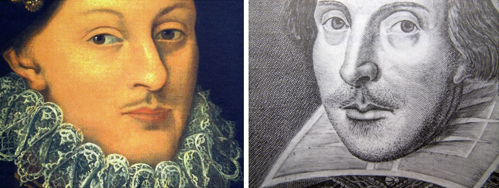

4.2. Biography II

To recapitulate:

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was born on 12 April 1550, (according to the old calendar), his family belonged to England’s oldest and most established nobility: his ancestor Aubrey de Vere fought at the side of William the Conqueror in the eleventh century. Edward de Vere was twelve years old when his father died; and his mother remarried shortly thereafter. The young Earl was declared a ward of court and sent to live with his new foster father William Cecil, Lord Burghley (the man was to become his father-in-law), the Queen’s most trusted advisor and the most powerful man in the country. Under the auspices of such outstanding teachers like Sir Thomas Smith, Lawrence Nowell and his uncle Arthur Golding, Edward de Vere studied Latin, French, Italian and cosmography. He also studied dance and the various disciplines involved in jousting tournaments.

He matriculated at the age of eight and at sixteen obtained his “Master of Arts”; subsequently he started studying law at Gray’s Inn. At the age of seventeen he assisted his uncle Arthur Golding with the translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. During a fencing bout he inflicted a mortal wound on Thomas Brincknell, a member of the kitchen staff. Just reaching twenty, he accompanied the Earl of Sussex on a military campaign to Scotland and one year later he married Lord Burghley’s fourteen year old daughter, Anne Cecil.

In August 1572, he staged a mock battle at Warwick Castle for the entertainment of Queen Elizabeth and became a patron of the arts. In 1573 he published A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres together with George Gascoigne, the publication that served as a vector for The Adventures of Master F. I. written under the pseudonym “Fortunatus Infoelix”.

In 1575, Oxford travelled through France and Germany to Italy – to return end March 1576. During his travels his wife had given birth to his child. On the grounds of reports of infidelity he had received he broke off any relationship with her.

He wrote his first tragedy: Titus and Andronicus before he went to Italy. In the years between 1576 and 1584 he wrote the Italian plays: The two Gentlemen of Verona, Twelfth Night, The Comedy of Errors, The Taming of the Shrew, Much ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice and a comedy about Elizabeth’s “French marriage”: Love’s Labour’s Lost.

In 1580, the rhetor and traditionalist, Gabriel Harvey writes a caustic satire on Oxford, Edmund Spenser calls him “the perfect pattern of a poet”, but he advises him to stick to heroic sagas and not write comedy.

Towards the end of 1580, Oxford severs all relationship with his catholic friend and cousin, Lord Henry Howard. He has an affair with Anne Vavasour, one of Elizabeth’s ladies-in-waiting and gets her pregnant. Queen Elizabeth is infuriated at the seduction of her lady-in-waiting and commits both lovers to the Tower. It is not until May 1583 that Oxford is re-allowed to the court. At the end of 1581, the poet returns to his wife and child. On 3 March 1582 he fights a duel against an uncle of Anne Vavasour, in which he is wounded.

Elizabeth in procession to Blackfriars

On 17 November 1584, the man whose “countenance was shaking spears” (see p. 118) took part in his last tournament. Obviously, the wound that he had incurred in the duel, had recovered enough for him to partake in this most royal sport. With his participation in the tournament to celebrate Queen Elizabeth’s twentysixth jubilee The Earl of Oxenford signals his official comeback.

Lupold von Wedel, a German observer comments on the richly adorned combatants: “The costs amounted to several thousand pounds each”. – An enormous expenditure for a man who was rapidly approaching bankruptcy.

Queen Elizabeth then made a very unexpected decision. She dispatched the poet and courtier, Edward de Vere to the civil war in The Netherlands along with the experienced military campaigner, Sir John Norris. Oxford is appointed General of the Horse.

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

On 27 August 1585 (continental calendar) Oxford’s 2000 men strong company lands in Vlissingen. Antwerp had been forced to surrender after a year long siege by the Spaniards, just ten days previously. A further 4000 English soldiers followed in September. They brought the news with them that Sir Philip Sidney would be coming to The Netherlands along with his uncle, the Earl of Leicester, who was to take over the political and military command. It was beneath the aristocratic dignity of the Lord Great Chamberlain to serve under the autocratic Earl of Leicester; so he went back home to England on 21 October 1585. In 1586 Sir Philip Sidney died of an injury that he incurred in The Netherlands.

Oxford’s tragedy Prince Hamlet was probably written in 1585/86. Although Shakespeare stays close to Belleforest’s translation of Saxo Grammaticus (12th century) there are similarities, that the audience at court must have noticed, between the character Polonius, “the fishmonger” and the real life person, Lord Burgley (= “Pondus”).

1586 didn’t bring victory in the Netherlands but it did bring a dramatic development in the relations between the Queen of England and the Queen of Scots. Mary Stuart had managed to resume her secret correspondence with foreign governments and sympathisers in England.

Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland

However, Walsingham’s secret service managed to turn things round. The letters, hidden in beer (or wine) barrels all went over the desk of a certain Thomas Phelippes, a small blond pock-marked man who was a master of the art of decoding. After a group of young conspirators came together under the leadership of the nobleman Anthony Babington, with the declared aim to murder Queen Elizabeth, Mary Stuart welcomed the plan wholeheartedly; she also offered good advice for its success. Phelippes decoded the letter and sent a copy to Walsingham. The reverse side of the envelope bore the symbol for urgency: The gallows!

The same year saw Oxford’s financial situation deteriorated to an unprecedented level. He went, to Hampton Court personally to give more weight to his petition for financial support from the crown. The hereditary title of “Lord Great Chamberlain” didn’t automatically qualify him for a state salary. He served her majesty in different ways. He supervised the English acting ensembles and wrote immortal plays that were performed at court, needless to say without financial rewards, as is fitting for an aristocrat. However, now that his inheritance was spent, her majesty had to be reminded, in the politest possible way, that art was also a service deserving of financial reward.

On 26 June 1586 Queen Elizabeth determined that Oxford should receive the sum of ₤1000 per annum, payable in four instalments. The instructions for the payments “unto Our right trusty and well beloved Cousin the Earl of Oxford” didn’t offer any explanation as to why the payments should be made, only that they must be made. Efforts to secure a more lucrative source of income, such as a trading monopoly, on Oxford’s part proved to be of no avail. Up to his death, he was supported by the crown to the tune of ₤1000 per annum. No more, no less.

Truth being stranger than fiction, there is a Shakespeare anecdote that describes the situation exactly, even though we find it where we least expect to do so. In the year 1662, Dr John Ward became the vicar of Stratford. Being interested in history he noted all that he could find out about the late William Shaksper in his diary. “He supplied the stage with two plays every year, and for that had an allowance so large that he spent at the rate of 1,000 pounds a year, as I have heard.”

Could it be that the thrifty Queen had made a deal with “Shakespeare”? One could speculate that Elizabeth took over the role of the theatre director and gave Shakespeare instructions concerning the subjects of his plays; the subjects with which he busied himself for the rest of his life: The history of Great Britain and its Monarchs.

The Great Chamber at Fotheringhay castle met on 12 October 1586 to reach judgement over Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland. Among the 42 members present were: The Lord Treasurer Burghley, the Lord Chancellor Christopher Hatton, the Earls of Oxford, Shrewsbury, Kent, Worcester, Viscount Montague, Lord Zouche, Lord Lumley, Sir Amias Paulet, and the two highest ranking judges in England.

Mary Stuart was found guilty of being a co-conspirator in an assassination attempt on Queen Elizabeth and was sentenced to death. Queen Elizabeth did not sign her death warrant until 1st February 1587. One week after the warrant had been signed Mary Stuart was beheaded.

After the execution of Mary Stuart Pope Sixtus V renewed Elizabeth’s excommunication and ordered that she be removed from the throne of England; he entrusted Philip II of Spain with the fulfilment of his wishes.

Furthermore, the Spanish King was neither prepared to leave Elizabeth’s military advances in the Netherlands unchallenged, nor was he willed to tolerate repeats of English state-supported piracy.

With a Spanish naval attack looking imminent, England’s most successful privateer Sir Francis Drake set out on a reconnaissance mission along the coast of Spain with a fleet of 24 ships. True to his name “el Draque” (the dragon) – he stopped by at Cadiz, destroyed the harbour, stole six galleons then, almost as an afterthought, and set fire to more than thirty Spanish ships, after which he calmly sailed back to England without any resistance.

After a further year of preparation, the Spanish Armada set sail for England, from Lisbon, on 19 May 1588 (continental 29 May, as of now I shall omit the continental date) under the command of Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia. The Armada consisted of 30,000 men in 130 ships, 64 of which were heavy galleons.

On 9 June the Armada hits a strong north-westerly storm at Cape Finisterre (Cabo de Finisterre) losing four galleons and suffering damage of other ships. Medina Sidonia ordered the fleet to dock at the harbour of La Coruña for repairs and restocking.

On 23 May 1588, the British fleet had already gathered at Plymouth harbour. Since the summer of 1587, England had been making full use of the time, to prepare its defences: England’s naval command (men like John Hawkins, Francis Drake and Martin Frobisher) felt sure that they could defeat the Spaniards at sea with the tactical deployment of artillery. In the case of a Spanish landing, 100,000 armed men were ready and waiting for them on the shores of England.

Queen Elizabeth had entrusted the command over the navy to Lord Charles Howard, Earl of Nottingham. The position of Vice Admiral was entrusted to the legendary Sir Francis Drake. The English fleet was made up of 34 new, highly manoeuvrable, newly built warships, each between 600 and 800 tons, along with 106 privateer ships and merchant vessels, converted to warships. Fifty smaller ships maintained supplies for the 15.000 strong fleet.

Edward de Vere’s participation in England’s defence against the Spanisch Armada is documented by three reliable contemporary witnesses, the chroniclers John Stowe and William Camden, also the author Richard Hakluyt in his book The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589).

Camden names the Earl as being one of the first to finance his own ship with which to come to the aid of the British Navy. This means that the Lord Great Chamberlain was one of those eager warriors who, as of 23 May, were waiting off the shores of Plymouth, to fight the Spanish. Oxford had always dreamt of performing a heroic act, for his Queen and country instead of just writing about them. It looked as his dream was to come true, but as is often the lot of dreamers, things turned out differently.

While the English fleet was waiting, the Spanish fleet hit bad weather. For two weeks the English, who knew nothing of the cause of the delay were expecting battle to commence at any second. During this nerve racking wait, Oxford received news that his wife had died of a fever in Queen’s Court, Greenwich.

In the Latin and the English obituaries that the grief stricken Lord Burghley enters in to the state archives, his daughter is compared to the virtuous Penelope, the wife of Ulysses, or the patient Griseldis (a woman famed for being wrongfully cast out by her husband). A woman to whom life had sent many trials and who had no fear of death.

The funeral of Anne Cecil, Countess of Oxford took place in Westminster Abbey. It would appear that only a few men were in attendance. Neither Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, nor William Cecil, Lord Burghley, nor the brother of the deceased were mentioned in the report on the funeral by William Dethick, Garter Principal King of Arms, wherein the sixty year old Countess of Lincoln (a friend of the Queen) is mentioned as “chief mourner”. William Cecil was, in all likelihood, impeded by illness, whereas it’s safe to assume that Oxford and his brothers in law, Thomas and Robert Cecil remained in Plymouth.

On hearing that the Spaniards had been delivered such a blow by the weather, both Charles Howard and Francis Drake pleaded for following them back to Spain and attacking them in their own harbours. 90 English ships set off for Spain on 24 June 1588, but bad weather forced them to turn back. A repeat of the same plan was attempted on 12 July 1588 – but five days later, all of the ships were back in Plymouth.

We know that the Earl of Oxford took part in these attempts to destroy the Spanish war ships because his name was mentioned in the ensuing victory hymn, albeit with flowery words.

De Vere whose fame and loyalty hath pierced

The Tuscan clime, and through the Belgike lands

By winged Fame for valour is rehearsed,

Like warlike Mars upon the hatches stands.

His tusked boar ‘gan foam for inward ire,

While Pallas filled his breast with warlike fire.

On 12 July 1588, the Spaniards set sail from La Coruña; a week later they were sighted off the coast of the Isles of Scilly. In this very week, probably at Burghley’s request, Edward de Vere returns to London. When the Armada reaches Plymouth the English fleet have difficulty leaving the harbour because of unfavourable winds. This was Spain’s big chance; they could have attacked and forced the very close-quarters battle on to the English for which the Spaniards were so well prepared. However commander Medina Sidonia had received strict instructions from King Philip II not to engage the English in combat before they reach Dunkirk. The Duke of Parma and his army were to be picked up in Dunkirk and from there they were to go to the mouth of the river Thames. Should this invasion army have landed, England would have indeed been in serious trouble. After the Armada sailed past the vulnerable English fleet, the English followed them, doing what they did best, firing at the Armada with the superior English cannons and then turning around before the Spaniards could even get them within range of their less efficient artillery.

By the time the Spaniards had reached Calais they had been under serious artillery fire for a week and two of their ships had been captured. On 27 of July the Armada anchored between Calais and Gravelingen. One could even see the huge galleons from England.

After the Armada had sailed past Plymouth and Portsmouth, Oxford came back to the war theatre. On either 25 or 26 July he sailed – via Tilbury – down the Thames where he re-joined the English fleet. At this point, we assume that he spoke with Lord Admiral Howard. After which he sailed back up the Thames to London via Tilbury. On 28 July 1588 the commander of the military post in Tilbury, the Earl of Leicester wrote the following letter to Sir Francis Walsingham. Unfortunately, this somewhat confusing letter is the only official account of the Earl of Oxford’s contribution to the defeat of the Armada:

my Lord of Oxford was with me [26 July ?] as he went [to Admiral Lord Howard], and returned again yesterday [27 July] by me with Captain Huntley in his company. he seemed only his voyage was to have gone to my lord Admiral, and at his return seemed also to return again hither to me this day [28 July] from London whither he went yesterday for his armour and furniture. if he come I would know from you what I shal do. I trust he be free to go to the enemy for he seems most willing to hazard his life in this quarrel.

Perhaps Oxford was in charge of communications between the naval command and London. But why should this task fall to Oxford? Did he just wish to inform himself of the situation in London? The reason that Leicester offered for his return to London seems hardly likely.

All we know is that the Earl wanted to fight but that circumstances crossed his intent. Whatever the reason, the main battle was on 29 July and the Earl of Oxford missed it. Shortly after midnight, the English sent their deadly fire-ships (“Vulcanos”) using the tidal currents, amidst the closely anchored Spanish ships. These fire-ships, filled with tar and gunpowder caused panic among the Spaniards. Many ships cut through the anchor ropes before the ships were under sail. In such a situation ships do not react to the rudder and can’t be steered. Some ships drifted onto sandbanks or drifted into the open sea, some bumped into each other, while others caught fire.

The next morning at dawn, after the Spanish fleet had re-grouped, the decisive battle commenced. Because of their position, the direction of the wind and the manoeuvrability of their ships, the English had a clear advantage. Moreover, the Spaniards had all but run out of ammunition. It was an easy matter for the English and the Dutch to separate Spanish ships from the fleet and inflict serious damage firing their cannon balls at the waterline of their unfortunate victims. Soon there was no Armada any more, just a collection of disorganized, separated, harmless vessels struggling for their very existence. As soon as the wind changed from northwest to southwest, Medina broke off hostilities and set off in a northerly direction, with the English close behind him, his intention being to sail the long way around Scotland and back to Spain.

Oxford arrived back at Tilbury on 28 July or 29 July. Leicester wanted to put him in command of Harwich harbour, a small habour but of potential importance as the last deep-water harbour north east of London that the Spaniards could have entered. On hearing of the desolate state of the Armada Oxford refused the offer.

Leicester wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham from Tilsbury on 1 August 1588:

I did as her majesty liked well of deliver to my Lord of Oxford her gracious consent of his willingness to serve her. And for that he was content to serve her among the foremost as he seemed, she was pleased that he should have the government of Harwich and all those that are appointed to attend that place which should be 2000 men. A place of trust and of great danger. My Lord seemes at the first to like well of it, afterwards he came to me and told me he tought that place of no service nor credit, and therefore he would to the court and understand her majesties further pleasure, to which I would not be against; but I must desire you as I know her majesty will, also make him know that it was of good grace to appoint that place to him having no more experience than he hath, and then to use the matter as you shall think good. for my own part being glader to be rid of him than to have him, but only to have him contented. which now I find will be harder than I took it, and denyeth all his former offers he made to serve, rather than not to be seen to be imployed at this time, and I pray you inform her majesty hereof that she may give him an answer as is fit.

Leicester closes his letter with the angry words:

I am glad I am rid of my Lord Oxford, seeing he refuseth this and I pray you let me not be pressed anymore for him what suit so he ever make.

Leicester and Oxford were as incompatible as boar and bear, as fox and falcon. However, at the victory celebrations, in November, all rivalry was forgotten. To the Queen’s great sorrow, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester died in September 1588, probably of some stomach disease.

The nation celebrated its resounding victory over Spain, but Oxford had missed his cue. Ill winds and his own restless, impulsive nature had robbed him of his laurel leaves. While the victory bells were ringing around him, the poet may well have taken stock of his life: His wife was dead; he had three daughters, but no male heir. He had become a rich beggar, dependent on handouts from Queen Elizabeth. A man without any influence, no adulation for heroic acts apart from those on stage, and even they were only known to a few.

Mildred Cooke, Baroness Burghley, followed her daughter to the grave in April 1589. Lord Burghley erected a monument for both of them – the inscription for his daughter read:

Anna Countess of Oxford, daughter of William Cecil Baron of Burghley, was born 5 December 1556. She became the wife of Edward de Vere, illustrious Earl of Oxford, in the 15th year of her life. From this union she became the mother of several sons, but left behind three surviving virgin daughters: Lady Elizabeth Vere, aged 14; Lady Bridget Vere aged 5; and, third, an infant girl, Lady Susan. This Anna lived ever a modest maiden and a chaste wife, faithful in her love, a daughter wonderfully devoted to her parents in all exigencies, exceedingly diligent and devout in her devotion to God. Debiliated by a burning fever, in the hope of the power of heaven, she gave up her soul along with her spirit with most earnest prayers to God as her creator and redeemer, on 5 June 1588 in the palace of Queen Elizabeth at Greenwich.

Lord Burghley didn’t miss the opportunity to mention his three granddaughters and to mention himself as their “most loving grandfather, who hath the care of all these children, so that they may not be deprived either of a pious education or of a suitable upbringing.” In other words: “Their father is unreliable, but at least their grandfather can provide for their needs.”

Two years after the death of his daughter, Anne, the Lord High Treasurer sets about the task of finding a suitable husband for his eldest granddaughter, Elizabeth de Vere. In the summer of 1590, just before Elizabeth de Vere’s fifteenth birthday, Burghley found the right man, or so he thought. The chosen suitor was Burghley’s rich ward, Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton who was almost seventeen at the time.

Wriothesley was born on 6 October 1573. His father was the second Earl of Southampton (1545–1581), a devout Catholic. His mother was Mary Brown, daughter of the first Viscount Montague. As a child he lived in Sussex, not far from the south coast of England. His parents broke up when he was six years old. His ill-tempered, stubborn, yet none the less, weak father banished his mother from the family home because he suspected her of committing adultery. The child shared his father’s suspicions. In 1581 his father died and Henry Wriothesly, third Earl of Southampton moved into Cecil House, as a ward of the crown. At the age of twelve he took up studies in St John’s College in Cambridge, where he got to know the nineteen year old Thomas Nashe. In 1589 he graduated from Cambridge and joined “The Honourable Society of Gray’s Inn”, a professional association for barristers and judges.

The plan would have been perfect if not for the fact that the young Earl of Southampton didn’t want to get married, at least not yet and not to Elizabeth de Vere. He made excuses, he hid behind his mother, he said he was too young and asked to have the matter postponed for a year. We can safely assume that the Earl of Oxford was also eager to have his daughter marry such a good match and that is why he wanted to make the union interesting for Wriothesely.

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton

If we think the matter through, logically, then we can see that this is how the first seventeen sonnets from william shake-speare, dedicated to the youth, came into being.

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak’st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

The poet was now forty yeas old and a widower. In the hope of winning him over as a son in law, the financially ruined Lord Great Chamberlain sent seventeen sonnets to the seventeen year old Henry Wriothesely without getting him one step closer change his mind. A life cycle, beauty and love formed itself. An older man sees, in a youth, the mirror image of himself, when he was young. He wants the youth to make love, to reproduce, not just with some woman but with his own daughter, his own flesh and blood.

When these sonnets fail to work, the father of three daughters and an illegitimate son falls in love with his beautiful would be son in law.

The incessant demand that the man should marry and found a family would seem to be inconsistent ... with a real homosexual passion. It is not even very obviously consistent with normal friendship. It is indeed hard to think of any real situation in which it would be natural. What man in the whole world, except a father or potential father-in-law, cares whether any other man gets married? (C. S. Lewis: English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, 1954, p. 503)

We know that the 365 sonnets from Francesco Petrach provided the material for this book of hours, on love and death. However Wriothesly was to Oxford what Laura was to the Italian poeta laureatus. Petrarch observed and described both human and the godly qualities in Laura. The fact that she was unattainable in her godliness was also a source of rapture to the poet. Shakespeare’s love for the youth has a poetic dimension, this makes him the sixteenth century answer to Petrarch, however the sharp, analytical observations and the subjective power of self expression go way beyond the norms of the early Renaissance.

The poet wants nothing more than to recognize himself in the young man, rediscover, admire, immortalize and love himself. Oxford regards the youth as a picture of his own hopes, inspirations and passionate wishes.

20

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou the master mistress of my passion,

A woman’s gentle heart but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women’s fashion,

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling:

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth,

A man in hue all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created,

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

Shake-speare’s 152 sonnets (the 126 sonnets to the youth and the 26 sonnets to the “Dark Lady”) betray even more about the passions and the obsessions of the Earl of Oxford.

The youth with the rose like name (Wriothesley, pronounced “Rosely”), stimulated by the love of the poet, developes feeling for the woman to whom Skakespeare refers as “The Dark Lady” in sonnet 26. – As of 1591, the Earl was not alone. His love’s name was Lady Elizabeth Trentham, she was approximately 28 years old, the daughter of a rich landed aristocrat in Staffordshire – and she was a highly valued member of the court of Queen Elizabeth. In the beginning of July 1591, Oxford named her brother, Francis Trentham as trustee for the large piece of development land, Christ Church Garden, with instructions that the trust go to his “widow” in the event of Oxford’s death. The wedding took place late in the year of 1591 (either November or December). Elizabeth Trentham joined her fate to that of England’s impoverished Great Chamberlain. For his part, Oxford was out of financial difficulty. His new brother in law, Francis Trentham, supervised the family’s finances (including those of Oxford). He also invested ₤10,000 of his own money in the project. There was a stipulation that in the event of Oxford dying without a male heir, his fortune should go to the Trentham family.

In sonnet 34 (to the youth) the poet complains about the new situation.

Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day,

And make me travel forth without my cloak,

To let base clouds o’ertake me in my way,

Hiding thy brav’ry in their rotten smoke?

In sonnets 40–42 the whole truth comes to light:

Then if for my love, thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee, for my love thou usest,

But yet be blamed, if thou thy self deceivest

By wilful taste of what thy self refusest. (40)

Ay me, but yet thou mightst my seat forbear,

And chide thy beauty, and thy straying youth,

Who lead thee in their riot even there

Where thou art forced to break a twofold truth: (41)

That thou hast her it is not all my grief,

And yet it may be said I loved her dearly,

That she hath thee is of my wailing chief,

A loss in love that touches me more nearly.

Loving offenders thus I will excuse ye,

Thou dost love her, because thou know’st I love her,

And for my sake even so doth she abuse me,

Suff’ring my friend for my sake to approve her. (42)

There are obvious similarities between this lyrical documentation and the sonnets 127–152, which are written for the woman in the poet’s life. “The Dark Lady” has, as well could be expected, alabaster skin. She is dispirited because this old view of perfection is no longer in fashion, but though her skin is white, her hair and her soul are black. – Sonnet 133:

Beshrew that heart that makes my heart to groan

For that deep wound it gives my friend and me;

Is’t not enough to torture me alone,

But slave to slavery my sweet’st friend must be?

Me from my self thy cruel eye hath taken,

And my next self thou harder hast engrossed,

Of him, my self, and thee I am forsaken,

A torment thrice three-fold thus to be crossed:

Prison my heart in thy steel bosom’s ward,

But then my friend’s heart let my poor heart bail,

Whoe’er keeps me, let my heart be his guard,

Thou canst not then use rigour in my jail.

And yet thou wilt, for I being pent in thee,

Perforce am thine and all that is in me.

Sonnet 134 contains one of the most amazing statements in the history of English literature:

So now I have confessed that he is thine,

And I my self am mortgaged to thy will,

My self I’ll forfeit, so that other mine,

Thou wilt restore to be my comfort still:

But thou wilt not, nor he will not be free,

For thou art covetous, and he is kind,

He learned but surety-like to write for me,

Under that bond that him as fast doth bind.

The statute of thy beauty thou wilt take,

Thou usurer that put’st forth all to use,

And sue a friend, came debtor for my sake,

So him I lose through my unkind abuse.

Him have I lost, thou hast both him and me,

He pays the whole, and yet am I not free.

In this poem, in which the wronged husband asks his wife if he can have his friend back there are no less than ten terms which we normally find in the world of finance or commercial law: “I my self am mortgaged to thy will” – “My self I’ll forfeit” – “He learned but surety-like to write for me” – “Thou usurer that put’st forth all to use” – “sue a friend” – “debtor for my sake”.

This is the story of Oxford’s life. The astonishing summary: The youth pays the debts from which the poet can’t free himself. Not just because he – Oxford – is self-tormentingly in love with the Dark Lady but because, financially, she holds him in the palm of her hand.

As Lord Burghley so meticulously worked out; on 30 June 1591 Oxford owed the crown ₤11,000. (This was the old bill from from the “Court of Wards” along with fines for delayed payment and interest – three times the amount of the original bill). This debt was to be paid with the ₤10,000 investment from Francis Trentham.

Hardly any wonder that Oxford paints his wife in such dark colours. A wonder that he found tender words to write her a poem, in a situation where lesser men would have reacted with morose silence. – Sonnet 136:

If thy soul check thee that I come so near,

Swear to thy blind soul that I was thy Will,

And will thy soul knows is admitted there,

Thus far for love, my love-suit sweet fulfil.

Will, will fulfil the treasure of thy love,

Ay, fill it full with wills, and my will one,

In things of great receipt with case we prove,

Among a number one is reckoned none.

Then in the number let me pass untold,

Though in thy store’s account I one must be,

For nothing hold me, so it please thee hold,

That nothing me, a something sweet to thee.

Make but my name thy love, and love that still,

And then thou lov’st me for my name is Will.

From these lines we can safely conclude that Oxford used the name “william shakespeare” in the early sixteen nineties.

Will is the lover running after the object of his desire like a little boy running after his mother, who is trying to catch a chicken (see Sonnet 143), but he is also the angry jealous lover who forgives his male friend and shuns his woman. – Sonnet 144:

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still,

The better angel is a man right fair:

The worser spirit a woman coloured ill.

Whether this act of infidelity occurred before or after the wedding is a matter that remains undisclosed. – Sonnet 152:

In loving thee thou know’st I am forsworn,

But thou art twice forsworn to me love swearing,

In act thy bed-vow broke and new faith torn,

In vowing new hate after new love bearing.

The expression “the bed vow” is most explicit. I conclude that Shakespeare had taken none other than the “Dark Lady” to be his wife and that this beautiful lady was clever enough to keep the dark secret of her identity and her amorous faux pas to herself for more than four hundred years.

The Lord Great Chamberlain moved into a very comfortable residence close to Shoreditch, called Stoke Newington, along with his wife and his books. This new comfort demanded that he face up to economic facts. It was probably on his wife’s initiative that he bombarded Lord Burghley and Sir Robert Cecil with letters and petitions. She wanted to secure the financial future of her son, the next Earl of Oxford. However, his most patient (and sometimes impatient) efforts were to no avail. Neither did the Queen give him the trade monopoly that he desired so much, nor did she return the country residence (not far from the river Lea) that was sequestered by the crown on his father’s death. Queen Elizabeth was of the firm opinion that Oxford was incorrigible in his foolhardiness when it came to financial matters and ought to be protected from himself.

On 24 February 1593 the married couple, Edward de Vere and Elizabeth Trentham, were finally blessed with the birth of the son who was to be the 18th Earl of Oxford. He was christened Henry – this name is not to be found in the genealogy of the de Vere family, suggesting that the child was named after the, then nineteen year old, Henry Wriothesly.

In the summer of 1593 Oxford dedicates his epic poem: Venus and Adonis to the youth. A poem in which the narcissistic Adonis withstands the advances of the love-goddess Venus, much to his misfortune.

Venus and Adonis is the first work to be printed under the name of “William Shakespeare” and also the first time that the name shakespeare be revealed to the public. When the author speaks of “the first heir of my invention” he is referring to the invention of this famous pseudonym.

For this publication it was imperative to use a pseudonym. Even a generation later, the English scholar John Selden (1584–1654) explains in his famous Table-Talk: “Tis ridiculous for a lord to print verses; ‘tis well enough to make them to please himself, but to make them public is foolish.”

Oxford’s choice of the pseudonym is a story in itself. The mental picture of the spear-shaker is taken from the goddess Pallas Athena who was literary born shaking a spear. The goddess came to the world out of her father Zeus’ head – in full armour. As well as being the goddess of palaces, military strategy crafts and weaving, she was foremost the guardian of art and wisdom. In her hand a spear, not as a sign of aggression but of vigilance. The Elizabethans were thoroughly familiar with the twenty-eighth Homeric Hymn: “Athena sprang quickly from the immortal head and stood before Zeus who holds the aegis, shaking a sharp spear.” What better name could there be for a warrior poet. A man who carried the Sword of State at official ceremonies. A man who loved to take part in tournaments so much that he’d spend his last penny on new armour for the joust. A man who would chase after the Spanish navy and then sit down and write a sonnet.

The Earl of Oxford was a spear-shaker like his friend George Gascoigne: “with pen to fight and sword to write a letter”. Gabriel Harvey praised the Earl in 1578: “Your countenance is shaking spears” [vultus tela vibrat]; Thomas Vicars said in 1621: “that famous poet who takes his name from shaking and spear” [qui a quassatione et hasta nomen habet]; Ben Jonson wrote in 1623: “true-filed lines / in each of which he seems to shake a lance”. – The first name “William” could well be a reference to William the Conqueror or even to the formula “Will-I-am” = I am Desire. The poet may well have been aware of the erotic connotations of the name. We can safely assume that he read the Epithalamium of Giovanni Giovano Pontano (1429–1503), telling a young man what was expected of him on his wedding night: “When the bride is overwhelmed with the heat of her desire in your passionate embraces, then is the time to attack – my friend, you must heatedly shake your spear to inflight the longed-for wound on her.” – “Telum cominus, hinc et inde vibrans, / Dum vulnus ferus interferus amatum”. (Pontani carmina, Firenze 1902, vol.2, p. 262)

The epic poem The Rape of Lucrece was entered in the Stationers’ Register on 9 May 1594. It was also dedicated to the young Earl of Southampton, Henry Wriothesley.

On Southampton’s twentyfirst birthday, it was Lord Burghley’s duty as Master of the Wards, in accordance with the law to demand that Southampton pay a fine of ₤5,000 for his refusal to marry Oxford’s daughter, Elizabeth de Vere. This fine meant financial ruin for Southampton. Shortly afterwards Southampton joined the Earl of Essex’s cicle of friends who were opponents of Burghley. In this way Henry Wriothesley drifted further and further away from his poetic friend, paragon admirer, the man who had loved him so dearly.

In the years between 1594 and 1595, The Lord Chamberlain’s Men had at least ten plays from the quill of Wiliam Shakespeare in their repertoire: Titus Andronicus – The Taming of A Shrew – The Comedy of Errors – 2Henry VI – 3Henry VI – Hamlet – Othello – The Merry Wives of Windsor – The Merchant of Venice – King Richard II.

At this time the first pirate editions (bad quartos) of stage manuscripts came in to circulation: The most lamentable Romaine tragedie of Titus Andronicus (1594), The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Famous Houses of Yorke and Lancaster [2Henry VI] (1594), A Pleasant Conceited Historie, Called the Taming of A Shrew (1594), The true tragedie of Richard Duke of York, and the death of good King Henrie the Sixth [3Henry VI] (1595), An excellent conceited tragedie of Romeo and Juliet (1597). – These publications forced the author to react. In the years between 1597 and 1604 he had published for the first time ten “good quartos” against the “bad quartos” (Richard the Second; Richard the Third; Love’s Labour’s Lost; Henry the Fourth; Romeo and Juliet; The second part of Henry the Fourth; A Midsummernight’s Dream; Much Ado About Nothing; The Most Excellent Historie of the Merchant of Venice; The Tragical History of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark).

Robert Detobel argued in 2001 that Oxford controlled his works personally. On 22 July 1598 the printer James Roberts entered The Merchant of Venice in the Stationers’ Register. With that he had secured the rights to print the work. We notice the following prohibition clause: “Provided that yt bee not printed by the said James Robertes, or anye other whatsoever without lycence first had from the Right honorable the lord Chamberlen”. Prior to 2001, this stipulation had either been overlooked or it was assumed that the under the term “Lord Chamberlain” the political office, held by George Carey 2nd Baron Hunsdon (1547–1603), was meant and not the Lord Great Chamberlain (Edward de Vere). There was, however no reason whatsoever for Lord Hunsdon to be concerned with The Merchant of Venice even if there had been problems with censorship (but there were none). As documented by Charles W. Barrell (1944), the Lord Great Chamberlain was sometimes referred to as the “Lord Chamberlain”. A comparison with similar entries shows clearly that this particular entry does not trace back to the political office of the Lord Chamberlain, but to the play’s author, the Lord Great Chamberlain.

Elizabeth de Vere

Elizabeth de Vere, eldest daughter of Edward de Vere married William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby (1561–1642) in Greenwich Palace, London on 26 January 1595.

The rich young aristocrat was the perfect son in law for Oxford. As a young man, Derby had lived in France for three years taking regularly part in tournaments, he wandered through Italy dressed as a begging monk and he defended himself with a knive against a tiger in Egypt. After the death of his older brother the man who had been absent for so long came back to England and demanded his inheritance. (Derby’s mother, Lady Margaret Clifford was heiress presumptive to the throne of England from 1578 up to her own death in 1596.)

William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby

The hitherto turbulent life of the “Earl of Oxenforde” seemed to calm down. In a letter to Lord Burghley he complains of signs of paralysis: “I will attend your Lordship as well as a lame man may at your house.” (See Shakespeare’s Sonnet 37: “So I, made lame by Fortune’s dearest spite”, and 89: “Speak of my lameness, and I straight will halt”.)

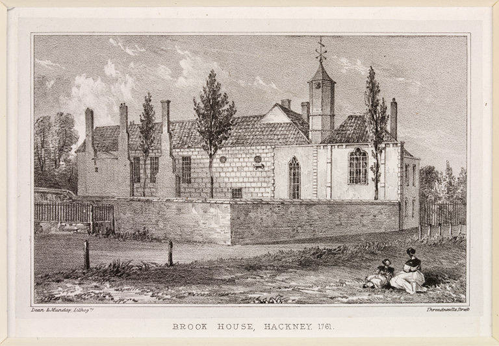

Queen Elizabeth approved the sale of King’s Place in Hackney “to our most dear cousin Elizabeth, Countess of Oxford, wife of Edward, Earl of Oxford, and to our beloved Francis Trentham”.

King’s place was an impressive stately home in north east London with gardens, farm land and orchards, amounting to 270 acres. The small palace, built at the end of the fifteenth century had once belonged to Henry VIII’s principal secretary and chief minister, Thomas Cromwell. The palace had a chapel, living and working quarters, a library and an impressive great hall. A second courtyard and a “long gallery” were added in the eighties. A contemporary description of the residence also mentions a large kitchen, pantry, buttery, wash-house, linen yard, steward’s lodge, servant’s quarters, a courtyard with a well, stables, storerooms, a distillery, a granary and a sheepfold. Beside of the ditch was a large, beautiful garden.

King’s Place, 1930

The residence was purchased by the poet and courtier, Sir Fulke Grenville (1554–1628) in 1609, who changed its name to “Brooke House”. In the middle of the eighteenth century it was converted to a lunatic asylum and, having suffered extensive bombing damage in World War II, was abolished in 1954.

William Cecil, Lord Burghley died on 4 August 1598 at the age of eighty-seven. “Long was his suffering” wrote John E. Neale, “yet still did he serve the Queen with his lively mind and his frail body to the end”. The Queen didn’t want to let her trusted friend go, neither from office nor from this world. She had once said to him that she did not wish to live longer than he did. On his death bed, she spooned him. Shortly before he died he wrote his son: “Serve your Queen and you serve God.”

The old man bequeathed money and jewellery with a total value of ₤14,000 along with the inventory of his castles and an income of ₤500 per annum from rent from his lands, to his two granddaughters Bridget and Susan de Vere. Elizabeth de Vere, Countess of Derby was provided for in a similar manner, when she got married in 1595. In this manner, the money that Edward de Vere lost to the crown came back to his family, though not to his own pocket. After his daughter had grown richer than he, Oxford made one last effort to persuade Queen Elizabeth to grant him the trade monopoly for tin. To this purpose, he sent a rather vehement letter to his brother in law, Robert Cecil in June 1599.

William and Robert Cecil

The chief justice, Sir John Popham and the courtier, Sir John Fortescue had informed him of the Queen’s wishes, that he acquire money for the mining of tin in Cornwall and Devonshire. Having found businessmen who were prepared to invest ₤10,000 per annum in the project, Oxford informed the chief justice accordingly. He received a somewhat delayed reply saying that Sir John Fortescue had an appointment to discuss the matter with the Queen on the following day. However, Sir John Fortescue didn’t feel well on the following day so he cancelled the appointment. To the best of Oxford’s knowledge at this point in time, the Queen had not been informed of the ₤10,000 that he had managed to acquire. On the contrary, the Lord Mayor even told the potential investors that the Queen was not prepared to invest in the mining project. Oxford then wrote that there was never any question of the Queen investing money, only of earning money. At an approximation, 500 tons of tin could be mined each year. The Queen could buy a ton of tin at ₤53 and sell at ₤84, thus earning an annual profit of more than ₤15,000. Why had he been instructed to find investors only to be made a fool of? Somewhat in anger, he writes the following letter to the Queen:

I dare not say how much your Majesty is abused but I find myself much grieved to be set on to compass this money and, having compassed it, to be turned out with such a mockery. I beseech your Majesty, in whose service I have faithfully employed myself, I will not entreat that you suffer it yourself thus to be abused but that you will not suffer me thus to be flouted, scorned & mocked.

The Earl didn’t understand that nobody’s honour was at stake here, it was merely a question of “who was going to give the middle men in the government the biggest bribe”. In this case, the mining investor Bevis Bulmer, successful in the silver and gold business since the fifteen seventies, was prepared to offer the necessary sweetener to the public servants.

Oxford writes to his brother in law, Robert Cecil, again in 1600. This time concerning a question about the governorship of the island of Jersey.

Although my bad success in former suits to her Majesty have given me cause to bury my hopes in the deep abyss and bottom of despair, rather than now to attempt, after so many trials made in vain & so many opportunities escaped, the effects of fair words or fruits of golden promises, yet for that I cannot believe but that there hath been always a true correspondency of word and intention in her Majesty, I do conjecture that, with a little help, that which of itself hath brought forth so fair blossoms will also yield fruit ... If she shall not deign me this in an opportunity of time so fitting, what time shall I attend (which is uncertain to all men) unless in the graves of men there were a time to receive benefits and good turns from princes? Well, I will not use more words, for they may rather argue mistrust than confidence. I will assure myself and not doubt of your good office, both in this but in any honourable friendship I shall have cause to use you. Hackney.

Your loving and assured friend and brother.

Edward Oxenford

Oxford’s hopes of worldly advancement were once again disappointed. The Queen considered her poet to be adequately provided for.

One of the most famous comedians of the day, Robert Armin, visited the Earl of Oxford at his residence in Hackney on Christmas 1599. Armin had just joined The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. He played the characters of “Touchstone” in As You Like It, “Autolycus” in Winter’s Tale, “Lavache” in All’s Well That Ends Well and “Thersites” in Troilus and Cressida.

Robert Armin on stage

In the foreword to his joke book Quips upon Questions (1600) he remarks that “on Tuesday” [25 December 1599] he would take his journey to Hackney “to wait on the right Honourable good Lord my Master whom I serve”. The purpose of the visit is obvious; the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were to play before the Queen on the following day. The comedian obviously wanted to get a couple of final pointers from the author before the performance. Had he wished to speak with the other Lord Chamberlain (George Carey 2nd Baron Hunsdon) then he would not have been going to Hackney where the Lord Great Chamberlain, Edward de Vere lived, but to Blackfriars.

England’s political climate again became turbulent during the last years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. Essex’ Irish campaign failed to achieve its aims; he paid little or no attention to the Queen’s orders, he had been soft with Tyrone, the rebellious Irish chieftain, he knighted his most loyal followers and then at the end of September 1599 he came back home on his own initiative and stormed in to the Queen’s chamber in a pair of dirty boots, thereby surprising her while she was half dressed. He got on his knees and begged forgiveness, the Queen showed regal decorum, although her hair was all over the place, and told him to go home. She waited a while until he felt lulled into false security then she had him arrested. Essex fell ill causing everybody to feel sorry for him, including the Queen.

Following the advice of her legal counsellor, Francis Bacon, the Queen didn’t put Essex on trial as this could have forced her into explaining her policies to the High Court. The philosopher argued that Essex’ political position was far too strong. In March 1600 he was allowed to live in his own house, under guard, in spite of ardent warnings from Sir Walter Raleigh. Essex was ordered before a special commission of the Privy Council in June where they demanded his subservience, though at the same time, offering him a chance to resume his duties in the service of the crown. The, once, arrogant man “quenched all the sparkles of pride that were in him” and at the end of August he was free to go where he wished in the realm, though not in the court of the Queen. As if he were parodying himself (or Henry Willobie) he began to write love letters to the Queen: “Haste paper to that happy presence whence only unhappy I am banished! Kiss that fair correcting hand which lays now plasters to my lighter hurts, but to my greatest wound applieth nothing.”

Essex’ declarations of love were false. Through mediators, he had secretly negotiated with the King of Scotland, plotting to set him on the throne of England. In the beginning of February 1601, Essex’ followers around the country received their secret code word, telling them to gather in London. The armed revolt against the crown was actually going to take place. Several ringleaders met on 3 February in the house of his friend Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, to organize the palace revolution. However the Privy Council got wind of the matter and their reaction was to issue a writ of summons to the Earl. Claiming to be ill, he refused to turn up. In an attempt to raise their spirits, Essex’ followers rented Burbage’s Globe and ordered a performance of Shakespeare’s King Richard II.

The theme of the play, as is common knowledge, is the removal of an incompetent King from power. Up to this point Essex’ plans had been clumsy and stupid, but to actually stage a propagandistic play signalling their plans were utterly inept.

The wildest plans were made that night to mobilize the City of London behind the rebellious Earl. On the morning of 8 February 1601, four representatives of the crown went to Essex’ House where they were threatened and taken hostage. Essex, accompanied by 200 of his followers rode forth and shouted into the crowd that his enemies had sold England to the Spaniards and were now trying to murder him. In the meantime Robert Cecil didn’t wait for the grass to grow under his feet: He sent a herald after the rebels who denounced Essex as a traitor. Hearing this statement from the official mouthpiece of the Queen had its desired effect. The would-be rebels realised the seriousness of the situation and distanced themselves from Essex. The rebel had to turn back. Finding the west gate to the city closed, Essex fought his way through to the Thames, tried to get back to his castle by boat, and was almost drowned. That was the end of a rebellion as ill-fated as ill-planned.

A week later the Earl of Essex and the Earl of Southampton were put on trial on the charge of treason. On the panel of judges, Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford.

A macabre situation: Shakespeare’s Adonis had now lowered himself to being the accomplice of a lying megalomaniac, or as Elizabeth called him: “a senseless ingrate”. The poet, who had immortalized him as the epitome of truth and beauty, now had to decide whether he should live or die.

On the morning of 25 February 1601, Essex made his way to the headsman’s block. In his last hour he was repentant and said that the state of England was right to spew him out.

The fate of Southampton is unique for this period in English history. Though sentenced to death, the Queen commuted his sentence to imprisonment in the Tower of London. (Two years later James I was only too pleased to restore his friend to freedom.)

William Shakespeare reacted to Essex’ treason and that of his friend Southampton by writing one of the last dramas of his life: Troilus and Cressida. This unusual play, so difficult to categorize with its sudden switches from bawdy comedy to tragic gloom is the story of treason and the collapse of moral integrity during times of war.

The siege of Troy provides the backcloth for this play: A horde of skulking desperate, crafty Greeks stand against the honour obsessed Trojans. In the end the Greek trickery is victorious over the fanatical Trojan code of honour.

The Earl of Essex is mirrored by the depraved Prince Achilles who exchanges letters with the Trojans. This Achilles, “the idol of idiot worshippers”, rests on the laurels of past glories. He is arrogant, lazy, insolent and bad tempered. Without consulting anybody, Achilles negotiates his own truce with the Trojans, and adopts the sneering young Patroclus as his favourite, perhaps his lover. When Hector kills Patroclus Achilles fights him, in single combat. Achilles is defeated, but later on, when Hector is unarmed, Achilles sets his Myrmidons on him. They kill him like a murderous swarm of ants.

In a portrait from 1603 we see Southampton’s

gaunt features and long hair.

He sits for the painter in his room with his cat.

The feline and the aristocratic model both observe the painter

with similar disdain.

Achilles’ friend, Patroclus, is a man devoid of character, a master of pretence, or as the cynical Thersites says, a male whore. “Ah, how the poor world is pest’red with such waterflies – diminutives of nature!” (V/I)

One could call the play a tragic satire, the sarcastic reaction to a set of values that are, at least, in the process of destruction, if not already completely destroyed. The bawdy moments aren’t funny; the tragic themes don’t come to any solutions. This anti-war drama ends with Achilles’ inglorious victory over Hector. Treachery is victorious; the fall of Troy is imminent.

Troilus and Cressida must have been written at some time between June 1601 and July 1602, because the play makes references to the “Poets’ War” that was fought out between Ben Jonson, John Marston and Thomas Dekker in 1601.

Ben Jonson

The ambitious dramatist, Ben Jonson (1572–1637) was very fond of making sarcastic mocking remarks about Shakespeare’s works. In his Poetaster (1601) he brings Captain Tucca, a crotchety version of Falstaff, to the stage. He parodies the welcome of the players in Hamlet and the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet. – Jonson had already poked fun at Shakespeare in 1599, in Every Man Out of his Humour, when he said of his own play: “That the argument of his comedy might have been of some other nature, as of a duke to be in love with a countess, and that countess to be in love with the duke’s son, and the son to love the lady’s waiting maid; some such cross wooing, with a clown to their servingman, better than to be thus near, and familiarly allied to the time.”

Shakespeare avenged himself for this impudence by saying of the oafish pseudo-hero, Ajax, representative for Jonson:

This man, lady, hath robb’d many beasts of their particular additions: he is as valiant as a lion, churlish as the bear, slow as the elephant – a man into whom nature hath so crowded humours that his valour is crush’d into folly, his folly sauced with discretion. There is no man hath a virtue that he hath not a glimpse of, nor any man an attaint but he carries some stain of it; he is melancholy without cause and merry against the hair; he hath the joints of every thing; but everything so out of joint that he is a gouty Briareus, many hands and no use, or purblind Argus, all eyes and no sight. (Troilus and Cressida, I/2)

This caustic passage was a slap in the face that Ben Jonson wouldn’t forget so soon. The clown William Kempe commented on the matter in the satire The Return from Parnassus (1602): “O that Ben Jonson is a pestilent fellow, he brought up [his] Horace giving the Poets a pill, but our fellow Shakespeare hath given him a purge that made him bewray his credit.” (See also p. 14)

While people were joking about the confusion caused by Shakespeare and Shaksper, the real life spear-shaker, the dramatist Edward de Vere resided in Hackney. He was ill that time. At his side, a woman who, according to contemporary documents, could be very un-pleasant when she so wished. (She accused his longstanding servant, Arthur Milles, of stealing and tried to get ₤60,000 compensation from him, whereby Arthur Milles claimed that he had to sell his own lands that brought in ₤200 per annum, so that he may stay in Oxford’s service.)

Even the Queen who once had enjoyed life to the full, felt “creeping time at her gate”. The seventeenth of November 1602 was the twenty fourth anniversary of her coronation and she was celebrated “with as great an applause of multitudes as if they had never seen her before”.

During the harsh winter of that year the seventy year old Queen moved her court from frosty Whitehall to somewhat warmer Richmond. To no avail.

During a theatrical performance in March 1603 she broke down. She allowed herself to be led to her room, but she refused to go to bed. She sat, or sometimes lay on a cushion on the floor often holding a finger to her lips, and wished neither food nor drink. When she had finally taken to her bed, the Privy Council assembled around her bed to discuss the future of the throne. With a nod of her head she recognized James VI, Margaret Tudor’s great grandson, as her successor. Whilst Bishop John Whitgift was reading from the bible she lost consciousness and on the morning of 24 March 1603, she died.

The Funeral of Queen Elizabeth, 28 April 1603

The proclamation, made by the Lord Mayor and the Privy Council, on 24 March 1603, declaring James VI to be the new King of England, was also signed by Oxford.

James, who had been raised as a protestant and humanist in Scotland, a diligent, ambitious, though easily influenceable and therefore not always a wise regent, had always been on the look out for potential allies in England. After the demise of Essex he secretly corresponded with the Secretary of State, Robert Cecil.

After the death of Elizabeth, the question of paramount interest at court was that of positioning oneself best, so as to be noticed when the new god came down from Edinburgh.

The Lord Great Chamberlain didn’t wish to be forgotten in the turmoil either. Who knows, perhaps the new monarch’s coronation would herald the resurrection of Oxford’s star. Be that as it may, on the day of King James’ arrival, Oxford greeted him in a fitting manner. On 25 April 1603 he writes Robert Cecil:

Sir Robert Cecil: I have always found myself beholding to you for many kindnesses and courtesies, wherefore I am bold at this present, which giveth occasion of many considerations, to desire you as my very good friend and kind brother-in-law to impart to me what course is devised by you of the Council & the rest of the Lords concerning our duties to the King’s Majesty, whether you do expect any messenger before his coming to let us understand his pleasure, or else his personal arrival to be presently or very shortly. And, if it be so, what order is resolved on amongst you, either for the attending or meeting of his Majesty for, by reason of mine infirmity, I cannot come among you so often as I wish, and by reason my house is not so near that at every occasion I can be present, as were fit...

The Earl leaves the letter on his own desk for two days until the day before Elizabeth’s official funeral. Shortly before sending it off, he writes the following, solemn appendage.

I cannot but find a great grief in myself to remember the mistress which we have lost, under whom both you and myself from our greenest years have been in a manner brought up and, although it hath pleased God after an earthly kingdom to take her up into a more permanent and heavenly state wherein I do not doubt but she is crowned with glory, and to give us a prince wise, learned and enriched with all virtues, yet the long time which we spent in her service we cannot look for so much left of our days as to bestow upon another, neither the long acquaintance and kind familiarities wherewith she did use us we are not ever to expect from another prince, as denied by the infirmity of age and common course of reason.

In this common shipwreck, mine is above all the rest who, least regarded though often comforted of all her followers, she hath left to try my fortune among the alterations of time and chance, either without sail whereby to take the advantage of any prosperous gale or with anchor to ride till the storm be overpast. There is nothing therefore left to my comfort but the excellent virtues and deep wisdom wherewith God hath endued our new master and sovereign Lord, who doth not come amongst us as a stranger but as a natural prince, succeeding by right of blood and inheritance, not as a conqueror but as the true shepherd of Christ’s flock to cherish and comfort them. Wherefore I most earnestly desire you of this favour, as I have written before, that I may be informed from you concerning these points and thus, recommending myself unto you, I take my leave.

Your assured friend and unfortunate brother-in-law,

E. Oxenford

A final tribute to the great woman to whom Oxford didn’t owe any material wealth, but much more: she had encouraged his genius. He was powered by her enthusiasm for the stage. She offered him the most cultivated venues in Europe. He rewarded her faith in him with his work.

After King James was settled in London Oxford petitioned him for the return of the lands that he regarded as his inheritance; Waltham Forest and Havering Park, an issue for which Oxford had fought since 1579. A miracle occurred; Waltham Forest and Havering Park were both returned. A week later, the official coronation ceremony of King James took place, he was handed the silver bowl and the silver jug for the ceremonial cleansing by the Lord Great Chamberlain Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford.

In the beginning of August James determined that the annual sum of ₤1,000 should be paid to the Earl for the rest of his life.

We can only guess at the events of the last year of Oxford’s life. All that we have to go by is a letter he wrote to the King on the subject of the return of his properties. The handwriting shows no signs of frailty. We don’t know which illness it was that caused Oxford’s paralysis. We don’t know anything about his state of mind towards the end, or of the last thing that he got angry about, his last joke, his last words.

On a summer’s day in 1604, one week before he died, he left all of his worldly goods to Francis Trentham, his wife’s brother and Radulph Snead, her uncle. He leased his property to the trustees his cousin Sir Francis Vere and his son-in-law Lord Norris of Rycote for a limited time and by so doing he safeguarded the said property from the jurisdiction of the crown. (The property changed from being “unmovable” to “movable” – one could call this strategy “legal alchemy”.) This stroke of genius saved his eleven year old son all the problems of being a ward of the crown that Edward de Vere had been subject to.

View of St Augustine’s Tower, c.1750

On 24 June 1604 Edward de Vere died within the encloses of “King’s Place”. According to the parish register, he was buried in the parish church of Hackney, two weeks later. From the church, only the steeple remains, not far from the railway lines were the trains rattle along.

BIBLIOGRAPHY to Anonymous SHAKE-SPEARE, The Man Behind

A. Frequently used Sources and Literature

Manuscripts

British Library, MS. Harleian 7392 (2), Coningsbye [Humphrey Coningsby]

Bodleian Library, MS. Rawlinson Poet. 85 [John Finet]

Folger Library, MS. V.a.89, Anne Cornwallis Her Booke

Basic Literature

Bloom, Harold: Shakespeare – The Invention of the Human. New York 1998

Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series of the Reigns of Edward VI, Mary, Elizabeth, Preserved in the State Paper Department of Her Majesty’s Public Record Office (5 vols), ed. by Robert Lemon and Mary Anne Everett Green. London 1856–1872 [net: www.british-history.ac.uk]

Chambers, Edmund K.: William Shakespeare – A Study of Facts and Problems (2 vols). Oxford 1930

Greenblatt, Stephen: Will in the World. How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. New York 2004

Lewis, C.S.: English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, Oxford 1954

May, Steven W.: The Poems of Edward DeVere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, and of Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex, Studies in Philology, 1980

May, Steven W.: The Elizabethan Courtier Poets, The Poems and their Contexts. Columbia, 1991

Michell, John: Who wrote Shakespeare? London 1999

Muir, Kenneth: The Sources of Shakespeare’s Plays, London 1977

Neale, John E.: Queen Elizabeth. London 1934

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (60 vols), Oxford 2004

Read, Conyers: Lord Burghley and Queen Elizabeth. London 1960

Shakespeare, William: The Arden Shakespeare, Complete Works. Ed. by Richard Proudfoot, Ann Thompson, David Scott Kastan. London 2003

Wright, Thomas (ed.): Queen Elizabeth and her times – original letters [Burghley, Leicester, Walsingham, Smith, Hatton] (2 vols). London 1838

Oxfordian Literature

Looney, J. Thomas: Shakespeare Identified in Edward de Vere, The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. New York 1920 [1948]

Ward, B[ernard] M.: The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford 1550–1604. From Contemporary Documents, London 1928

Holland, H[ubert] H[enry]: Shakespeare, Oxford and Elizabethan times. London 1933

Barrell, Charles Wisner: The Writings of Charles Wisner Barrell, 1940–1948. In: The Shakespeare Fellowship News-Letter (American) and The Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly (American) [net: Shakespeare Authorship Sourcebook]

Ogburn, Charlton [jun.]: The Mysterious William Shakespeare. The Myth and the Reality. 2nd Edition. Virginia 1992

Sobran, Joseph: Alias Shakespeare. Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time. New York 1997

Stritmatter, Roger: The Marginalia of Edward de Vere’s Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence. Northampton 2001

Malim, Richard (ed.): Great Oxford. Essays on the Life and Work of Edward de Vere, 17 th Earl of Oxford, 1550 – 1604. Tunbridge Wells 2004

Anderson, Mark: Shakespeare by Another Name. New York 2005

Kreiler, Kurt (ed.): Fortunatus im Unglück. Die Aventiuren des Master F. I. Von Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. [The Adventures of Master F. I.] Frankfurt/Main 2006

Farina, William: De Vere as Shakespeare: An Oxfordian Reading of the Canon. Jefferson 2006

Detobel, Robert: Detobel’s Collected Essays, 2009. [net: www.elizabethanauthors.org]

Kreiler, Kurt: Der Mann, der Shakespeare erfand. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Franfurt/Main 2009

Detobel, Robert: Shakespeare. The concealed poet. Amsterdam 2010 [net: Shake-speare-today]

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010 [net: e-book, HarperCollins]

Kevin Gilvary (ed.): Dating Shakespeare’s Plays: A Critical Review of the Evidence. Tunbridge Wells 2010

B. Literary References in the Order of their Appearance in the Presentation

The Collapse of the Monument

Lewis, B. Roland (ed.): The Shakespeare Documents, Facsimiles, Transliterations, Translations & Commentary (2 vols). London, 1940

William Shakespeare: The Life Records, vol. 263 in Gale’s Dictionary of Literary Biography. Ed. by Catherine Loomis. 2002

Twain, Mark: Is Shakespeare dead? New York and London 1909

Bryson, Bill: Shakespeare. The World as Stage. London 2007

Foakes, Reginald A. (ed.): Henslowes Diary. Cambridge 2000

Gurr, Andrew: The Shakespeare Company, 1594 – 1642. Cambridge 2004

Detobel, Robert: Detobel’s Collected Essays, 2009

Bednarz, James: Shakespeare & the Poets’ War. New York 2001

Invited to write, he was in pain

Green, Martin: Wriothesley’s Roses in Shakespeare’s Sonnets, Poems and Plays. Baltimore 1993

Martindale, Charles / Burrow, Colin: Clapham’s Narcissus, A Pre-Text for Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis? In: English Literary Renaissance 22 (1992), p.147–76

The Author of the Plays

Titus Andronicus

Chambers, E. K.: The First Illustration to ‘Shakespeare’. In: The Library, V (1925), pp. 326–30

Adams, Joseph Quincy: Introduction to Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus: The First Quarto, 1594, Reproduced in Facsimile. New York 1936

Wilson, John Dover: Titus Andronicus’ on the Stage in 1595. In: Shakespeare Survey 1 (1948): 17–22, esp. 19

Eugene M. Waith ( ed.): Titus Andronicus. Oxford, 1984

Parrott, Thomas M.: Further Observations on Titus Andronicus , Shakespeare Quarterly, 1950

Young, Alan R.: Henry Peacham’s manuscript emblem books, 1998

Roper, David: Henry Peacham’s Chronogram: the Dating of Shhakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, in: Great Oxford, Essays on the Life and Work of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Tunbridge Wells 2004

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010

Sullivan, Edward: Shakespeare and Italy. In: The Nineteenth Cantury and After, Jan./Febr. 1918

Grillo, Ernesto: Shakespeare and Italy. Glasgow 1949 (New York 1973)

Praz, Mario: The Flaming Heart: Essays on Crashaw, Machiavelli, and Other Studies in the Relations between Italian and English Literature from Chaucer to T. S. Eliot. New York 1958

Schott, Franciscus: Itinerarii Italiae rerumque Romanarum Libri tres, Antwerpen 1600

Romeo and Juliet

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010

The Merchant of Venice

Elze, Theodor: Venezianische Skizzen zu Shakespeare. München 1899

Jeffery, Violet M.: Shakespeare’s Venice. In: The Modern Language Review, 1932

Pighius, Stephan Vinandus: Hercules Prodicius seu principis iuventutis vita et peregrinatio. Antwerpen 1587

Montaigne, Michel de: Journal du voyage de Michel de Montaigne en Italie par la Suisse & l’Allemagne en 1580 & 1581. Paris 1774

Schott, Franciscus: Itinerarii Italiae rerumque Romanarum Libri tres, Antwerpen 1600

Hentzner, Paulus: Itinerarium Germaniae, Galliae, Angliae, Italiae, Nuremberg 1612

Vincenzo Coronelli: La Brenta quasi borgo della citta di Venezia luogo di delizie del Veneti patrici, Venezia 1711

Kreiler, Kurt: Der Mann, der Shakespeare erfand. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Franfurt/M. 2009

Gosson, Stephen: The Schoole of Abuse. London 1579

Harvey, Gabriel: Letter-Book, A.D. 1573–1580. Ed. by Edward J. L. Scott, 1884

The Taming of the Shrew

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010

Measure for Measure

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010

All’s Well That Ends Well

Grillo, Ernesto: Shakespeare and Italy. Glasgow 1949 (New York 1973)

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010

Much Ado about Nothing

Roe, Richard Paul: The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, Then and Now. Pasadena 2010

Beeching, Jack: The Galleys at Lepanto. New York 1982

Love’s Labour’s Lost

Kreiler, Kurt: Der Mann, der Shakespeare erfand. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Franfurt/Main 2009

Phelps, John: The source of Love’s Labour’s Lost, in: The Shakespeare Association Bulletin, vol. 17, no. 2, April, 1942

Harbage, Alfred: Love’s Labor’s Lost and the Early Shakespeare, in: Philological Quarterly 61, No.1, Jan. 1962

Yates, Frances A.: A Study of Love’s Labour’s Lost. Cambridge 1936

Hamlet

Wilson, J. Dover: The Puritan Attack upon the Stage, in: The Cambridge History of English Literature, Ed. A. W. Ward and A. R. Waller, Vol. VI, The Drama to 1642, Part Two. Cambridge 1910

Gager, William: Dido tragoedia. Herausgegeben, übersetzt, eingeleitet und kommentiert von Uwe Baumann und Michael Wissemann. Frankfurt/M. 1985

Kreiler, Kurt: Der Mann, der Shakespeare erfand. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Franfurt/M. 2009

Bullough, G[eoffrey]: The Murder of Gonzago. In: The Modern Language Review Vol. 30, No. 4, Oct., 1935

Viani, E[lisa]: L’avvelenamento [poisoning] di Francesco Maria I Della Rovere Duca d’Urbino. Mantova 1902

The Discovery of the Key

Thomas Edwards (1593)

Barrell, Charles Wisner: Rarest contemporary Descriptions of “Shakespeare”, 1948. In: The Writings of Charles Wisner Barrell, 1944–1948, The Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly (American) [net: Shakespeare Authorship Sourcebook]

Henry Willobie (1594)

Luna, B[arbara] N[ielsen] de: The Queen Declined. An Interpretation of Willobie his Avisa. With the Text of the Original Edition. Oxford 1970

Henry Chettle (1603)

Robert Detobel: Neue Spuren zu Shakespeare. In: Neues Shake-speare Journal 3. 1999, pp. 98–150

John Davies of Hereford (1611/1616)

May, Steven W.: The Authorship of ‘My Mind to me a Kingdom is’, in: The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 26, Nov. 1975

Davies of Hereford, John: The Complete Works of John Davies of Hereford, ed. by Alexander B. Grosart (2 vols). Edinburgh 1878 (Reprint Hildesheim 1968)

Detobel, Robert: Detobel’s Collected Essays, 2009. [net: www.elizabethanauthors.org]

The Harvey-Nashe Quarrel

Strange Newes

Nicholl, Charles: A Cup of News. The Life of Thomas Nashe. Routledge 1984

Barrell, Charles Wisner: Gentle Master William. In: The Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly, V.4, Oct. 1944

Detobel, Robert: Eine Widmung. In: Neues Shake-speare Journal 4, 1999, S. 72–116

Or a New Praise of the Old Ass

Kreiler, Kurt: Der Mann, der Shakespeare erfand. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Franfurt/M. 2009

The said unmatchable great A.

Detobel, Robert: Neue Spuren zu Shakespeare, in : Neues Shake-speare Journal 3, 1999, S. 98–150

Kreiler, Kurt: Der Mann, der Shakespeare erfand. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Franfurt/Main 2009

Harvey, Gabriel: Gabrielis Harueij Gratulationum Valdinensium libri quatuor ... Londini : Ex officina typographica Henrici Binnemani, Anno. M.D.LXXVIII [1578] Mense Septembri. (See 3.1.1 Harvey, Gratulationes.)

Harvey, Gabriel: The Gratulationes Valdinenses, ed. by Thomas Hugh Jameson. Yale University 1938 [net: www.oxford-shakespeare.com]

The Biography I (1550–1583)

Ward, B[ernard] M.: The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford 1550–1604. From Contemporary Documents, London 1928

Nelson, Alan H.: Monstrous Adversary. The Life of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Liverpool 2003 [see: Peter R. Moore: Demonography 101. In: Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, Shakespeare Oxford Society. Washington, Dec. 2004]

Dewar, Mary: Sir Thomas Smith, A Tudor Intellectual in Office. London 1964

Alford, Stephen: Burghley. William Cecil at the Court of Elisabeth I New Haven and London 2008

Golding, Louis Thorn: An Elizabethan puritan. [Arthur Golding] New York 1937

Boas, Frederick S.: University Drama in the Tudor Age. New York 1971

Bradner, Leicester: The Life and Poems of Richard Edwards. New Haven, London, Oxford 1927

Prouty, Charles Tyler: George Gascoigne. Elizabethan Courtier, Soldier and Poet. New York 1942

Douce, Francis: Illustrations of Shakspeare and of Ancient Manners. London 1807

Hunter, Joseph: New Illustrations of Shakespeare of the Life, Studies, and Writings of Shakespeare. London 1845

Campbell, Lily B.: Shakespeare’s Tragic Heroes. Cambridge 1930

Craig, Hardin: Hamlet’s Book, in: Huntington Library Bulletin 6, 1934, pp. 17–37

Kemp, Thomas (ed.): The Black Book of Warwick. Warwick 1898 (B. M. Ward, The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, pp. 69–71; A. H. Nelson: Monstrous Adversary, pp. 84–86)