous marionette for Oxford’s surviving family, the shadow of a shadow who lays his puppet’s arms on a stone cushion.

Perhaps Jonson even enjoyed doing it. In this way he could avenge himself on the man whom he so deeply admired and so viciously envied, the man whom he loved to hate and to love. He could convince himself that he had done nothing wrong, at least in the course of time. Furthermore, and most important: It was funny.