9.1. Was the Earl of Oxford the son of Queen Elizabeth?

Was the Earl of Oxford the son of Queen Elizabeth?

NO, most certainly not.

Firstly, there are no open questions concerning the parentage of the 17th Earl of Oxford. Secondly Queen Elizabeth did not have any sexual relations with any man alive.

This unsubstantiated “Prince Tudor theory” (the claim that Oxford is the son of Queen Elizabeth, her lover, or the father of her child) brings the Oxford theory into discredit by blatantly falsifying historical facts; an illustrious example being Roland Emmerich's film “Anonymous”.

Emmerich's film quite rightly supports the theory that Edward de Vere is the author of the Shakespearian works. However, he then goes on to invalidate this very support by coupling it with a fairy tale.

What do we find in the historical sources about the father of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, Lord Great Chamberlain of England (1550-1604)?

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford (1516-1562), was an autocrat, a military leader and an adventurer. (He played a leading role in the siege of Boulogne under the command of Henry VIII.) Furthermore he was an overseer of royal lands and a paramount landowner in his own right. He fought for his convictions wholeheartedly and ruthlessly. His wife Dorothy Neville left him in 1546 after she discovered that he had been unfaithful to her with two different women. Dorothy died in 1648, leaving John de Vere a widower with a nine year old daughter, Katherine.

Shortly after the death of his wife John de Vere was summoned to the Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, who, to all intents and purposes, ruled the country in the name of Edward VI after the death of Henry VIII.

Seymour blatantly misused his position for the purposes of extortion. Firstly, he forced De Vere to promise him his daughter's hand in marriage, then with their future family ties as an excuse, he confiscated vast areas of land from him, along with villages, castles and farms. Furthermore, Seymour forced John de Vere to promise that he would never re-marry.

The warrior John de Vere didn't fall into a depression. He set about producing a male heir. He threw his enemy off the track by announcing his marriage to a certain Dorothy Fosser in Haverhill Suffolk on 2 August 1548. On the 1th of August 1548 he rode to Belchamp St. Paul in Essex where he married Mistress Margery Golding. Nobody knew anything of their plans and, for a time they kept the marriage secret. Somerset's men were left waiting for him at the wrong church.

Hedingham Castle

On 12 April 1550, the future 17th Earl of Oxford was born at Hedingham Castle. This child of rebellion was christened Edward in honour of Princess Elizabeth's half brother, the thirteen year old King Eduard VI. (In the meantime, Edward Seymour had been removed from power.) The young King had a 27 ounce golden mug sent to his newly born namesake as a christening present. (See Documents.)

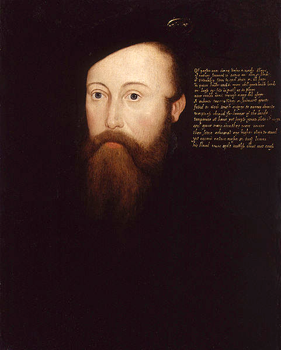

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford (1516-1562)

John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, was a member of one of the oldest and most powerful families in England. It was essential for the survival of the family title that his son and heir be born in wedlock. Furthermore he not the sort of man who you could palm a bastard off onto. Not even a princess' bastard. John de Vere and Margery Golding (half sister of the scholar and translator Arthur Golding) later had a second child, Mary de Vere (1554-1624).

Princess Elizabeth Tudor (born 7 September 1533) according to historic documents never had sexual relations with any man- certainly neither at the age of 13 or 14 with the unscrupulous careerist Thomas Seymour and not at the age of 15 with a mystery lover, indispensable to the newest Hollywood fairy stories.

There was a “Seymour-affair”, but it was no love affair- it was a political affair, whereby the Lord Admiral, Thomas Seymour, the all too audacious brother of the Lord Protector, was beheaded.

Thomas Seymour, 1. Baron Seymour of Sudeley

(c. 1508 - 20-3-1549)

The character of the Lord Admiral Thomas Seymour might easily have walked off the stage of a Shakespeare play. He was handsome, daring and unscrupulous, but he wasn't intelligent enough to become King- and this was his only objective in life.

Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547. Just one month later, Seymour made a brash attempt to secure the 13 year old Elizabeth's hand in marriage, regardless of the danger into which he brought her and himself. His brother, the Lord Protector, had just bestowed the title of Baron on him and appointed him to the position of Lord High Admiral. However Elizabeth refused him.

Princess Elizabeth

„His ultimate intentions are made clear by the fact that some four days after he was rejected by Henry's daughter, he was paying addresses to Henry's widow, to whom he proposed with such charm and ardour that Katherine, who had already buried three husbands, seems to have been led to the altar thirty-four days after the death of her last!“ (Frederick Chamberlin, 1921.)

Even after his marriage to Katharine Parr, the Queen Dowager, in May 1547, Thomas Seymour still nurtured his plans of becoming King with Elizabeth as his Queen. His stand point on the matter was that Katharine Parr wasn't going to live forever, King Edward VI was a sickly youth and his half sister, Mary Tudor, was by no means healthy. He continually made advances to Elizabeth, some veiled, some not so veiled.

According to testimony, given later, by Katharine Ashley, Elisabeth's governess and Thomas Parry, her steward, Katharine Parr originally participated in Seymour's early morning raids into Elizabeth's room, where he would tickle and wrestle with the girl in her nightdress. As gossip began to spread, Kat Ashley, Elizabeth's governess, implored Seymour to quit his bedroom antics with the princess. Indignant, Thomas retorted, 'By God's precious soul, I mean no evil, and I will not leave it!' (It is only fair to add that these statements were extracted from the governess and the “cofferer”, under the threat of torture during their imprisonment in the Tower of London in 1549.) Thomas Parry states that: “The Queen [Katharine Parr] was jealous of him (Thomas Seymour) and the Lady Elizabeth, and on one occasion, coming upon them suddenly, found him holding the Lady Elizabeth in his arms, upon which she fell out with them both, and this was the cause why the Queen and the Lady Elizabeth parted.”

Even so, there is proof that the thirteen year old Elizabeth and her step mother parted on good terms, they both wrote gracious and amicable letters to each other in June and July of 1548 (this would not have been the case if anything indecent had occurred. ) Katharine Parr died in childbirth on 5 September 1548.

After the death of his wife Thomas Seymour continued to conspire against his brother gathering co conspirators around him. He misused his position to facilitate piracy, pocketing the ill-gotten gain himself. He slipped the young King extra pocket money to win him over, on one occasion he even attempted to kidnap the King. He had still not given up his hopes of marrying Elizabeth.

„Elizabeth was now more wary and circumspect, and although the Admiral had gained the active aid of her cofferer Parry and of Katherine Ashley, her governess, he seems to have been unable even to see her before the Protector threw him, his chief supporters, and all of his friends in the entourage of Elizabeth, including Ashley and Parry, into the Tower, while

the princess, treated as one of the conspirators, was confined to Hatfield, under the charge of a representative of the King's Council, Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, and his wife.“ (Frederick Chamberlin, 1921.)

On 22 February 1549 Thomas Seymour was officially charged on 33 counts of treason. One of most serious offences was his attempt to persuade Elizabeth to marry him. Robert Tyrwhitt interrogated the Princess, trying all the time to extract a confession of partial blame. She defended herself both courageously and calmly. She brought counter charges against Tyrwhitt, and put her enemies on the defensive. None of her accuser's efforts could wring a compromising word out of her.

The transcript of Elizabeth's interrogation along with the remarkable letter to the Lord Protector on 28 January 1549 show categorically and uncompromisingly that the idea of a liaison between Elizabeth and Thomas Seymour, be it romantic, sexual or political, is highly absurd.

The Lord High Admiral Thomas Seymour was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 18 January 1549, where he was beheaded on 23 March 1549. The date of his death alone is proof that he was not the father of a child born on 12 April 1550.

According to a breathtakingly stupid theory, propounded by a certain Paul Streitz (2001) - the so called “Prince Tudor theory” (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Tudor_theory) -

Princess Elizabeth gave birth to a child round about the time of Seymour's execution, under the gaze of the Privy Council ! She gave the child into the care of John de Vere who then married a younger woman and presented the 14 month old child to the world as his own newly born son in April 1550. One cannot describe such a theory without reverting to the vernacular of the good Professor Stanley Wells (Stratford!): That's all a lot of crap.

DOCUMENTS.

Letter of 17 April 1550 to Sir Anthony Aucher, Masterof the King’s Jewels and Plate, authorizing delivery of a standing cup as a christening gift from King Edward VI to the 16th Earl of Oxford at the birth of his son, Edward.

THE KING’S MAJESTY’S pleasure by our advice is that ye deliver unto Phillip

Manwaring gentleman-usher to the King’s Majesty, one standing cup, gilt, with a cover

weighing twenty and seven ounces quarter, by him to be delivered as the King’s

Majesty’s gift at the christening of our very good Lord the Earl of Oxford’s son, and

these our letters shall be your sufficient warrant and discharge therein. Given at the

King’s Majesty’s manor at Greenwich the 17th of April the 4th year of his Highness’

most prosperous reign, King Edward the Sixth, 1550.

(British Library MS Add. 5751A, f. 283)

The Confession of Katharine Ashley.

[1549, Feb.]. — Stating what familiarities she has known to take place between the Lord Admiral and the Lady Elizabeth ; that at Chelsea after he was married to the Queen he would come many mornings into Lady Elizabeth's chamber, before she was ready and sometimes before she had risen, and if she were up he would ask her how she did and strike her familiarly on the back or on the buttocks, or if she were in bed he would put open the curtains and make as though he would come at her, and one morning he strove to have kissed her in bed. That one morning at Hanworth the Queen came with him, and she and the Lord Admiral tickled the Lady Elizabeth in the bed.

Stating further what communications she has had with any person touching the marriage of the Lady Elizabeth and the Lord Admiral, and when she last talked with the Lord Admiral and what letters she has written to him since the death of the Queen.

[Calendar]

The Confession of Thomas Parry, the Cofferer of the Princess Elizabeth.

[1549. Feb.]. — Stating what conversations he has had with the Lady Elizabeth concerning her marriage with the Lord Admiral ; and also detailing a conversation between himself and Katherine Ashley on the same subject, in which the latter stated, amongst other things, that the Lord Admiral loved the Lady Elizabeth but too well, and had done so for a good while; and that the Queen was jealous of him and the Lady Elizabeth, and on one occasion, coming upon them suddenly, found him holding the Lady Elizabeth in his arms, upon which she fell out with them both, and this was the cause why the Queen and the Lady Elizabeth parted.

[Calendar]

Princess Elizabeth to Katharine Parr, June 1548

Although I could not be plentiful in giving thanks for the manifold kindness received at your highness' hand at my departure, yet I am some thing to be borne withal, for truly, I was replete with sorrow to depart from your highness, especially leaving you undoubtful of health. And, albeit I answered little, I weighed it more deeper when you said you would warn me of all evils that you should hear of me, for if your grace had not a good opinion of me you would not have offered friendship to me that way, that all men judge the contrary. But what may I more say than thank God for providing such friends to me (desiring God to enrich me with their long life, and me grace to be in heart no less thankful to receive it, than I now am glad in writing to show it)? And although I have plenty of matter, here I will stay, for I know you are not quiet to read. From Cheston this present Saturday.

Your highness' humble daughter,

Elizabeth

(G.B. Harrison (ed.), The Letters of Queen Elizabeth, London 1935, p.7)

Katharine Parr (1512-1548)

Princess Elizabeth to Katharine Parr, 31 July 1548

Although your Highness' letters be most joyful to me in absence, yet considering what pain it is to you to write, your Grace being so great with child, and so sickly, your commendation were enough in my Lord's letter. I rejoice at your health with the well liking of the country, with my humble thanks that your Grace wished me with you till I were weary of that country. Your highness were like to be cumbered if I should not depart till I were weary of being with you; although it were in the worst soil in the world, your presence would make it pleasant. I can not reprove my Lord for not doing your commendations in his letter for he did it; and although he had not, yet I will not complain on him, for that he shall be diligent to give me knowledge from time to time how his busy child doth; and if I were at his birth, no doubt I would see him beaten, for the trouble he hath put you to. Master Denny and my Lady, with humble thanks, prayeth most entirely for your grace, praying the almighty God to send you lucky deliverance. And my mistress wisheth no less, giving your grace most humble thanks for her commendations. Written with very little leisure this last day of July.

Your humble daughter,

Elizabeth

(G.B. Harrison (ed.), The Letters of Queen Elizabeth, London 1935, p.8)

Robert Tyrwhitt to Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, 23 January 1549 (Summary)

Since writing his last letter on the 22nd January, Tyrwhitt deliberated many matters with his Lady's Grace [the Princess Elizabeth], and she hath confessed that at the return of her cofferer from the Lord Admiral he [Thomas Parry] said that Durham Place was to be a Mint, and that the Lord Admiral offered her his own house for the time being to see the King; and he further asked whether, if the Council would consent that the Lord Admiral should have her, she would be content therewith, to which she answered that she would not tell him her mind therein, and demanded who bade him ask that question. He [Parry] replied, nobody, but that he thought he perceived by the Lord Admiral's enquiries that he was given that way.

“In no way will she confess any practice by Mistress Ashley or the cofferer concerning my lord Admiral; and yet I do see it in her face that she is guilty and do perceive as yet she will abide more storms ere she accuse Mistress Ashley. – I do assure your Grace she hath a very good wit and nothing is gotten of her but by great policy.”

— From Hatfield, the 23rd of January.

[Calendar]

Robert Tyrwhitt to Edward Seymour, 25 January 1549, after he had tried a false letter:

"Pleaseth it your Grace to be advertised, that I have showed my Lady your Letter, with a great Protestation that I would not for a 1000 £ to be known of it; . . . notwithstanding, I can not frame her to all points, as I would wish it to be."

[Calendar]

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (c.1506-1552)

Princess Elizabeth to Edward Seymour, Lord Protector, January 28, 1549

My Lord, Your great Gentleness and good Will towards me, as well in this Thing as in other Things, I do understand, for the which, even as I ought, so do I give you most humble Thanks; and whereas your Lordship willeth and counselleth me, as an earnest Friend, to declare what I know in this Matter, and also to write what I have declared to Master Tyrwhitt, I shall most willingly do it.

I declared unto him first, that, after the Cofferer [Thomas Parry] had declared unto me what my Lord Admiral answered for Allen's [Elizabeth’s chaplain] Matter, and for Durham Place [formerly her mother’s], (that it was appointed to be a Mint,) he [ Parry] told me that my Lord Admiral did offer me his House for my Time being with the King's Majestie; and further said, and asked me, whether if the Council did consent that I should have my Lord Admiral, whether I would consent to it or no : I answered that I would not tell him what my Mind was. And I inquired further of him [Parry] what he meant to ask me that question, or who bade him say so: He answered me and said nobody bade him say so, but that he perceived (as he thought) by my Lord Admiral's inquiring whether my Patent were sealed or no, and debating what he spent in his House, and inquiring what was spent in my House, that he was given that way rather than otherwise. And as concerning Kate Ashley [Elizabeth’s governess], she never advised me unto it, but said always (when any talked of my Marriage) that she would never have me marry, neither in Inglande nor out of Inglande, without the Consent of the Kinge's Majestie, your Grace's, and the Council's. And after the Quene [Dowager, Katharina Parr] was departed, when I asked of her [Kate Ashley] what News she heard from London, she answered merrily, ' They say there that your Grace shall have my Lord Admiral, and that he will come shortly to woo you.'

And moreover I said unto him [Tyrwhitt], that the Cofferer sent a letter hither, that my Lord [Admiral] said that he would come this Way, as he went down to the Country. Then I bade her write as she thought best, and bade her shewe it to me when she had done; so she wrote that she thought it not best, for fear of suspicion, and so it went forth. And my Lord Admiral, after he had heard that, asked of the Cofferer why he might not come as well to me as to my Sister : And then I desired Kate Ashley to write again (lest my Lord might think that she knew more in it than he) that she knew nothing in it, but suspicion.

And also I told Master Tyrwhitt that to the Effect of the Matter I never consented unto any such Thing, without the Council's Consent thereunto. And as for Kate Ashley or the Cofferer, they never told me that they would practice it. These be the Things which I both declared to Master Tyrwhitt, and also whereof my Conscience beareth me Witness, which I would not for all earthly Things offend in any Thing; for I know that I have a Soul to save, as well as other Folks have, wherefore I will above all Things have Respect unto this same. If there be any more Things which I can remember, I will either write it myself, or cause Master Tyrwhitt to write it.

Master Tyrwhitt and others have told me that there goeth rumours Abroad which be greatly both against my Honor and Honestie (which above all other things I esteem), which be these; that I am in the Tower; and with Child by my Lord Admiral. My Lord, these are shameful Schandlers [slanders], for the which, besides the great Desire I have to see the King's Majestie, I shall most heartily desire your Lordship that I may come to the Court after your first Determination ; that I may show myself there as I am. Written in haste, from Hatfield this 28th of January. [1549]

Your assured Friend to my little Power,

ELIZABETH.

(G.B. Harrison (ed.), The Letters of Queen Elizabeth, London 1935, pp.9-11)

Robert Tyrwhitt to Lord Protector Edward Seymour, 7 February 1549 (Summary)

Has sent by the bearer the Lady Elizabeth's confession, which is not so full as he would wish. She will in no way confess that either Mistress Ashley or Parry willed her to any practice with the Lord Admiral either by message or writing. They all sing one song, which he thinks they would not do unless they had set the note before. — From Hatfield, the 7th of February.

[Calendar]

Robert Tyrwhitt to Lord Protector Edward Seymour,19 February 1549 (Summary)

On his wife's [Lady Tyrwhitt] declaring to the Lady Elizabeth that she had received a rebuke from the Council for not taking upon herself the office to see her Grace well governed in lieu of Mistress Ashley “her answer was, that Mrs. Ashley was her mistress, and that she had not so demeaned herself that the council should now need to put any mo mistresses unto her. Whereunto my wife answered, seeing she did allow Mrs. Ashley to be her mistress, she need not to be ashamed to have any honest woman to be in that place. She took the matter so heavily, that she wept all that night and lowered all the next day.”

He perceives that she is very loth to have a governor and that she fully hopes to recover her old mistress again, the love she beareth to whom is to be wondered at. If he should say his “fantasy,” thinks it were more meet that she should have two governors than one. She cannot bear to hear the Lord Admiral discommended, but is always ready to make answer thereto.

[Calendar; Haynes State Papers]

Princess Elizabeth to Edward Seymour, Lord Protector, February 21, 1549

My Lord,

Having received your lordship's letters, I perceive in them your good will towards me, because you declare to me plainly your mind in this thing, and again for that you would not wish that I should do anything that should not seem good unto the council, for the which thing I give you my most hearty thanks. And whereas, I do understand, that you do take in evil part the letters that I did write unto your lordship, I am very sorry that you should take them so, for my mind was to declare unto you plainly, as I thought, in that thing which I did, also the more willingly, because (as I write to you) you desired me to be plain with you in all things. And as concerning that point that you write -–that I seem to stand in mine own wit in being so well assured of mine own self -–I did assure me of myself no more than I trust the truth shall try. And to say that which I knew of myself I did not think should have displeased the Council or your grace. And surely the cause why that I was sorry that there should be any such [governess] about me was because that I thought the people will say that I deserved through my lewd demeanor to have such a one, and not that I mislike anything that your lordship or the Council shall think good (for I know that you and the Council are charged with me), or that I take upon me to rule myself, for I know that they are most deceived that trusteth most in themselves, wherefore I trust that you shall never find that fault in me, to the which thing I do not see that your Grace has made any direct answer at this time, and seeing they make so evil reports already shall be but an increasing of these evil tongues.

(G.B. Harrison (ed.), The Letters of Queen Elizabeth, London 1935, pp.12. And: Frederick Chamberlin,The Private Character of Queen Elizabeth, p. 12)

Literature:

[Calendar] Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House, Volume 1: 1306-1571 (1883), pp. 58-80.

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=111963

[Chamberlin] Chamberlin, Frederick: The Seymour Affair. Scandal at Thirteen. In: The Private Character of Queen Elizabeth, pp. 1-16. (London: Bodley Head, 1921)

http://www.archive.org/stream/privatecharacter00cham#page/n21/mode/2up)

Starkey, David: Elizabeth: Apprenticeship (2000)

Christopher Paul: THE “PRINCE TUDOR” DILEMMA: Hip Thesis, Hypothesis, or Old Wives’ Tale?

http://www.shakespeare-oxford.com/wp-content/oxfordian/Paul_PT_Dilemma.pdf