4.1. Biography I (1550-1583)

From his portraits and these two quaint odd account books we can picture very vividly the nineteen-year-old Earl of Oxford when he lived at Cecil House in the Strand in the year 1569. Rather below medium height, he was sturdy with brown curly hair and hazel eyes. On his head a velvet cap with a plume of pheasants’ feathers fastened on one side. A black satin doublet, velvet breeches, and silk stockings supported by silver buckled garters. On his feet the broad-toed, flat-footed, soft leather shoes of the period. At his side a light rapier, passed through a silver-studded belt. Thus clad he would taken by his guardian down to the river stairs at the bottom of Ivy Lane. The liveried waterman would be ready waiting at the steps with the canopied barge. And so they would go upstream, perhaps, to the Palace at Richmond, where the Queen had sent for her „Turk,“ as she playfully called Lord Oxford, to dance with her, or to play on the virginals.

(Bernard M. Ward, The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, 1550-1604, London 1928)

And in her Majesty’s time, that now is, are sprong up an other crew of Courtly makers, Noble men and Gentlemen of her Maiesties own servants, who have written excellently well, as it would appear if their doings could be found out and made public with the rest; of which number is first that noble Gentleman Edward Earl of Oxford ... For such doings as I have seen of their do deserve the highest price: Th’ Earl of Oxford and Master [Richard] Edwards of her Majesty’s Chapel for comedy and Enterlude.

(George Puttenham, The Arte of English Poesie, 1589)

Edward de Vere (he rhymed his name with ever), the son of the Lord Great Chamberlain John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, and his young wife Margery Golding, was born in Hedingham Castle, seat of the de Veres since the end of the eleventh century. – Hedingham is a Norman motte and bailey castle with a stone keep. Additional buildings were added in the 15th and 16th centuries for living accommodation and for agricultural purposes. These buildings later disappeared.

Hedingham Castle

Aubrey de Vere, 2nd Earl of Oxford fought alongside Richard the Lionheart – and Robert, 3rd Earl was one of the barons who forced King John to sign the Magna Carta in 1215. The following year Hedingham Castle was besieged by King John, and again by the Dauphin of France in 1217. The de Veres were military commanders throughout history and featured at the Siege of Caerlaverock and the famous battles of Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt. John, 13th Earl (1442–1513) fought against Richard III at Bosworth Field after which Henry VII raised him to the rank of “High Admiral of England and Ireland”, and bestowed the hereditary title of “Great Chamberlain” on him and his line. At one time the de Vere family used to own large areas of land but these were greatly reduced as a result of the machinations of the Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset (1506–1552). John de Vere 16th Earl of Oxford had to promise to give his daughter’s hand in marriage to Seymour’s son.

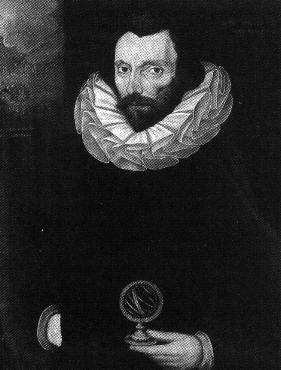

John de Vere

“St. Albans Portrait” of John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford (1516–1562) in the colours of Queen Elizabeth. (The style of the doublet and the high collar with its tiny lace edged in black belongs to the period of the late 1550s or 1560s. Sir Roy Strong has dated the portrait circa 1560. – The wrong caption was put on this picture at a later date.)

John de Vere’s proud, warlike spirit forbade accepting the Seymour clan as his master. On 2 August 1548 he secretly married Mistress Golding, the sister of the scholar Arthur Golding. Their first and only, son Edward was born on 12 April 1550 (modern calender, 22 April). In the meantime, Seymour had been ousted from power. The new monarch Edward VI, just turned thirteen, made the family a present of “One standing cup, gilt with a cover, weighing twenty seven (and a quarter) ounces” to mark the occasion of Edward’s christening.

During the rule of Mary Tudor – which lasted from 1553 until 1558 – the professed protestant John de Vere led a quiet, secluded life in Hedingham Castle. Edward de Vere, the little “Viscount Bolebec, Lord of Escales and Badlesmere”, grew up in the countryside, in the bosom of a well educated family. John 16th Earl was the patron of several theatre companies and a friend of the scholar and diplomat, Sir Thomas Smith (1513–1577).

Sir Thomas Smith

Years later Smith declared that he had taken young Edward into his heart: “The love I bear him because he was brought up in my house.” (Letter to William Cecil, 25 April 1576).

That means that, since he was five or six, Edward de Vere was a frequent guest at Hill Hall, a day’s journey from Hedingham Castle, and residence of the teacher and politician, Thomas Smith. In his office of professor of law at Cambridge University, Smith reformed the pronunciation of the Greek language, he brought the same élan to national economics as he did to theoretical mathematics; a member of the Privy Council, he held the office of Secretary of State and he was a member of parliament.

However, during the reign of Mary Tudor he was forced to live a secluded country life and keep his own council.

After the death of Mary in 1558, Sir Thomas Smith returned to public life. He secured a residency at Cambridge university for the eight year old Edward, not long afterwards (as we can gather from the bill for 2 shillings and four pence) there were broken windows to be accounted for at the prestigious seat of learning and the somewhat premature university career of the young Edward de Vere came to an end.

With the coronation of the young Queen Elizabeth, the office of Lord Great Chamberlain became more prestigious. The 16th Earl escorted the Princess, carrying the ceremonial Sword of State on her way to Westminster Abbey and kneeled before her holding the silver bowl in which she washed her hands. Margery de Vere, Countess of Oxford also assisted in the ceremony.

When Eric the Crown Prince of Sweden asked for Elizabeth’s hand in marriage, he sent his younger brother, John Duke of Finland to England to convey the proposal. The honour of meeting the Duke with his escort of fifty horsemen at Colchester harbour and of hosting the company at Hedingham Castle for a week was bestowed on John de Vere, together with Lord Robert Dudley (later Earl of Leicester, 1532–1588) and Sir Thomas Smith.

Nils Göransson (Gyllenstierna)

Among John of Finland’s entourage was a certain Nicholas Guildenstern (also known as Nils Göransson, Baron Gyllenstierna), who remained in England for a further two years in the hope of persuading Elizabeth to agree to the Swedish marriage.

In August 1561, when Edward de Vere was eleven, Queen Elizabeth visited his parents at Hedingham Castle. During the summer months Elizabeth used to visit carefully chosen nobility taking her entire household with her; advisers, the Privy Council, politicians, diplomats, ladies-in-waiting, gentlemen-in-waiting, courtiers, servants and cooks – all in all, a mobile entourage of more than a hundred people. Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Hedigham Castle in her second year of reign is proof of the high esteem in which she, and her court, held the 16th Earl of Oxford and his wife.

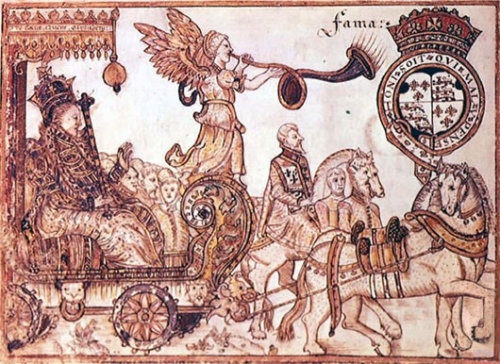

Queen Elizabeth and her entourage

Just one year later, John de Vere took ill. He made out his will on 18 July and died on 3 August 1562.

Legally still a minor, Edward, 17th Earl of Oxford became a ward of the crown until his coming of age. A third of his lands transitory went to the crown. The ward-ship of the land was entrusted to Lord Robert Dudley (later Earl of Leicester). The ward-ship and the care of the young man were entrusted to William Cecil, Baron Burghley, the Queen’s first Secretary of State.

Up until 1571, William Cecil was to see to the housing, feeding and clothing of the young man, also to his upbringing and an education, fitting to his status. These things were, needless to say, not done out of charity; later on, the young Edward de Vere was to foot the bill himself.

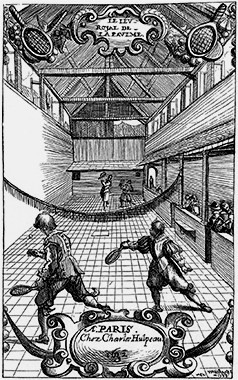

Four weeks after the death of his father, on 3 September 1562, at the age of twelve, the 17th Earl of Oxford arrived in London, accompanied by 140 fellow mourners, to take residence at the home of his new foster parents, William Cecil and Mildred Cooke. Cecil House, his new home, was on the north side of the Strand, close to Whitehall Palace. Cecil House (or Burghley House) was a symmetrical double courtyard brick house of three storeys, with four-storey corner turrets. A central entrance led from The Strand into the front court. At its garden front, with a central bay window and corner turrets, the house looked over gardens and the fields of Covent Garden beyond. The garden included a mount with a spiralling path to its top, a paved tennis court, a bowling alley and an orchard. The library was very well stocked with more than 1500 books and manuscripts. Apart from scholastic and religious works there were also large selections of Greek, Italian, French and English literature.

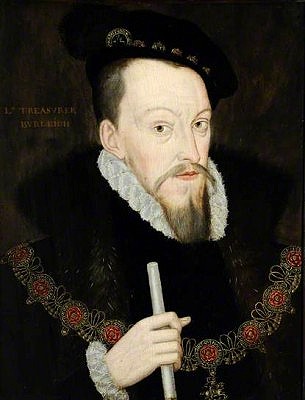

William Cecil, Baron Burghley

Together with three or four boys of the same age, one of whom being Edward Manners, Earl of Rutland, Edward de Vere studied French, Latin, writing, drawing, cosmography (history, philosophy, economics,geography, astronomy, the history of law, and literature appreciation) dancing riding and shooting under the guidance of the best teachers that money could buy.

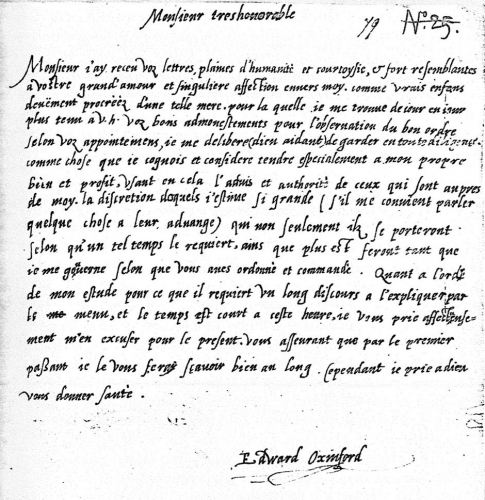

Letter by Edward de Vere at thirteen to Lord Burghley (1563)

Their teacher for cosmography was the eminent scholar, Laurence Nowell (1530–1570). Nowell was one of the founding fathers of Anglo-Saxon studies, a cartographer and antiquarian, he compiled a dictionary of the old English language. He prepared a chronicle of Anglo-Saxon history, and he was one of the first to document the history of Anglo-Saxon law. One of his high guarded possessions must have been the single manuscript of Beowulf, the most prestigious work in the Anglo-Saxon language.

Being a clever politician, Cecil saw to it that his wards maintained good relations with their families. To this purpose, the services of Arthur Golding, (Edward’s uncle) were secured as a tutor. Arthur Golding wasn’t employed for this reason alone, the classical philologist and ancient historian was considered to be one of the best translators of literature of the day. From the dedications on two of his translations we can deduce that Golding spent at least three years with his nephew in Burghley’s residence. Presumably the scholar made good use of Burghley’s excellent library up to the completion of his translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in 1567.

The composer and dramatist, Richard Edwards (1523–1566), Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal probably instructed the young Oxford in music and drama. (We know that the Earl was an accomplished musician and that he performed on stage in Whitehall.) Edward’s duties consisted of; the supervision of the choir practices, composing cantatas and motets for the religious services in the Chapel Royal along with writing and directing masques and comedies to entertain the court.

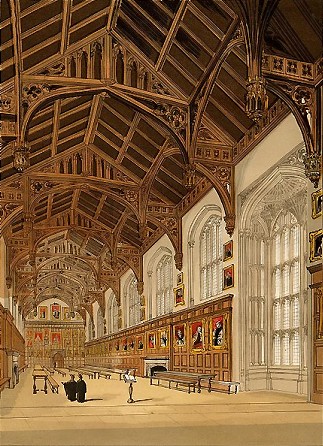

There is a record of Oxford’s having seen Plautus’ Aulularia in King’s College Chapel (Cambridge) at the age of fourteen. The performance was also attended by the Queen and her Lords who found it most enjoyable. On another day the young Earl was given an academic title.

As part of the Christmas celebrations, in 1564 a performance of Richard Edward’s Damon and Phithias was staged in Whitehall Palace. It is quite likely that Edward de Vere was on the cast. – In September 1566 Richard Edwards produced his tragicomedy (or tragic romance) Palamon and Arcyte in Christ Church College in Oxford.

Queen Elizabeth was in attendance and she found the performance to be worthy of the highest praise. Several students who took part in the play enjoyed fame and success in later life: Toby Mathew went on to be the Archbishop of York, John Rainolds – president of Queen’s College, Miles Windsor – research historian, John Argall – philosopher and Thomas Twyne, medic, author and translator.

The Hall of Christ Church

On 1 February 1567 Edward de Vere became a member of Gray’s Inn, one of the Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London, the same Inn of which William Cecil had been a member as a younger man. Just one day later, to mark the feast of the presentation of Jesus at the temple; Ariosto’s comedy I Suppositi which later served as the inspiration for Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew was presented in George Gascoigne’s translation.

On 24 July 1567, the Earl was practising fencing with a tailor by the name of Edward Baynham, in the backyard of Cecil House in the Strand. During this fencing practise a third person, the under-cook, Thomas Brincknell was injured and killed. On the following day, at the coroner’s inquest, a jury of 17 men determined that Brincknell was drunk and that he had caused his own death by running on to the tip of Edward de Vere’s sword. A verdict of “felo per se” (suicide) was reached. Later Sir William Cecil writes in his retrospective diary: “I did my best to have the jury find the death of the poor man whom he killed in my house to be found se defendendo” (causing death in an unavoidable act of self defence).

We are reminded of the grave-yard scene in Hamlet (V/1):

OTHER: The crowner [coroner] hath sate on her, and finds it Christian burial.

CLOWN: How can that be, unless she drown’d herself in her own defence?

In 1569 Thomas Underdown dedicated his translation of Aithiopika to the young Earl, to which he adds the following words: “For such virtues be in your honour, so haughty courage joined with great skill, sufficiencies in learning, good nature and common sense, that in your honour is, I think, expressed the right pattern of a noble gentleman”.

From an accounts book from 1570 we see that, in the course of three months, Edward de Vere purchased: a riding coat, a high quality black cloak, a cambric jacket, a linen jacket, a Spanish jacket made of silk and satin, a pair of black velvet breeches and ten pairs of Spanish boots. In addition to the clothing he also bought a sword, a dagger and several books, among others; the Geneva Bible (in the translation of William Whittington, Geneva 1568), Plutarch’s works in French (translated by Jean Amyot, Paris 1567), and two Italian books. In another quarter the book shop receives the princely sum of four pound six shillings and fourpence for folio editions of Cicero and Plato, in addition to further books and writing materials.

According to the French ambassador, Fénélon, Lord Oxford asked for the Queen’s permission to go to France to support Prince de Condé, the leader of the French Calvinists (Hugenots). Or, that the Queen give him permission to fight against the rebellious troops in northern England. When the young man revealed his plans to the Privy Council there was some considerable surprise. He was, when all said and done, the nephew of the Catholic Duke of Norfolk who was beheaded for treason in 1572.

In April 1570 Queen Elizabeth sent her protégé into the tumult of war- albeit under the auspices of the seasoned veteran Thomas Radcliffe, Earl of Sussex (1526–1583). Again the enemy were Catholic rebels who were being harboured and protected by Scottish Lords. Based in Scotland, they came over the border to raid and pillage English towns. Sussex, indignant over the “ingratitude” of his enemies rode along the banks of the Teviot with 700 horsemen and 1700 footmen to the town of Jedburgh where, encountering hardly any resistance, he burned everything to the ground within a two mile radius.

Thomas Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Sussex

On the morning of 28 April 1570, the Earl of Sussex began with the bombardment of Hume Castle. On the afternoon of the very same day, negotiations for an uncontested surrender of the castle were opened. On condition that the Scots vacated the castle, leaving their weapons and property behind them, hostilities were ended.

Any enthusiastic fervour that the young Earl might have felt for the glories of war seems to have evaporated in the face of what he saw on this campaign. In a poem that was published in 1573 (A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, Divers excellent devises, No. 3) he warns a friend:

This vain avail which thou by Mars hast won,

Should not allure thy flitting mind to field,

Where sturdy steeds in depth of dangers run,

By guts well gnawn by claps that canons yield.

Where faithless friends by warfare waxen ware,

And run to him that giveth best reward:

No fear of laws can cause them for to care,

But rob and reave, and steal without regard,

The fathers coat, the brothers steed from stall:

The dear friends purse shall picked be for pence,

The native soil, the parents left and all,

With Tant tra tant, the camp is marching hence.

On 2 April 1571 just ten days before his twentyfirst birthday the young Lord Great Chamberlain accompanied Queen Elizabeth to the House of Lords where he takes part, during the following weeks, in ten sessions. In the beginning of May, a three day tournament takes place at Westminster to celebrate his coming of age. The Earl of Rutland writes: “Lord Oxford has performed his challenge at tilt, tourney, and barriers far above the expectation of the world, and not much inferior to the other three challengers. The Earl’s livery was crimson velvet, very costly.”

The poet and academic Giles Fletcher (1548–1611) describes Oxford’s appearance in Latin verse:

And should a small hot-blooded war break out he will ride his proud horse into battle with one sure hand on the reins in the other his spear. He shifts in the saddle, he leans forward and fearlessly he spurs the war horse on. The noble animal, thus fired into action pounds the ground with his hooves and, swifter than the wind, he rushes thither where the reins guide him.

Judging things on face value, one could believe that Edward de Vere was being treated with considerable generosity. However, on 1 July 1571 the palace administration presented him with a bill for a total of £7000, made up of £3000 for the costs incurred during his wardship and £4000 for the attestation of his inheritance. He was permitted to pay in instalments, but the balance had to be fully paid before 1581 otherwise the amount would have been doubled.

Given this situation, marrying into a wealthy family hardly seemed like the worst thing that one could do. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, gave the hand of his daughter, in marriage, to the man who used to be his foster son. The bride took a dowry of £3000 into the marriage and Lord Burghley now had family ties with the high nobility.

Burghley’s daughter Anne Cecil was artistic, well read, industrious and pretty. Her upbringing was every bit as good as that of her parents’ noble ward. The marriage took place on the 19th of December 1571, just two weeks after Anne’s fifteenth birthday. It was celebrated with a banquette and a magnificent tournament in Whitehall Palace.

Edward de Vere and his young wife took residence in a building that had been built on the site of the old Savoy Palace in the Strand – a very exclusive location. The residence offered the considerable advantage that “the child”, as he was wont to call her, could spend a lot of her time next door, with her mother. He spent his time writing love poems, but not to his wife. In the spring of 1572 he writes the following lines, both reveiling and concealing at the same time.

This tenth of March when Aries receiv’d

Dan Phoebus rays into his horned head:

And I myself, by learned lore perceiv’d

That Ver approached and frostie winter fled:

I crossed the Thames to take the cheerful air,

In open fields, the weather was so fair.

And as I rowed, fast by the further shore,

I heard a voice which seemed to lament:

Whereat I stay’d, and by a stately doar

I left my boat, and up on land I went:

Till at the last by lasting pain I found,

The woefull wight which made this doleful sound.

Ver (Latin for “spring”, though very close to the name “De Vere”) takes a boat crossing the Thames. He hears the woeful song of a girl for whom the return of spring brings not joy but torment.

‘The lusty Ver which whilome might exchange

My griefe to joy, and then my joys increase,

Springs now elsewhere, and shows to me but strange,

My winters woe therefore can never cease:

In other coasts his sun full clear doth shine,

And comforts lends to ev’ry mould but mine.

What plant can spring that feels no force of Ver?

What flour can flourish where no sun doth shine?’

Suddenly the girl turns round and sees the lively heart-breaker. She gets pale but “the lusty Ver” turns red and flees.

At the instigation of the young Earl Master Bartholomew Clarke wrote a Latin translation of Baldesar Castiglione’s Il Libro del Cortegiano (The book of the Courtier ) with the title Balthasaris Castilionis comitis de curiali sive aulico (London 1571[=72]).

In the foreword, written by Oxford in Latin, the Earl says:

Who has ever taken on a task so noble, so difficult or so illustrious as Castiglione, who depicts the picture and the example of the courtier so clearly. No word fails, not one syllable superfluous, a work that demonstrates the perfection of which humankind is capable. Although nature was never so refined that it was perfect in every way, the nobility that nature gave to man can lend perfection to all things. He who can overcome the baseness in himself can overcome all other obstacles, bringing unimaginable improvement even to nature itself.

Oxford recommended a further book in the summer of 1572; Thomas Bedingfield’s English translation of Cardano’s De Consolatione; the original title page reads Cardanus Comforte, translated into Englishe and published by commaundment of the right Honourable the Earle of Oxenforde... The following scolars; Douce (1807), Hunter (1845), Campbell (1930) and Craig (1934), have all identified Cardano’s “Book of Consolation” as the book that Hamlet reads during his deranged wanderings through the chambers of Helsingør Castle.

By way of a surprise, the Earl includes a rather long poem in the introduction, not to praise the author but to comfort the reader.

The Earl of Oxford to the Reader

The labouring man that tills the fertile soil,

And reaps the harvest fruit, hath not indeed

The gain, but pain; and if for all his toil

He gets the straw, the lord will have the seed.

The manchet fine falls not unto his share;

On coarsest cheat his hungry stomach feeds.

The landlord doth possess the finest fare;

He pulls the flowers, he plucks but weeds.

The mason poor that builds the lordly halls,

Dwells not in them; they are for high degree;

His cottage is compact in paper walls,

And not with brick or stone, as others be.

The idle drone that labours not at all,

Sucks up the sweet of honey from the bee;

Who worketh most to their share least doth fall,

With due desert reward will never be.

The swiftest hare unto the mastive slow

Oft-times doth fall, to him as for a prey;

The greyhound thereby doth miss his game we know

For which he made such speedy haste away.

So he that takes the pain to pen the book,

Reaps not the gifts of goodly golden muse;

But those gain that, who on the work shall look,

And from the sour the sweet by skill doth choose,

For he that beats the bush the bird not gets,

But who sits still and holdeth fast the nets.

The ingenious Earl went on to be the most sought-after entertainer in court society: Elizabeth delighted in his effervescent wit as she was enchanted by his audacity. On behalf of Lord Burghley he greeted the Marshal of France, François Duc de Montmorency, in London and organised a torch-lit tournament to his honour. A month later, in July 1572, Elizabeth and her court went to stay at Edward de Vere’s residence at the village of Havering-atte-Bower, about 15 miles north east of London.

Queen Elizabeth

After a week the Earl accompanied her, along the Avon, on her way back to Warwick Castle where, after dark, he took part in a spectacular show that he had prepared for her.

For a small financial consideration he had recruited about a hundred townsmen from Warwick to act as extras in a mock battle. A wooden construction acted as a fort, cannons (without shot) were fired off and fireworks were set off. Though bloodless, the whole thing was very realistic and those who had never been in battle where quite shaken up. A high point of the performance was a cavalry charge led by Oxford himself. The chronicler of The black book of Warwick wrote:

These battering pieces & chambers were by trains [of powder] fired, and so made a great noise as though it had been a sore assault, having some intermission, in which time the Earl of Oxford and his soldiers to the number of xx [20] with calibres and arquebuses likewise gave divers assaults. Then the fort shooting again and casting out divers fires, terrible to those that have not been in likewise experience, valiant to such as delighted therein and indeed strange to them that understood it not. For the wild fire falling into the river of Avon would for a time lie still and then again raise & fly abroad, casting forth many flashes and flames, whereat the queen’s majesty took great pleasure. It was appointed that the overthrowing of the fort should be a Dragon flying, casting out huge flames & squibs lighted upon the fort, and so set fire thereon to the subversion thereof.

Warwick Castle

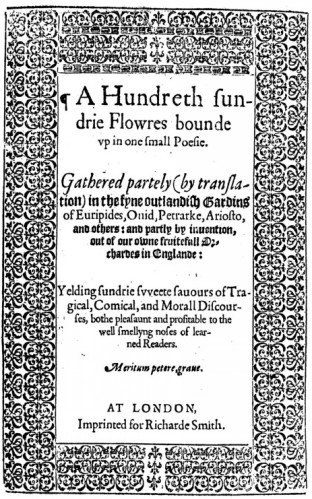

In either May or June of 1573 the anthology A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, Bounde up in one small Poesie was published under the pseudonym “Meritum petere grave” (It is hard to petition for that which one has earned.)

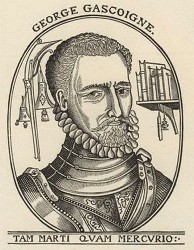

In the epilogue to the German translation of The Adventures of Master F. I. I explained elaborately why this anthology includes two contributions from Edward de Vere and four contributions from the soldier-poet George Gascoigne (c. 1535–1577). Under different pseudonyms, but also under his own name, Gascoigne contributed two dramatic translations (Supposes and Jocasta) and two poetry chapters (“Certain devices of Master Gascoigne” and “The discourse of Dan Bartholmew of Bathe”).

Oxford’s contributions were The Adventures of Master F. I. (which is generally accepted as being the first novel ever published in the English language) – and the poetry collection “Divers excellent devises of sundry gentlemen” which he signed with the posies: “Si fortunatus infoelix” (If fortunate unhappy), “Spraeta tamen vivunt” (Shunned but still alive), “Ferenda Natura” (That which must be endured) and “Meritum petere grave”. (It is hard to beg for that wich one has earned.)

George Gascoigne

Oxford played hide and seek so well that for four hundred years Gascoigne was considered to be the sole author of A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres even though the author left inadvertent clues for the educated reader. In the foreword, he reveals his address “From my lodging near the Strande”, and appears in a poem as “The lustie Ver”. In the heading to the last poem of “Divers excellent devises” he writes: “The absent lover (in ciphers), deciphering his name”. In the poem itself, he goes on to hide his name – Edward de Vere – in a cryptographical manner. Furthermore, although it goes without saying, Edward de Vere’s style of writing is diametrically opposed to that of George Gascoigne.

Oxford’s novel is a story of disappointment and (for that period of time, very modern), love as an “experiment”. Fortunatus Infoelix, a well educated and gallant sixteenth century Knight, falls in love with the Lord’s daughter in law whilst visiting a castle in the north of England. The cavalier decided to conquer the lady’s heart by means of poetry – and is attracted by the ambiguity of Lady Elynor’s refusals, when another woman (Frances) asks the fortunate unhappy Knight to dance with her. Similar to a stage production, the dramatic action of the novel takes place in a limited area, the dialogue is in prose and the characters converse in small groups. – The dialogue is, however, far more quick witted, poignant and audacious than anything hitherto seen in England. The verbal warfare stands in contrast to the erotic intentions, the love affair is compared to military conflict, with battle as its metaphor (see: Kreiler 2006).

Queen Elizabeth I dancing Volta

In the early days of July 1574 the young Earl surprised all around him with a drama in his own life. After an audience with the Queen, whereby she refused to grant a request that he had made, Oxford left London at three o’clock in the morning, procured a large sum of money and in the very next night, set sail for Calais, from whence he travelled to northern Flanders via Bruges. This sudden journey to “enemy territory” caused quite a stir both in England and on the continent (most of Flanders was under Spanish occupation). There was immediate speculation that this peculiar person was on his way to Brussels, to the leaders of the Scottish rebellion. We may assume that he was on the way to his co-author George Gascoigne who had been taken a prisoner of war, one month previously, and was imprisoned in Haarlem. Oxford’s friend Thomas Bedingfield, who the Queen sent to fetch the young Earl back home, caught him up in Zaltbommel on the river Waal and took him back to London. – Zaltbommel was the most southerly bastion of the liberated Netherlands which withstood a Spanish siege for a whole month. Later, the escapade provided inspiration for a tall tale with which Oxford entertained his friends in later days: He said that the timing of Bedingfield’s arrival was most unfortunate. Duke Alba had just appointed him to the position of commander in chief of the Spanish forces. (Oxford’s biographer Alan H. Nelson, an embarrassingly bad – and a breathtakingly boring historian didn’t realize that Oxford was joking.)

The Queen’s Lord Great Chamberlain pestered her so long for permission to travel until she gave in. Equipped with a letter of introduction from the Queen to King Maximilian II and his Tuscan relatives, the twentyfour year old set off, with an entourage of escorts and servants, to travel through France and Italy. Two weeks after his departure it was discovered that Anne Cecil, Countess of Oxford, was pregnant. The Earl didn’t consider this to be reason enough to interrupt his travels.

From Paris, he sent a portrait of himself to his wife and the following reassuring words to his father in law, Lord Burghley.

My Lord, your letters have made me a glad man, for these last have put me in assurance of that good fortune which your former mentioned doubtfully. I thank God therefore, with your Lordship, that it hath pleased Him to make me a father where your Lordship is a grandfather and, if it be a boy, I shall likewise be the partaker with you in a greater contentation. But thereby to take an occasion to return, I am far off from that opinion, for now it hath pleased God to give me a son of my own (as I hope it is), methinks I have the better occasion to travel sith, whatsoever becometh of me, I leave behind me one to supply my duty and service either to my prince or else my country.

“Welbeck portrait” of the 17th Earl of Oxford (1575)

In the Louvre Palace, the young King Henri III introduced Edward de Vere to France’s most influential personages, among others; the entire courtly entourage: the Queen Mother Catarina de Medici – Henri’s sister Marguerite de Valois (Margot) and his brother Hercule-François Duke of Alençon (Monsieur) – Marguerite’s husband, Henri, King of Navarre (latter Henri IV) – the brothers Henri de Lorraine, Duke of Guise and Charles of Lorraine Duke of Mayenne.

Rarely was such a divers collection of personalities gathered under one roof: the scheming Catarina who was largely responsible for the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre – Henri III; one minute moralistic religious fervour, down right debauchery the next – Hercule-François his ambitious brother – the brilliant Queen Margot – Henri de Navarre, the cheerful natured tactician – and the cool, arrogant Henri, Duke of Guise. In the same year –1575 – the Duke of Alençon, being the ringleader of the malcontents, fled the Louvre Palace. Henri de Navarre was soon to follow him after being kept in the palace as a prisoner of the state since 1572. Henri, Duke of Guise advanced to being the leader of the Catholic league and as such, Henri III ordered his murder in 1588.

|

|

|

| Henri III, Roi de France | Catarina de’ Medici | |

|

|

|

| Henri, Roi de Navarre | Marguerite de Valois | |

In the middle of March 1575 Oxford continued his journey, first going to Strasbourg where he stayed with the humanist, Johannes Sturmius, a staunch supporter of Queen Elizabeth.

The Earl stayed in Italy for almost a year and during this time he visited Venice (under the rule of the Doge Alvise Mocenigo I), Padua, Genoa, Milan, Bologna, Florence (under the rule of Francesco de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany) and Siena, more than likely, also Mantua (under Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga) and Ferrara (under Duke Alfonso II d’ Este). On the Monday before lent 1576, two days before the pestilence broke out; he left Venice and rode to Calais via Lyon and Paris through the scourges of the French civil war.

Dirck Barendsz, Venetian ball

On the crossing from France to England on 13 or 14 April 1576 the Earl was attacked by pirates and Dutch marauders; they robbed him and took him prisoner. The Privy Council had to send a diplomat to Prince William of Orange to negotiate the matter.

Thirty years later Nathaniel Baxter writes an account of the journey: “Naked we landed out of Italy, / Enthralled by pirates, men of no regard”. The events had had thirty years to ferment in his lively imagination, so we can allow for mild exaggeration.

The years that follow are among the stormiest in Edward de Vere’s life. Instead of returning to Anne Cecil and his daughter, he deserted his family and accused his wife of infidelity. He laments the loss of his good reputation in a poem which he signs with “E.O.”

Fram’d in the front of forlorn hope past all recovery,

I stayless stand, t’ abide the shock of shame and infamy.

My life, through ling’ring long, is lodg’d in lair of loathsome ways;

My death delay’d to keep from life the harm of hapless days.

My sprites, my heart, my wit and force, in deep distress are drown’d;

The only loss of my good name is of these griefs the ground.

And since my mind, my wit, my head, my voice and tongue are weak,

To utter, move, devise, conceive, sound forth, declare and speak,

Such piercing plaints as answer might, or would my woeful case,

Help crave I must, and crave I will, with tears upon my face,

Of all that may in heaven or hell, in earth or air be found,

To wail with me this loss of mine, as of these griefs the ground.

Help Gods, help saints, help sprites and powers that in the heaven do dwell,

Help ye that are aye wont to wail, ye howling hounds of hell;

Help man, help beasts, help birds and worms, that on the earth do toil;

Help fish, help fowl, that flock and feed upon the salt sea soil,

Help echo that in air doth flee, shrill voices to resound,

To wail this loss of my good name, as of these griefs the ground.

Lord Burghley notes retrospectively: “The Earl of Oxford arrived, being returned out of Italy, he was enticed by certain lewd Persons to be a Stranger to his Wife.”

On 25 April 1576, Oxfords earlier foster parent, the scholar and statesman, Sir Thomas Smith (1513–1577) writes to his friend Lord Burghley: “Your Lordship’s benefits toward him and great cares for him deserveth a far other recompense of duty and kindness, than I hear say he now doth use at his coming over. What counsellors and persuaders he hath so to behave him self, I cannot tell. I am sorry for it, and sorry to hear so much of it.”

All the evidence points to the fact that, Henry Howard, the brother of the executed Duke of Norfolk, wanted to set the seeds of antagonism between Oxford and Lord Burghley in order to win him over to the catholic cause. To this purpose he lied to his cousin about the behaviour of his wife, Anne Cecil, in his absence. Queen Elizabeth responded with a daring manoeuvre: After the execution of the Duke of Norfolk, his home, Castle Rysing was forfeit to the crown. Elizabeth gave this very castle to Oxford in 1577. The aristocratic poet, who was often in financial difficulties couldn’t afford to refuse the gift; neither could he afford to raise suspicions. With that, the friendship between Oxford and Henry Howard was over.

After Oxford’s return to court life, he took over small diplomatic tasks for the French King, Henri III, with whom he communicated through the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau, Sieur de la Mauvissière. A further journey to France was planned in the summer of 1577, but that didn’t take place.

Henri III, who wanted to marry his younger brother to Elizabeth, was a supporter of the policy of non-intervention: non-intervention meaning, in this case, England should not support protestant rebels in France and France should not support catholic rebels in England. On 12 July 1577 the french King writes to Mauvissière telling him to resist any plans that French rebels may have.

Should people make you offers, let them talk, don’t support them and don’t encourage them. By the by, I would have you know that there is much to be said for nurturing the favour of the young Earl of Oxford (“le jeune Comte d’Oxford”). He has voiced his support for the furthering of my interests, as has his cousin, the son of the late Duke of Norfolk [Philip Howard, latter Earl of Arundel]. Secrecy and discretion is of the utmost, take care that no one should feel ill of the two young men and that no suspicion falls on them. I shall soon be sending you a ring which I would have you give to the Earl of Oxford on my behalf as a token of my friendship and my good wishes.

With this letter, the French King makes it clear that he wants no part in Catholic uprisings in England and that the young Earls whom he wishes to befriend have nothing to do with any such rebellions. Nonetheless he doesn’t want his friendship to cause the young men any trouble in the English court.

On 28 July Henri III informs Lord Mauvissière that his cousin, Prince of Condé, the protestant leader, wanted to sail from La Rochelle to England, whereby the English captain John Hawkins (Maistre Hacquin) was to put four or five ships at his disposal. “With the means placed at his disposal, the Prince intends to continue his journey to Germany and there recruit horsemen and mercenaries.” The King adds morosely: “This is adequate proof that [protestant] rebels in my country enjoy the help and support of Elizabeth.”

As soon as he was informed of the matter “le jeune Seigneur” makes the King the very generous offer of contributing to the costs of Prince Condé’s passage. Obviously Oxford connects the offer with the accompaniment of the Prince and diplomatic arbitration.

On 5 September Henri’s reaction to the offer was as follows:

On this matter, I would wish to say that the young Earl of Oxford’s suggestion, concerning his accompanying an English captain, is not possible at this point in time on account of my cousin Prince de Condé’s having changed his plans about travelling to England. Even if he changes his mind I do not wish for the Earl of Oxford to be associated with his activities as this could cause the Queen to suspect and distrust him. – You could however make it clear that his offer and this proof of friendship to my person have greatly pleased me. I am pleased about the present that you have given him and I shall be sending the ring, which is intended for him, shortly.

Once again, the King harbours the exaggerated fear that Oxford’s name could be the subject of gossip if it were known that he had done the King of France a good turn.

On 23 September 1577, Mauvissière answers:

While it gave me great pleasure to inform the young earl of your Majesty’s sentiments regarding the five ships that were, and still are, offered by a certain young man, without cost to your Majesty, I have given him to understand that they will not be necessary in the event of the peace negotiations being successful, as their fortunate beginnings seem to indicate. Furthermore, it would seem that the Prince of Condé no longer intends to come this way.

At the end of the letter the ambassador informs the King of a serious situation:

Le jeune Seigneur summons me to him today to tell me that his sovereign the Queen of England suggested that he, together with the Earl of Leicester go to the Netherlands to help and support the Dutch States General. He is however loath to conduct warfare against one of your Majesty’s servants (which could be the case if the rumours that the Duke of Guise intends to rally to the side of Don Juan d’Austria prove to be substantiated.) Should honour demand that it so be, there will be no change in the good will that he feels for, nor in his desire to serve, your Majesty.

There we can see that, in order to prevent a Catholic alliance between France and Spain, Oxford was prepared to go to war against Don Juan d’Austria, the newly appointed, Spanish Governor to the Netherlands, and the Catholic Henri de Lorraine, Duke of Guise.

The historian, John Bossy (and the mindless sheep who followed his theories without giving a thought to the absurdity of them) maintained, as bold as brass: “Oxford offered to provide five ships to help in the war against the Protestants in the Netherlands, but the treaty of Bergerac rendered the offer superfluous”.

The Earl regarded the sordid business of financial speculation with aristocratic disdain. He writes to Lord Burghley from Siena: “I have no help but of mine own, and mine is made to serve me, and myself not mine.”

He did however succumb to the temptation of investing in an expedition that was led by his friend Martin Frobisher (1535–1594). At the end of May 1578 Frobisher set off for the Polar Sea with 350 men in 16 ships.

The purpose of the expedition was the discovery of the Northwest Passage to China. The sea route via an American “North Cape” would have opened a new trade route to the East Indies, much to the detriment of Spain. Furthermore, there was hope of finding gold. (Frobisher had brought samples back with him from his first two expeditions and they were thought to contain gold.) The personal goals of Martin Frobisher were to complete the cartography of the world and to conquer the Arctic, or as Frobisher was wont to call it: “Meta incognita” (the unknown boundary).

The expedition was financed by Queen Elizabeth, Lord Burghley, the Earls of Leicester, Warwick, Sussex, Hunsdon, Pembroke, Sir Thomas Gresham, Philip Sidney, Edward Dyer, John Dee and many others invested into the enterprise of the China Company (Company of Cathay), but with £1000 Edward de Vere was the main investor. Not only did he invest money, he also contributed these illustrious lines:

To my very loving friends William Pelham & Thomas Randolph, esquires, Mr Young, Mr Lok, Mr Hogan, Mr Field, & others the Commissioners for the voyage to Meta incognita.

After my very hearty commendations, understanding of the wise proceeding & orderly dealing for the continuing of the voyage for the discovery of Cathay by the northwest which this bearer, my friend Mr Frobisher, hath already very honourably attempted, and is now eftsoons to be employed for the better achieving thereof, and the rather induced as well for the great liking her Majesty hath to have the same passage discovered as also for the special good favour I bear to Mr Frobisher, to offer unto you to be an adventurer therein for the sum of one thousand pounds or more if you like to admit thereof, which sum or sums, upon your certificate of admittance, I will enter into bond shall be paid for that use unto you upon Michaelmas day next coming.

Requesting your answers therein, I bid you heartily farewell.

From the court, the 21 of May, 1578.

Your loving friend, Edward Oxenford

Three weeks after he set sail Frobisher and his fleet arrived in Greenland. He declared this cold paradise to be the property of the English crown and gave it the name of “West-England”. Shortly after they encountered a terrible storm, losing a ship with its cargo of timber for the winter quarters. A blizzard caused Frobisher to lose his way and for twenty long days they sailed along “the mistaken strait” – the Hudson Bay. When they finally got back to the open sea there was a serious threat of mutiny; the crew didn’t want to sail any further north in the damaged ships.

Martin Frobisher

Frobisher landed in “his” bay gave the order to load a thousand barrels of what he assumed to be gold ore to be stored on the ships. When the fleet arrived back in England, the “gold” turned out to be iron pyrite (“fools gold”) and the noble speculators lost any hope of seeing there money again.

In 1576, the author Edward de Vere had published some poems, under his own name, in a poetical anthology: The Paradise of Daintie Devices. He signed the innovative laments and songs, either with the code “E.O.” (Earl of Oxford) or with the pseudonym “My lucke is losse”: the English variation of “Master Fortunatus Infoelix” (the fortunate unhappy from Twelfth Night). In the years thereafter, no further works were published under the name of the Earl, or at least, nothing that he gave into commission himself.

A letter from Gilbert Talbot (later Earl of Shrewsbury) to his father, dated 5 March 1579, bears witness to the activities of Edward de Vere, the actor.

It is but vain to trouble your Lordship with such shows as were showed before Her Majesty this Shrovetide [1 – 3 March 1579] at night. The chiefest was a device presented by the persons of the Earl of Oxford, the Earl of Surrey [Philip Howard], the Lords Thomas Howard and [Frederick Baron] Windsor. The device was prettier than it happened to have been performed; but the best of it, and I think the best liked, was two rich jewels which were presented to Her Majesty by the two Earls.

Strange though it may seem, there are no longer any copies in existence of the comedies which, as confirmed by documentation from contemporaries, Oxford wrote specially for Elizabeth’s court. (Nobody really knows what to make of the “Historie of Error” which is mentioned in the Revel’s account of 1577.)

In the period of time between 1578 and 1585 the courtier Humphrey Coningsby (c. 1567–c. 1610), a collector of courtly lyrics wrote down, by hand, fourteen new poems from Oxford – among others, “My mind to me a kingdom is” – and the beautiful “Echo verses” to Miss Anne Vavasour:

Sitting alone upon my thought in melancholy mood,

In sight of sea, and at my back an ancient hoary wood,

I saw a fair young lady come, her secret fears to wail,

Clad all in colour of a nun, and covered with a veil;

Yet (for the day was calm and clear) I might discern her face,

As one might see a damask rose hid under crystal glass.

Three times, with her soft hand, full hard on her left side she knocks,

And sigh’d so sore as might have mov’d some pity in the rocks;

From sighs and shedding amber tears into sweet song she brake,

When thus the echo answered her to every word she spake:

Oh heavens ! who was the first that bred in me this fever? Vere

Who was the first that gave the wound whose fear I wear for ever? Vere.

What tyrant, Cupid, to my harm usurps thy golden quiver? Vere.

What sight first caught this heart and can from bondage it deliver? Vere.

Yet who doth most adore this sight, oh hollow caves tell true? You.

What nymph deserves his liking best, yet doth in sorrow rue? You.

What makes him not reward good will with some reward or ruth? Youth.

What makes him show besides his birth, such pride and such untruth? Youth.

May I his favour match with love, if he my love will try? Ay.

May I requite his birth with faith? Then faithful will I die? Ay.

And I, that knew this lady well,

Said, Lord how great a miracle,

To her how Echo told the truth,

As true as Phoebus’ oracle.

Mistress Anne Vavasour

Either in the summer or the autumn of 1579 Edward de Vere fell in love with Anne Vavasour. She was eighteen or nineteen years old, she had black hair and she was beautiful. However, She was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth. With the first kiss of this forbidden love he had plucked the rose so jealously guarded by the Virgin Queen. It was as if a mortal were to court one of the symbols of purity, the companions of the goddess Diana. The ladies-in-waiting were recruited from the highest families in the realm and in return for services rendered they were prepared for marriage to high-ranking husbands. Needless to say, the Queen vouched for the virginity of her charges. A married man, who deflowered a girl whose innocence was guaranteed by this proud and spirited Monarch – and the girl herself – were indeed playing with fire.

It was imperative that their love remained a secret, the slightest gesture, an ill chosen word or a fond glance could have betrayed them. They had to enact that which the depths of their souls spurned, their disguises had to be as impenetrable as the thickest castle walls, not a tiny flicker of the light of truth could be allowed to escape the masks of deceit, until the enacted lie and the forbidden truth lay side by side as twins.

At this time, between 11 and 29 August 1579, at the time during the visit of Hercule-François Duke of Alençon to Whitehall Palace to court, the beautiful, though somewhat mature Queen, a chance meeting, between the two most gifted poets at court, took place.

The twenty nine year old Earl of Oxford, author of “devices” and comedies, and the twenty five year old Philip Sidney (1554–1586), author of the romance Arcadia, almost allowed an argument, over whose turn it was to play, turn into a duel to the death; fortunately, the duel did not take place. It is important to consider at this point that Oxford was in favour of the “French marriage” to “Monsieur” while Sidney was an opponent of it. The Earl demanded that the lower ranking Sidney should let him play first.

Sidney answered provokingly, whereupon Oxford grew angry and, before the onlooking French marriage-commissioners, denounced him by the name of “Puppy”. Sidney asked him to repeat it, and he did, this time more loudly, upon which Sidney gave him the lie direct (“puppies are gotten by dogs and children by men”). Then, after a moment’s silence, Sidney and his friends strode from the court. Having waited a day in vain for Oxford’s challenge, Sidney sent the Earl a reminder of honour’s obligations, and Oxford, thus jostled, responded in honour. The Privy Council, however, had caught wind of the matter and informed the Queen of it. Elizabeth in turn took young Sidney aside and explained to him “how the gentleman’s neglect of the nobility taught the peasant to insult upon both”. She made it clear that the difference in rank made a duel inappropriate. Sidney bowed to her decision. (See: Dwight Peck, 1978)

|

|

|

| (Sir) Philip Sidney | Tennis Court |

The quarrel rekindled in 1580 when Sidney wrote a letter to Queen Elizabeth, trying to dissuade her from the “French marriage”. Again the Queen intervened and calmed the two men down. The Earl was told to remain in his room for two weeks and Sidney was sent away from court for an undetermined period of time.

A most dramatic incident occurred shortly before the Christmas of 1580. Oxford accused his two former friends Lord Henry Howard and Charles Arundell of a Catholic conspiracy against the crown. It turned out that the two men were traitors; they had deliberately stirred up ill feeling against Elizabeth whilst praising the glories of Spain.

Lord Henry Howard, later to be the Earl of Northampton, (1540–1614) was highly intelligent and cynical. However, he was also an insidious woman hater. He was the brother of the convicted traitor, the Duke of Norfolk, and he made no secret of his catholic faith. When in danger of being drawn into the wake of Norfolk’s demise after his plot against the crown, Henry Howard cunningly lied his way out of the matter.

Lord Henry Howard

In 1583 Lord “Harry” was thought to be connected with a plot to murder Queen Elizabeth, (the Throckmorton Plot), though nothing could be proven. After having ruined all his chances with Queen Elizabeth he set about ingratiating himself with King James VI of Scotland (latter James I of England), obviously the correct tactic; under the patronage of James I, Howard was raised tremendously in rank and privilege. (Partly on the basis of Howard’s evidence, Sir Walter Raleigh was imprisoned in the Tower of London for 13 years; to advance his own interests, he supported the divorce of his great-niece from her husband. Later he had poisoned an adversary of the divorce.)

Sir Charles Arundell (1539–1587) was related to both Henry Howard and Edward de Vere. Along with Henry Howard, he supported “The French marriage” and he dreamt of Phillip II of Spain’s domination of the entire world. His reaction to Edward de Vere’s accusation (partly intended as a defence, partly revenge) was to write endless tirades against the Earl. When the Throckmorton plot was discovered in 1583, he fled to France where, still working for the Spaniards, he concentrated his efforts on trying to damage the reputation of the Earl of Leicester.

On the strength of Oxford’s accusation Howard and Arundell were arrested and interrogated for months. In an attempt to discredit the Earl, Sieur de la Mauvissière (a friend of Mary Stuart) sent a report that was full of inconsistencies to King Henri III, in which he described Oxford as being a fallen catholic. Lord Howard responded to the charges of treason by saying that his accuser was an unbalanced malevolent wastrel. Arundell filled an accusation on 9 counts, and 70 sub-counts, including atheism perjury and murder. As I brought to attention in 2009, the historians Bossy (in 1959) and later Nelson (in 2003) along with their flock of sheep, took the accusations of the ingenious liar, Mauvissière along with the blatant libel of Howard and Arundell, copied it parrot style and made it the foundation of wild, ridiculous theories.

Queen Elizabeth was unmoved by the hysterical accusations of the two Catholics. Oxford was not subject to an interrogation, on the contrary, she invited him to take part in the New Year’s festivities at court where she graciously accepted his gift: “A fair jewel of gold, being a beast of opals with a fair lozenged diamond, three great pearls pendant, fully garnished with small rubies, diamonds, and small pearls, one horn lacking”. Furthermore she expected his participation in a tournament that was to be held in honour of Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey on 22 January 1581.

The poetic Earl, or: “The Knight of the Sun-Tree” harvested admiration and prizes at this tournament. After he had “valiantly broken all the twelve staves” he received the first prize from the hand of the Queen herself. This glorious triumph collapsed into disgrace and demise, just two short months later. Anne Vavasour became the mother of a son on 21 March 1581 and gave him the name of Edward.

The Queen was absolutely livid, she regarded Oxford’s secret love affair as a blow to her own personal honour. Not only was Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen, responsible for the purity of her virginal elite, it was also her responsibility to ensure that no inappropriate alliances should germinate in her court. She gave the order that both adulterers be thrown in the Tower without hesitation. – Oxford tried to flee the country but he was caught before he could board a ship. He and Vasavour remained in prison until 8 July 1581, after his release he was placed under house arrest.

On 12 July 1581 Sir Walsingham wrote to Lord Burghley: “Her Majesty is resolved (upon some persuasion used) not to restore the Earl of Oxford to his full liberty before he hath been dealt withal for his wife.” In compliance with the Queen’s orders, and with regard to the fact, in hindsight, that the information, concerning the alleged infidelity that caused their separation after his return from Italy, came from the mouth of the lying traitor Henry Howard; the Earl and Anne Cecil were reunited after seven years.

The Queen restored the Earl’s freedom and as a token of reconciliation, she made him a present of a hat, "fashioned in the Dutch style, of black taffeta with band enbrodered with a shipe [reward] of pearl and gold.“ (See, Janet Arnold, Lost from her Majesties Back, London 1980).

All the same, for the following two years he was a persona non grata at court. He was not invited to any royal functions and he was left defenceless against the accusations of his enemies Howard and Arundell.

Master Thomas Knyvet, demanded satisfaction on behalf of his dishonoured niece, Mistress Vavasour. As unfortunately, Knyvet was also related to Howard and Arundell. The two noblemen, both of them accompanied by about twelve armed men, met to fight a duel on 3 March 1582. The duel escalated to a free for all. Boats people from a near-by ferry tried to intervene with shouting, poles and boat hooks. At the end of the conflict, Knyvet was injured, Oxford was badly injured and one of Oxford’s men was dead.

In May 1583 Oxford received unexpected support from an old rival, a man who had risen to fame as a military commander, as a courtier and latter as a voyager to America, Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552–1618).

Sir Walter Raleigh

Towards the end of the fifteen seventies Raleigh had sent a poem to Anne Vavasour warning her about the Earl:

Many desire, but few or none deserve

To cut the corn not subject to the sickle;

Therefore take heed, let fancy never swerve,

But constant stand, for mowers minds are fickle;

For this be sure, the crop once being obtain’d

Farewell the rest, the soil will be disdained.

Lord Burghley, who was concerned about Oxfords continuing banishment from court after his fall from grace, asked Walter Raleigh to intervene. Feeling flattered by this interest in his person from such high places, Raleigh packed the bull by the horns and went straight to Queen Elizabeth. He warned against ordering a confrontation between Lord Howard and the Earl and against allowing events that could be dangerous for the Earl: “and therefore it were to small purpose, after so long absence and so many disgraces, to call his honour and name again in question”. Elizabeth declared that she had merely wished to teach Oxford a lesson and that she would, in her generosity, “remit the punishment of his offences”.

(Eight years later, after the discovery of Raleigh’s secret marriage to Elizabeth Throckmorton, the Queen locked up her favourite for two months and banned him from court for a further five years.)

During a visit at Theobalds Castle in May 1583, Elizabeth graciously reinstated Oxford. Sir Roger Manners wrote to his nephew on 2 June 1583: “my Lord of Oxford came to her presence, and after some bitter words and speeches, in the end all sins are forgiven and he may repair to the court at his pleasure. Mr Raleigh was a great mean herein, whereat Pondus is angry for that he could not do so much.”

In the meantime Lord Walsingham’s secret service had managed to gather information concerning Henry Howard’s activities in the catholic underground movement. His source is an Italian spy – the man who celebrates the catholic mass in the French embassy, home of Mauvissière, his host. This spy (as shown by Bossy in 1991) is the philosopher and former Dominican friar Giordano Bruno, alias “Henry Fagot”. Fagot wrote at the end of May 1583: “Queen Mary’s most important agents are Master Throckmorton and Lord Henry Howard. They only bring things from her, or collect things for her, under cover of night”.

After the discovery of the “Throckmorton Plot” in November 1583 the Earl of Oxford was completely reinstated. Throckmorton was executed, Sir Charles Arundell fled to France while Henry Howard (the brother of the beheaded Duke of Norton) got off with six month in jail.

See: Kurt Kreiler, Anonymous SHAKE-SPEARE, The Man Behind. E-Book 2011