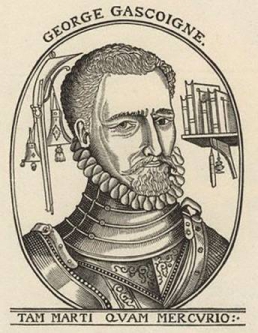

7.2.2. George Gascoigne, The Fruites of War

The soldier poet George Gascoigne (c. 1535-1577) set out from England to

Holland in April 1572, came back to England in November 1572, and returned to

Holland on 19 March 1573 along with Captain Thomas

Morgan’s first military detatchment. In 1573 Gascoigne, together with his friends Rowland York (a mutual friend

of the Earl of Oxford) and William Herle[1] had a narrow escape

when the Dutch pilot got drunk and ran their boat aground on the

coast: twenty men were drowned. Gascoigne finished his poem

Voyage to Holland before the end of March, and sent it to

England so that it could appear in the anthology A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres,

which was already in print. In England, the calendar year 1572 was over

on 24th March 1573. In spite of the fact that the Flowres

did not appear until April 1573, the title page with the date 1572 was not

changed. This means that "Meritum petere grave", the co-author of

A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, who was supervising the printing,

had opportunity to include Gascoigne's Voyage to Holland

at the very last moment.

As was demonstrated in 5.0 Introduction the person behind the

posy "Meritum petere grave" was none other than the poet Edward de Vere,

Earl of Oxford, who was very adept in hiding his contributions to

A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres. Consequently, we can assume a

certain closeness, perhaps even friendship existed between the two

men up to that point.

Gascoigne belonged to Morgan's regiment in 1573 and changed to Edward

Chester's regiment in 1574, having probably quarrelled with Morgan.

After the disastrous defeat of Chester's regiment near Leiden in 1574 he

was taken prisoner by the Spanish who released him on payment of his ransom.

"The poem The Fruites of War," says Henry Morley, "is of some length and of higher aim. It is one of the best of Gascoigne's poems, and includes incidentally a sketch of his adventures in the Netherlands. Written in the midst of an inevitable war for independence, it sets forth the truth that war is evil in itself, and always bom of evil. It is a poet's moralising on a saying found by Gascoigne in the Adages of Erasmus, and of which Erasmus also had enforced the truth: Dulce Bellum Inexpertis. Gascoigne's incidental record of his own experience deals mainly with service in and near the Isle of Walcheren. He was one of a little force that for seven days protected the small unwalled town of Aardenburg, four miles from Sluys, and saved it from attack. He was, like Churchyard, in the trenches before Ter-Goes, or Goes, a fortified town on the island of South Beveland, held by Spaniards.“ (Henry Morley, English Writers, From Surrey to Spenser. London 1892).

We may assume that Oxford hurried to his friend's side with the

necessary ransom money after his capture in May 1574. Only when regarded in this

context does Oxford's trip to Flanders, in July 1574, make any sense.

(See 7.2.3 Oxford in Flanders.)

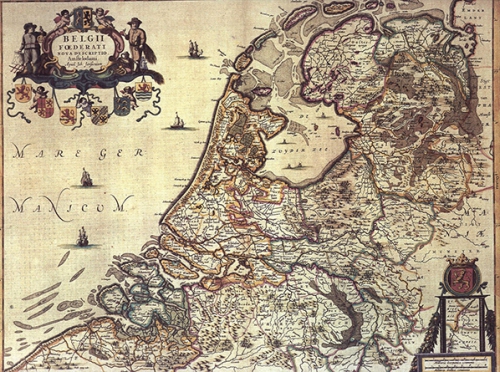

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jansoni.jpg

1. George Gascoigne, The Fruits of War,

written upon this theme,

Dulce Bellum inexpertis.[2]

95 For I have seen full many a Flushing fray [attack, fight],

And fleeced [combed] in Flanders eke among the rest,

The brag of Bruges [3], where was I that day?

Before the walls good sir as brave as best,

And though I marched all armed withouten rest,

From Aerdenburgh [Aardenburg] and back again that night,

Yet mad were he that would have made me knight.

96 So was I one forsooth that kept the town,

Of Aerdenburgh [4] (withouten any walls)

From all the force that could be dressed down,

By Alba Duke for all his cries and calls,

A high exploit. We held the Flemings thralls,

Seven days and more without or brags or blows,

For all that while we never heard of foes.

97 I was again in trench before Tergoes [Goes], [5]

(I dare not say in siege for both mine ears)

For look as oft as ever Hell brake lose,

I mean as often as the Spanish peers,

Made sally forth (I speak this to my feres)

It was no more but which Cock for a groat,

Such troops we were to keep them up in coat.

98 Yet surely this withouten brag or boast,

Our English bloods did there full many a deed,

Which may be Chronicled in every coast,

For bold attempts, and well it was agreed,

That had their heads been ruled by wary heed,

Some other feat had been attempted then,

To show their force like worthy English men.

99 Since that siege raised I roamed have about,

In Zeeland, Holland, Waterland, and all,

By sea, by land, by air, and all throughout,

As leaping lots, and chance did seem to call,

Now here, now there, as fortune trilled the ball,

Where good Guillam of Nassau [6] bad me be,

There needed I none other guide but he.

100 Percase [perchance] sometimes S. Gyptian's pilgrimage[7]

Did carry me a month (yea sometimes more)

To brake the Bowers[8], and rack them in a rage,

Because they had no better cheer in store,

Beef, Mutton, Capon, Plover, Pigeons, Boar,

All this was naught, and for no Soldier's tooth,

Were these no jars? (speak now Sir) yes forsooth.

101 And by my troth to speak even as it is,

Such pranks were played by Soldiers daily there,

And though myself did not therein amiss,

(As God he knows and men can witness bear,)

Yet since I had a charge, I am not clear,

For seldom climbs that Captain to renown,

Whose Soldiers' faults so pluck his honour down.

102 Well let that pass. I was in rolling trench,

At Ramykins [Rammekens],[9] where little shot was spent,

For gold and groats their matches still did quench,

Which kept the Fort, and forth at last they went,

So pained for hunger (almost ten days pent)

That men could see no wrinkles in their faces,

Their powder packed in caves and privy places.

103 Next that I served by night and eke by day,

By Sea, by land, at every time and tide,

Against Mountdragon [10] whiles he did assay,

To land his men along the salt sea side,

For well he wist that Ramykins [Rammekens] went wide,

And therefore sought with victual to supply,

Poor Middleburgh[11] which then in suds did lie.

104 And there I saw full many a bold attempt,

By seely souls best executed aye,

And bravest brags (the foemen's force to tempt)

Accomplished but coldly many a day,

The Soldier charge, the leader lope away,

The willing drum a lusty march to sound,

Whiles rank retirers gave their enemies ground.

105 Again at Sea the Soldier forward still,

When Mariners had little lust to fight,

And whiles we stay twixt faint and forward will,

Our enemies prepare themselves to flight.

They hoist up sail (o weary word to write)

They hoist up sail that lack both stream and winds,

And we stand still, so forced by froward minds.

106 O victory: (whom Haughty hearts do hunt)

O spoil and pray (which greedy minds desire)

O golden heaps (for whom these Misers wont

To follow Hope which sets all hearts on fire)

O gain, O gold, who list to you aspire,

And glory eke, by bold attempts to win,

There was a day to take your prisoners in.

107 The ships retire with riches full yfraught,

The Soldiers march (meanwhile) into the town,

The tide scarce good, the wind stark staring naught,

The haste so hot that (ere they sink the sound [12])

They came on ground, and strike all sails adown:

While we (ay me) by backward sailors led,

Take up the worst when all the best are fled.

108 Such triumphs chance where such Lieutenants rule,

Where will commands when skill is out of town,

Where boldest bloods are forced to recoil

By Sim the boatswain when he list to frown,

Where Captains crouch, and fishers wear the Crown.

Such haps which happen in such hapless wars,

Make me to term them broils and beastly jars.

109 And in these broils (a beastly broil to write,)

My Colonel and I fell at debate,[13]

So that I left both charge and office quite,

A Captain's charge and eke a Marshal's state,

Whereby I proved (perhaps though all to late)

How soon they fall which lean to rotten bows,

Such faith find they, that trust to some men's vows.

110 My heart was high, I could not seem to serve,

In regiment where no good rules remain,

Where officers and such as well deserve,

Shall be abused by every page and swain

Where discipline shall be but deemed vain,

Where blocks are strid [stridden] by stumblers at a straw,

And where self-will must stand for martial law.

111 These things (with moe) I could not seem to bear,

And thereupon I cracked my staff in two,

Yet staid I still though out of pay I were,

And learn to live as private Soldiers do,

I lived yet, by God and lacked too:

Till at the last when Beauvoir [14] fled amain [vehemently],

Our camp removed to strain [pass] the land van Strain [Strijen].

112 When Beauvoir fled, Mountdragon came to town,[15]

And like a Soldier Middleburgh he kept,

But courage now was coldly come adown,

On either side: and quietly they slept,

So that myself from Zeeland lightly leapt,

With full intent to taste our English ale,

Yet first I meant to tell the Prince my tale.

113 For though the wars waxed cold in every place,

And small experience was there to be seen,

Yet thought I not to part in such disgrace,

Although I longed much to see our Queen:

For he that once a hired man hath been,

Must take his Master's leave before he go,

Unless he mean to make his friend his foe.

114 Then went I straight to Delf [Delft], a pleasant town,

Unto that Prince, whose passing virtues shine,

And unto him I came on knees adown,

Beseeching that his excellence in fine

Would grant me leave to see this country mine:

Not that I weary was in wars to serve,

Nor that I lacked what so I did deserve.

115 But for I found some conteck [discord] and debate,

In regiment where I was wont to rule,

And for I found the stay of their estate,

Was forced now in towns for to recoil,

I craved leave no longer but till Yule [Christmas],

And promised then to come again Sans fail [without doubt],

To spend my blood where it might him avail.

116 The noble Prince gave grant to my request,

And made me passport signed with his seal,

But when I was with bags and baggage prest,

The Prince began to ring another peal,

And sent for me, (desiring for my weal)

That I would stay a day or two, to see,

What was the cause he sent again for me.

117 My Colonel was now come to the Court [16],

With whom the Prince had many things to beat,

And for he hoped, in good and godly sort,

Tween him and me to work a friendly feat,

He like a gracious Prince his brains did beat,

To set accord between us if he might,

Such pains he took to bring the wrong to right.

118 O noble Prince, there are too few like thee,

If Virtue wake, she watcheth in thy will,

If Justice live, then surely thou art he,

If Grace do grow, it groweth with thee still,

O worthy Prince would God I had the skill

To write thy worth that men thereby might see,

How much they err that speak amiss of thee.

119 The simple Sots do count thee simple too,

Whose like for wit our age hath seldom bred,

The railing rogues mistrust thou darest not do,

As Hector did for whom the Grecians fled,

Although thou yet wert never seen to dread,

The slanderous tongues do say thou drinkst to much,

When God he knows thy custom is not such.

120 But why do I in worthless verse devise,

To write his praise that doth excel so far?

He heard our griefs himself in gracious wise,

And mildly meant to join our angry jar,

He meant to make that we began to mar:

But wicked wrath had some so far enraged,

As by no means their malice could be swayed.

121 In this mean while the Spaniards came so near

That Delf was girt with siege on every side [17],

And though men might take shipping everywhere,

And so be gone at any time or tide,

Yet truth to tell (I speak it for no pride)

I could not leave that Prince in such distress,

Which cared for me and yet the cause much less.

122 But see mishap how craftily it creeps,

Whiles fawning fortune flareth full in face,

My heavy heart within my belly weeps,

To reckon here a drop of dark disgrace,

Which fell upon my pleasant plight apace,

And brought a pack of doubts and dumps to pass,

Whiles I with Prince in love and favour was.

123 A worthy dame whose praise my pen shall write

(My sword shall eke her honour still defend)

A loving letter to me did indite

And from the Camp the same to me did send,

I mean from Camp where foes their force did bend:

She sent a brief unto me by her maid,

Which at the gates of Delf was stoutly stayed.

124 This letter tane [taken], I was mistrusted much,

And thought a man that were not for to trust,

The Burghers straight began to bear me grudge,

And cast a snare to make my neck be trust,

For when they had this letter well discussed:

They sent it me by her that brought it so,

To try if I would keep it close or no.

125 I red the lines, and knowing whence they came,

My harmless heart began to pant apace,

Well to be plain, I thought that never Dame

Should make me deal in any doubtful case,

Or do the thing might make me hide my face:

So that unto the Prince I went forthwith,

And showed to him of all this pack the pith.

126 The thing God knows was of no great import,

Some friendly lines the virtuous Lady wrote

To me her friend: and for my safe passport

The Campo-master Valdez [18] his hand was got,

And seal therewith, that I might safely trot

Unto the Hague [Den Haag] a stately pleasant place,

Whereas remained this worthy woman's grace.

127 And here I set in open verse to show,

The whole effect wherefore this work was wrought,

She had of mine (whereof few folks did know)

A counterfeit, a thing to me dear bought,

Which thing to have I many time had sought

And when she knew how much I did esteem it

She vowed that none but I should thence redeem it.

128 Lo here the cause of all this secret sleight,

I swear by Jove that nothing else was meant,

The noble Prince (who saw that no deceit

Was practised) gave trust to mine intent:

And leave to write from whence the same was sent,

But still the Bowgers [butchers] (Burghers should I say)

Increased their doubles [ruse] and watched me day by day.

129 At every port it was (forsooth) belast [forbidden],

That I (die groene Hopman [19]) might not go out,

But when their foes came skirmishing full fast,

Then with the rest the Green knight for them fought,

Then might he go without mistrust or doubt:

O drunken plumps, I plain without cause why,

For all cards told there was no fool but I.

130 I was the fool to fight in your defence,

Which know no friend, nor yet your selves full well,

Yet thus you see how pay proclaimed for pence,

Pulls needy souls instead of heaven to hell,

And makes men hope to bear away the bell.

Whereas they hang in ropes that never rot,

Yet war seems sweet to such as know it not.

131 Well thus I dwelt in Delf a winter's tide,

In Delf (I say) without one penny pay:

My men and I did cold and hunger bide,

To show our truth, and yet was never day,

Wherein the Spaniard came to make us play,

But that the Green knight was amongst the rest,

Like John Grey's bird that ventured with the best[20].

132 At last the Prince to Zeeland came himself

To hunger Middleburgh [Middelburg], or make it yield,

And I that never yet was set on shelf,

When any sailed, or wind, or waves could wield,

Went after him to show myself in field.

The self same man which erst I vowed to be,

A trusty man to such a Prince as he.

133 The force of Flanders, Brabant, Guelders, Frize [Frisia],

Henault, Artois, Liegeland, and Luxembourg,

Were all ybent, to bring in new supplies

To Middleburgh: and little all enough,

For why the Gueux would neither bend nor bow.

But one of force must break and come to nought,

All Walkers [Walcheren] theirs, or Flushing dearly bought.

134 There once again I served upon seas,

And for to tell the cause and how it fell,

It did one day the Prince (my chieftain) please,

To ask me thus: Gascoigne (quoth he) you dwell

Amongst us still: and thereby seemeth well,

That to our side you bear a faithful heart,

For else long since we should have seen you start.

135 But are (said he) your Soldiers by your side?

O Prince (quoth I) full many days be past,

Since that my charge did with my Coronel glide.

Yet bide I here, and mean to be with last:

And for full proof that this is not a blast

Of glorious talk: I crave some fisher boat

To show my force among this furious float.

136 The Prince 'gan like my faith and forward will,

Equipped a Hoy [21] and set her under sail,

Wherein I served according to my skill,

My mind was such, my cunning could not quail,

Withouten brag of those that did assail

The foemen's fleet which came in good array,

I put myself in foremost rank alway.

137 Three days we fought, as long as water served,

And came to anchor neighbour like yfere [together],

The Prince himself to see who best deserved,

Stood every day attending on the peer,

And might behold what bark went foremost there:

Ill heart had he that would not stoutly fight,

When as his Prince is present still in sight.

138 At last our foes had tidings over land,

That near to Bergh [Bergen-op-Zoom] their fellows went to wrack,

On Scheld they met by Rymerswaell [22] a band

Of Edellbloets [lusty gallants], who put their force aback,

Lewes de Boyzott [23] did put them there to sack,

And lost an eye, because he would resemble

Dan Julian [24], whom (there) he made to tremble.

139 When this was known Sancho de Avila [25],

Who had the charge of those that fought with us,

Went up the Hond [West Scheldt] and took the ready way,

To Anwerp town: leaving in danger thus,

Poor Middleburgh which now waxed dolorous

To see all hope of succour shrink away,

Whiles they lacked bread and had done many a day.

140 And when Mondrágon might no more endure[26],

He came to talk and rendered all at last,

With whom I was within the City sure,

Before he went, and on his promise past,

Such trust I had to think his faith was fast:

I dined, and supped, and lay within the town,

A day before he was from thence ybown [about to go].

141 Thus Middleburgh, Armew [Arnemuiden], and all the rest,

Of Walkers Ile [Walcheren] became the Prince's pray,

Who gave to me because I was so prest

At such a pinch, and on a dismal day,

Three hundred guilders good above my pay.

And bad me bide till his ability

Might better guerdon my fidelity.

142 I will not lie, these Guilders pleased me well,

And much the more because they came uncraved,

Though not unneeded as my fortune fell,

But yet thereby my credit still was saved,

My scores were paid, and with the best I braved,

Till (lo) at last an English new relief

Came over seas, and Chester [27] was their chief.

143 Of these the Prince persuaded me to take

A band in charge with Colonel's consent,

At whose requests I there did undertake,

To make mine ensign once again full bent,

And sooth to say, it was my full intent,

To loose the saddle or the horse to win,

Such hapless hope the Prince had brought me in.

144 Soldiers behold and Captains mark it well,

How hope is harbinger of all mishap,

Some hope in honour for to bear the bell,

Some hope for gain and venture many a clap,

Some hope for trust and light in treason's lap.

Hope leads the way our lodging to prepare,

Where high mishap (oft) keeps an Inn of care.

145 I hoped to show such force against our foes,

That those of Delf might see how true I was,

I hoped indeed for to be one of those

Whom fame should follow, where my feet should pass,

I hoped for gains and found great loss alas:

I hoped to win a worthy Soldier's name,

And lite [rely] on luck which brought me still to blame.

146 In Valkenburgh (a fort but new begone)

With others moe I was ordained to be,

And far before the work were half way done,

Our foes set forth our sorry seat to see,

They came in time, but cursed time for me,

They came before the curtain raised were,

One only foot above the trenches there.[28]

147 What should we do, four ensigns lately prest,

Five hundred men were all the bulk we bare,

Our enemies three thousand at the least,

And so much more they might always prepare:

But that most was, the truth for to declare,

We had no store of powder, nor of pence,

Nor meat to eat, nor mean to make defence.

148 Here some may say that we were much to blame,

Which would presume in such a place to bide,

And not foresee (how ever went the game)

Of meat and shot our soldiers to provide:

Who so do say have reason on their side,

Yet proves it still (though ours may be the blot)

That war seems sweet to such as know it not.

149 For had our fort been fully fortified,

Two thousand men had been but few enough

To man it once, and had the truth been tried,

We could not see by any reason how

The Prince could send us any succour now,

Which was constrained in towns himself to shield,

And had no power to show his force in field.

150 Herewith we had nor powder packs in store,

Nor flesh, nor fish, in powdering tubs yput,

Nor meal, nor malt, nor mean (what would you more?)

To get such gear if once we should be shut.

And God he knows, the English Soldier's gut,

Must have his fill of victuals once a day,

Or else he will but homely earn his pay.

151 To scuse ourselves, and Colonel withal,

We did foretell the Prince of all these needs,

Who promised always to be our wall,

And bad us trust as truly as our creeds,

That all good words should be performed with deeds,

And that before our foes could come so near,

He would both send us men and merry cheer.

152 Yea Robin Hood, our foes came down apace,

And first they charged another Fort likewise,

Alphen [29] I mean, which was a stronger place,

And yet to weak to keep in warlike wise:

Five other bands of English Fanteries [footmen],

Were therein set for to defend the same,

And them they charged for to begin the game.

153 This Fort from ours was distant ten good miles,

I mean such miles as English measure makes,

Between us both stood Leiden town there whiles [30]

Which every day with fair words undertakes

To feed us fat and cram us up with cakes:

It made us hope it would supply our need,

For we (to it) two Bulwarks were indeed.

154 But when it came unto the very pinch

Leiden farewell, we might for Leiden sterve [starve],

I like him well that promiseth an inch,

And pays an ell, but what may he deserve

That flatters much and can no faith observe?

An old said saw, that fair words make fools fain,

Which proverb true we proved to our pain.

155 A conference among ourselves we called,

Of Officers and Captains all yfere,

For truth (to tell) the Soldiers were appalled,

And when we asks, now mates what merry cheer?

Their answer was: it is no biding here.

So that perforce we must from thence be gone,

Unless we meant to keep the place alone.

156 Herewith we thought that if in time we went,

Before all straights were stopped and taken up,

We might (perhaps) our enemies prevent,

And teach them eke to taste of sorrows cup:

At Maeslandsluys [Maassluis] we hoped for to sup[31],

A place whereas we might good service do

To keep them out which took it after too.

157 Whiles thus we talk, a messenger behold,

From Alphen came, and told us heavy news.

Captains (quoth he) hereof you may be bold,

Not one poor soul of all your fellows' crews,

Can 'scape alive, they have no choice to choose:

They sent me thus to bid you shift in time,

Else look (like them) to stick in Spanish lime.

158 This tale once told, none other speech prevailed,

But pack and trudge [go away], all leisure was too long.

To 'mend the mart, our watch (which never failed)

Descried our foes which marched all along,

And towards us began in haste to throng,

So that before our last could pass the port,

The foremost foes were now within the Fort.

159 I promised once and did perform it too,

To bide therein as long as any would,

What booted [of what avail was] that? or what could Captains do,

When common sort would tarry for no gold?

To speak a troth, the good did what they could,

To keep the bad in ranks and good array,

But labour lost to hold that will away.

160 It needless were to tell what deeds were done,

Nor who did best, nor who did worst that day,

Nor who made head, nor who began to run,

Nor in retreat what chief was last alway,

But Soldier like we held our enemies' play:

And every Captain strave [strove] to do his best,

To stay his own and so to stay the rest.

161 In this retire three English miles we trod,

With face to foes and shot as thick as hail,

Of whose choice men full fifty souls and odd,

We rayed on ground, this is withouten fail,

Yet of our own, we lost but three by tale:

Our foes themselves confess they bought full dear,

The hot pursuit which they attempted there.

162 Thus came we late at last to Leiden walls,

Too late, too soon, and so may we well say,

For notwithstanding all our cries and calls,

They shut their gates and turned their ears away:

In fine they did forsake us every way,

And bad us shift to save ourselves apace,

For unto them were fond to trust for grace.

163 They neither gave us meat to feed upon,

Nor drink, nor powder, pickaxe, tool nor spade,

So might we starve, like miser's woe begone,

And fend our foes, with blows of English blade,

For shot was shrunk, and shift could none be made:

Yea more than this, we stood in open field,

Without defence from shot ourselves to shield.

164 This thus well weighed, the weary night was past,

And day 'gan peep, we heard the Spanish drums,

Which stroke a march about us round to cast,

And forth withal their Ensigns quickly comes,

At sight whereof, our Soldiers bit their thumbs:

For well they wist it was no boot [profit] to fly,

And biding there, there was no boot but die.

165 So that we sent a drum to summon talk,

And came to Parley middle way between,

Monsieur de Licques[32], and Mario did walk,

From foemen's side, and from our side were seen,

Myself, that match for Mario might been:

And Captain Sheffield born of noble race,

To match de Licques, which there was chief in place.

166 Thus met we talked, and stood upon our toes,

With great demands whom little might content,

We craved not only freedom from our foes,

But shipping eke with sails and all full bent,

To come again from whence we first were went:

I mean to come, into our English coast,

Which soil was sure, and might content us most.

167 An old said saw, (and oft seen) that whereas

Thou comest to crave, and doubtst for to obtain,

Iniquum pete (then) ut æquum feras[33],

This had I heard, and sure I was full fain

To prove what profit we thereby might gain:

But at the last when time was stolen away,

We were full glad to play another play.

168 We rendered then with safety for our lives,

Our Ensigns splayed, and managing our arms,

With further faith, that from all kind of gives,

Our soldiers should remain withouten harms:

And sooth to say, these were no false alarms,

For why? they were within twelve days discharged,

And sent away from prison quite enlarged.

169 They were sent home, and we remained still,

In prison pent, but yet right gently used,

To take our lives, it was not Licques will,

(That noble blood, which never man abused,)

Nor ever yet was for his faith accused,

Would God I had the skill to write his praise,

Which lent me comfort in my doleful days.

170 We bode behind, four months or little less,

But whereupon that God he knows not I,

Yet if I might be bold to give a guess,

Then would I say it was for to espy

What ransom we would pay contentedly:

Or else to know how much we were esteemed

In England here, and for what men ydeemed [judged].

171 How so it were, at last we were dispatched,

And home we came as children come from school,

As glad, as fish which were but lately catched,

And straight again were cast into the pool:

For by my fay I count him but a fool,

Which would not rather poorly live at large,

Than rest in prison fed with costly charge.

172 Now have I told a tedious tale in rime

Of my mishaps, and what ill luck I had,

Yet some may say, that all to loud I chime,

Since that in wars my fortune was not bad,

And many a man in prison would be glad,

To fare no worse, and lodge no worse than we,

And eke at last to 'scape and go so free.

173 I must confess that both we were well used,

And promise kept according to contract,

And that nor we, nor Soldiers were abused,

No rigour showed, nor lovely dealing lacked:

I must confess that we were never racked,

Nor forced to do, nor speak against our will,

And yet I count it froward fortune still.

174 A truth it is (since wars are led by chance,

And none so stout but that sometimes may fall,)

No man on earth his honour might advance,

To render better (if he once were thrall)

Why who could wish more comfort at his call,

Than for to yield with ensign full displayed,

And all arms borne in warlike wise for aid?

175 Or who could wish dispatch with greater speed

Than soldiers had which tarried so few days?

Or who could wish, more succour at his need

Than used was to them at all assays?

Bread, meat, and drink, yea wagons in their ways,

To ease the sick and hurt which could not go,

All tane [taken] in wars, are seldom used so.

176 Or who could wish (to ease his captive days)

More liberty than on his faith to rest?

To eat and drink at Baron's board always,

To lie on down, to banquet with the best,

To have all things, at every just request,

To borrow coin, when any seemed to lack,

To have his own, away with him to pack?

177 All this and more I must confess we had,

God save (say I) our noble Queen therefore,

Hinc illæ lachrimæ [hence those tears], there lay the pad,

Which made the strange suspected be the more,

For trust me true, they coveted full sore

To keep our Queen and country fast their friends,

Till all their wars might grow to lucky ends.

178 But were that once to happy end ybrought,

And all stray sheep come home again to fold,

Then look to door: and think the cat is nought,

Although she let the mouse from out her hold:

Believe me now, methinks I dare be bold

To think that if they once were friends again,

We might soon sell all friendship found in Spain.

179 Well these are words and far beyond my reach,

Yet by the way receive them well in worth,

And by the way, let never Licques appeach [impede]

My railing pen, for though my mind abhorreth,

All Spanish pranks: yet must I thunder forth

His worthy praise, who held his faith unstained,

And evermore to us a friend remained.

180 Why said I then, that war is full of woes?

Or sour of taste, to them that know it best?

Who so demands, I will my mind disclose,

And then judge you the burdens of my breast:

Mark well my words and you shall find him blest,

That meddleth least with wars in any wise,

But quiet lives, and all debate defies.

181 For though we did with truth and honour yield,

Yet yielding is always a great disgrace,

And though we made a brave retire in field,

Yet who retires, doth always yield his place:

And though we never did ourselves embase [lower],

But were always at Barons table fed,

Yet better were at home with Barley bread.

182 I leave to tell what loss we did sustain,

In pens, in pay, in wars, and ready wealth,

Since all such trash may gotten be again,

Or wasted well at home by privy stealth:

Small loss hath he which all his living selleth,

To save his life, when other help is none,

Cast up the saddle when the horse is gone.

183 But what I said, I say and swear again,

For first we were in Holland sore [deeply] suspect,

The states did think, that with some filthy gain

The Spanish peers us Captains had infect

They thought we meant our ensigns to erect

In King's behalf: and eke the common sort

Thought privy pay had made us leave our fort.

184 Again, the King's men (only Licques except,

And good Verdugo [34]) thought we were too well,

And that we were but played with in respect,

When as their men in great distress did dwell:

So that with hate their burning hearts did swell,

And bad hang up or drown us everychone [everyone],

These bones we had alway to bite upon.

185 This sauce we had unto our costly fare,

And every day we threatened were indeed,

So that on both sides we must bide the care,

And be mistrust of every wicked deed,

And be revealed, and must ourselves yet feed

With lingering Hope, to get away at last

That self same Hope which tied us there so fast.

186 To make up all, our own men played their part,

And rang a peal to make us more mistrust,

For when they should away from us depart,

And saw us bide, they thought we stayed for lust,

And sent them so in secret to be trust:

They thought and said, thus have our Captains sold

Us silly souls, for groats and glistering gold.

187 Yea, when they were to England safely brought,

Yet talked they still even as they did before:

For slanderous tongues, if once they tattle ought,

With mickle pain will change their wicked lore:

It hath been proved full many days of yore,

That he which once in slander takes delight,

Will seldom frame his words to sound aright.

188 Strange tale to tell, we that had set them free,

And set ourselves on sands for their expense,

We that remained in danger of the tree,

When they were safe, we that were their defence,

With arms, with cost, with deeds, with eloquence:

We that saved such, as knew not where to fly,

Were now by them accused of treachery.

189 These fruits (I say) in wicked wars I found,

Which make me write much more than else I would,

For loss of life, or dread of deadly wound,

Shall never make me blame it though I could,

Since death doth dwell on every kind of mould:

And who in war hath caught a fatal clap,

Might chance at home to have no better hap.

190 So loss of goods shall never trouble me

Since God which gives can take when pleaseth him,

But loss of fame or slandered so to be,

That makes my wits to break above their brim,

And frets my heart, and lames me every limb:

For Noble minds their honour more esteem

Than worldly wights, or wealth, or life can deem.

2. Robert Fruin, The Siege and Relief of Leyden in 1574 (Leiden 1927), p. 14-17.

In the night of May the 25th 1574 the enemy [the Spanish troops] returned

unexpectedly to their old quarters at Leyderdorp. We must allow due

credit to the Spanish general for the skill and energy with which he

invested the town for the second time. It was most important to make

the blockade complete, before the citizens [of Leyden] were on their

guard, and to allow them no time to strengthen the garrison or revictual

the city. In this Valdez was completely successful.

His vanguard under Don Luis Gaytan left Amsterdam by water, and reached

the Rhine by way of the Amstel and the Dracht, past the Oude Wetering

and across the Brasemer Lake. They landed at Leyderdorp in the middle

of the night, and at once began to fortify themselves in the old redoubts.

At early dawn a party of Freebooters from Leyden, who were reconnoitring,

fell into the trap laid for them by Don Luis, and were driven back with

the loss of a few men, among whom was the brave Corporal Andries Allertsz,

the only professional soldier in the service of the town. Convinced that

after this failure no second sortie would be attempted, the Spanish general,

leaving a small force at Leyderdorp, withdrew with the rest along the

Weypoortsche road, by Zoeterwoude, thence by the Stompwyker road to Leidschendam,

and so by Voorburg to the Hague. At all these places he posted a few soldiers

in their old quarters. He met with no resistance anywhere except at the Geestbrug,

where Nicolaas Ruichhaver with a handful of men skirmished with him long enough

to allow the Beggars to escape from the Hague to Delft. On the evening of the

day when he had reached Leyderdorp, Gaytan made his entry into the Hague, where

he was received with acclamation by the populace, whose livelihood was largely

dependent upon the Spanish Government and its officials.

Thus in one day Leyden was invested on the east and south and west sides.

The besieging force was small, and the encircling line incomplete; yet it sufficed to prevent any provisions being brought into the town along the main roads, except by stealth.

The next day, another company of soldiers was seen approaching from the

direction of the Haarlem dunes, by Noordwyk and Rynsburg, towards Valkenburg,

where a month ago the Dutch had begun building a redoubt, which though never

finished, had been garrisoned by five companies of English soldiers.

The approach of the Spanish troops was enough to put them to flight.

They ran along the Ryndyk towards the town, where they begged for admittance

at the Witte Poort.

The following is taken from the memoirs of Bernardino de Mendoza, the famous Spanish general.

3. Bernardino de Mendoza, Comentarios de lo sucedido en las guerras de los Paises-Bajos, desde el año de 1567-1577 (Madrid 1592)

With the firm intention of defending The Hague, even if Valdez couldn't advance to him, Don Luis Gaytan [the Spanish colonel] undertook to supply the town with provisions. After enduring this predicament for three days [May 26-28, 1574], Don Gaytan was informed that Monsieur de Licques [Philippe de Récourt, Baron de Licques] had left Haarlem and was advancing toward the fortress of Valkenburg with Walloon cavalry and infantry, and that De Licques expected support from Don Luis. Therefore Don Gaytan and his troops set out to look for Baron de Licques. The two men met one another, after the [English] rebels had withdrawn from Valkenburg to the village of Ter Wadding- taking position between a ditch (occupied by the soldiers of Leiden), the bridge of Boshuiz and the walls of Leiden. The citizens of Leiden shut their gates to the Englishmen, because they feared spies and traitors among the English troops, and because supplies were so low. They advised the English Captain to move back to the gates of The Hague, where Dutch artillery was posted. When a flag was raised above the city gate, the English should remove themselves from the line of fire and the Dutch artillery would fire on the enemy. However the English were not in agreement with this strategy, instead of complying with it; they chose to surrender to our people. Don Luis Gaytan returned to The Hague and Monsieur de Licques took the English soldiers to Haarlem, where he submitted a report of the events to the Grand Commander [Luis de Requesens].

In view of the fact that the English Queen had categorically stated that England was not at war with Spain and that the English soldiers had aided the rebels without her consent, the majority of the town council voted to have them executed. As it panned out, the Grand Commander determined that the high ranking men be retained in custody impending the payment of their ransom or their exchange for important Spanish prisoners. The other four hundred soldiers[35] were first sent to Brussels from whence they were sent back to England. [36]

Bernardino de Mendoza [Comentarios, xii, 251] says that the lives of the English prisoners were spared at his express solicitation. He was at that juncture sent by the Grand Commander on a mission to Queen Elizabeth [in July 1574], and obtained this boon of his superior as a personal favour to himself.[37]

(John Lothrop Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic, vol. II, 1855, p. 553)

4. Felix E. Schelling, The Life and Writings of George Gascoigne. Boston 1893

The poet records that on 19 March 1573, he set out from Gravesend

To boorde our ship in Quinborough that lay,[38]

setting sail the next morning for Holland, and arriving after all but shipwreck some days later at Brielle [Den Briel]. During these very days of Gascoigne's crossing, De la Marck, the somewhat irregular admiral of William of Orange, forced from his harbourage in English waters by a momentary Spanish ascendency in the counsels of Elizabeth, sailed from Dover, intending to land at Enkbuizen; but, abandoning his original intent, surprised and captured Brielle, April 1, 1572. It is plain then that the party of Gascoigne could not have started out for Brielle, but were diverted hither by stress of weather, or through the treachery of their Dutch pilot, who had deliberately sought to wreck them on a hostile coast. The capture of Brielle was a fortunate accident for this party of Englishmen, as there is nothing to show that they purposed to fight for the King of Spain at this period. Gascoigne's account of the drunkenness and debauchery of the Dutch governor of Brielle and his companions is entirely in keeping with what we learn elsewhere of De la Marck and his fellow "beggars of the sea."

I shall not attempt to follow Gascoigne in his circumstantial account of the various military operations in which he was engaged. (See Gascoigne's poem, The fruites of Warre, Dulce Bellum inexpertis, on this subject.) Indeed it is well-nigh impossible to draw his own

distinction "twixt broyles and bloudie warres." (Stanza 94.) It will therefore be sufficient to call attention to some of the more important occurrences, that we may at least trace the soldier-poet's whereabouts during this period.

It is likely that Gascoigne, holding a captain's commission, was in the detachment of two hundred volunteers sent from Brielle to Flushing under command of Treslong [William de Blois, Seigneur de Treslong] to support the citizens of that town in their rising against Philip. (Stanza 95: "For I have seen full many a Flushing fraye.") We know that there was a large force of English volunteers at Flushing a short time after, under Treslong's successor, Jerome van 't Zeraerts, with whom Gascoigne certainly served. Between this

and August [1572], Gascoigne was engaged in several minor ventures, such as the

"bragge of Bruges" and Aerdenburgh (=Aardenburg).

He also took part in both sieges of Goes or

Tergoes, in the latter under Sir Humphrey Gilbert who commanded the

English forces. (St. 97: “I was again in trench before Tergoes.” — Gascoigne

probably met Sir Humphrey for the first time here, and through him became

acquainted with his half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh.) This second siege began August 26, and was at an end by October 21

[1572], through the brilliant exploit of Mondragon, who relieved the

place by marching three thousand picked men "eight miles across the

drowned lands of the Ooster Schelde from Bergen-op-Zoom" in the dead of

night .

Gascoigne speaks of his subsequent movements as follows : —

99. Since that siege raysde I romed haue about

In Zealand, Holland, Waterland and all,

By sea, by land, by ayre and all throughout

As leaping lottes and chaunce did seem to call.

Now here, now there as Fortune trilde the ball.

Where good Guyllam of Orange badde me be.

After mention of Rammekens, a castle on the island of Walcheren, Gascoigne says that he fought against Mondragon "while he did assaie to lande his men . . . with victuall to

supplie poore Middleburgh." (St. 103.) It appears that a certain Beauvoir went off, whom Gascoigne describes as a commander of the King's side, which was gouverneur of Middelburg next before Mondragon, and that Mondragon in turn was cooped up in Middelburg. All this took place simultaneously with the siege of Haarlem, by which more momentous event it has been obscured.

At this stage of events Gascoigne quarrelled with his colonel [39], for which he assigns the following reasons : -

110. My harte was high, I could not seeme to serue

In regiment where no good rules remayne

Where officers and such as well deserue

Shall be abused by euery page and swayne

Where discipline shall be but deemed vayne,

Where blockes are stridde by stumblers at a strawe,

And where selfe will must stand for martiall lawe.

Gascoigne says of himself that he remained in camp as a private volunteer, after throwing up his "Captaynes charge and eke a Martials state," and removed with the rest to "lande van

Strayne." The war flagging by reason of the winter season, he went to Delft to deliver up his commission to the Prince, or at least obtain furlough for a visit home. In consequence of the Prince's courteous reception of Gascoigne and his earnest if futile effort to effect a reconciliation between Gascoigne and his former colonel, William of Orange receives the highest praises at the hands of the poet, who, whether he understood for what the Dutch were fighting or not, was most earnest in the tribute that he pays to the greatness of their intrepid

leader.

I continue in the words of Octavius G. Gilchrist, Censura Literaria, vol. 3, 1806 : -

While this negociation was meditating, a circumstance occurred which had nearly cost our poet his life. A lady at the Hague (then in the possession of the enemy) with whom Gascoigne had been on intimate terms, had his portrait in her hands (his 'counterfayt' as he calls it), and resolving to part with it to himself alone, wrote a letter to him on the subject, which fell into the hands of his enemies in the camp; from this paper they meant to have raised a report unfavorable to his loyalty; but upon its reaching his hands Gascoigne, conscious of his fidelity, laid it immediately before the Prince, who saw through their design, and gave him passports for visiting the lady at the Hague: the burghers, however, watched his motions with malicious caution, and he was called in derision 'the Green Knight.'

Although William's faith in Gascoigne's integrity is probably quite sufficient evidence of the poet's guiltlessness, there is every reason to believe that the Burgher's distrust of many of the English officers in their employ, was only too well warranted by subsequent traitorous conduct. From what we know of Gascoigne's character and his hearty contempt for the Dutch, it is far from likely that he could have so conducted himself as to have given no offence to his enemies.

Notwithstanding this, Gascoigne again embraced the service of the States and served in the naval battle of Reimerswaal [29 January 1574] "in a Hoy" and in sight of the Prince, who watched the whole engagement.

136. The Prince gan like my fayth and forward will,

Equyppt a Hoye and set hir under sayle,

Wherein I served according to my skill,

My minde was such, my cunning could not quayle,

Withouten bragge of those that did assayle

The foemens fleete which came in good aray,

I put my selfe in formost ranke alway.

137. Three dayes wee fought, as long as water served,

And came to ancor neyghbourlike yfeere,

The Prince himselfe to see who best deserved,

Stoode every day attending on the peere,

And might behold what barke went formost there:

Ill harte had he that would not stoutely fight,

When as his Prince is present still in sight.

138. At last our foes had tidings over lande,

That neare to Bergh their fellowes went to wracke,

On Scheld they mette by Rymerswaell a bande

Of Edellbloets, who put their force abacke,

Lewes de Boyzott[40] did put them there to sacke,

And lost an eye, bicause he would resemble

Dan Julian,[41] whome (there) he made to tremble.

Gascoigne tells us that he was in Middelburg the day before its surrender and passed thence on Mondragon's "promise." (St. 140.) It is not improbable that he was in some capacity engaged in "the parleyings" prior to the surrender of the Spaniards. Middelburg surrendered Feb. 21, 1574, and Gascoigne received of the Prince in consequence his pay, a personal reward of three hundred guilders and a promise of future promotion. (Stanza 141.) Soon after this, re-enforcements coming over from England, Gascoigne was assigned a company under the command of Colonel Edward Chester; and before long was ordered to Valkenburgh, "a fort but new begun" and one of the out-posts of Leyden. [May 1574.]

146. In Valkenburgh (a fort but new begonne)

With others moe I was ordeynde to be,

And farre beforne the worke were half way done,

Our foes set forth our sorie seate to see,

They came in time, but cursed time for me,

They came before the courtine raysed were,

One onely foote above the trenches there.

In the meantime Louis of Nassau, bringing up an army from beyond the Rhine, had suffered defeat at Mookerheyde, May 26, 1574, and a renewal of the siege of Leyden was the immediate result. "Valdez [the Spanish general] lost no time in securing himself the possession of Maeslandsluis, Vlaardingen and the Hague. Five hundred English under command of Colonel Edward Chester, abandoned the fortress of Valkenburg, and fled towards Leyden." - Indeed, Sir Clements Markham (The fighting Veres, 1888) does not hesitate to say that the English under Colonel Chester were disgraced, and that "they surrendered Valkenburg when they might have held out."[42] - According to Gascoigne, the fortress was abandoned because it was impossible to hold it, with so small a garrison, a lack of provision, and insufficient muniment. Moreover, on the arrival of a messenger from Alphen with a statement that this fort, "a stronger place" than Valkenburg, had fallen, a mutiny broke out among the soldiers and the ofificers were compelled to march with them to Leyden, harassed by the enemy all the way.

161. In this retyre three English miles we trodde,

With face to foes and shot as thicke as hayle,

Of whose choyce men full fiftie soules and odde,

We rayed on ground, this is withouten fayle,

Yet of our owne, we lost but three by tale:

Our foes themselves confess they bought full deere,

The hote pursute whiche they attempted there.

162. Thus came we late at last to Leyden walles,

Too late, too soone, and so may we well say,

For notwithstanding all our cries and calles,

They shut their gates and turnd their eares away:

In fine they did forsake us every way,

And badde us shifte to save ourselves apace,

For unto them were fonde to trust for grace.

John Lothrop Motley (Rise of the Dutch Republic, II. 553.) continues : "Refused admittance by the citizens, who now, with reason, distrusted them, they surrendered to Valdez, and were afterwards sent back to England."

Indeed Gascoigne himself admits : -

183 But what I sayde, I say and sweare againe,

For first we were in Hollande sore suspect,

The states did thinke, that with some filthie gaine

The Spainish peeres us Captaines had infect

They thought we ment our ensignes to erect

In Kings behalfe: and eke the common sorte,

Thought privy pay had made us leave our forte.

Worse than that, it seems to have been the general opinion of the English soldiers that they had been sold to the Spanish: an opinion which they hesitated not to avow alike before their

departure and after their arrival in England.(Stanzas 186-187.) Be this as it may, in consequence of the ensuing parley in which Gascoigne and Captain Sheffield were the spokesmen of the English, both soldiers and officers were well used, the latter being sent home, as we have seen, four months thereafter. Gascoigne is loud in his praises of the Spanish captains, who apparently treated him with great courtesy during his short durance, but can not forego the dramatic effect of telling how "the King's men"

with hate their burning hartes did swell

And bad hang up or drowne us euerychone. (St. 184.)

The first siege of Leyden was raised March 21, 1574, but was renewed soon after the defeat and death of Lewis of Nassau at the battle of Mookerheyde, May 26, 1574. As Motley states that Leyden was thoroughly invested again "in the course of a few days," and as the capture of the party that had garrisoned Valkenburg was one of the measures by which Valdez brought about this result, Gascoigne must have been a prisoner by June 1, and was consequently again in England by the following October. (Don Bernardino de Mendoza says that ' the lives of these English prisoners were spared at his express solicitation.' Comentarios, XII. 251. Quoted by Motley, Rise of the Dutch Republic, II. 553, note. )

From a general view of Gascoigne' s career in Holland, it may well be doubted if his earlier services to Mercury are not greater than his later services to Mars: and this despite "the

considerable military reputation" granted him by some of his scholarly biographers. According to the fashion of an age which confounded naval warfare with privateering and war

with petty marauding and adventuring, Gascoigne was a fair specimen of the gentleman adventurer of his day. He was, doubtless, personally brave, but hot-headed and insubordinate,

and as utterly devoid of any knowledge of the broader issues of the quarrel, in which he drew his sword, as was his queen herself or the sorriest of his countrymen that trailed a pike and

starved through the inefficiency or betrayal of their English officers. Gascoigne' s admiration for the personal qualities of the Prince of Orange is too genuine on its face to call for a moment's question, but his gentleman's contempt for the Dutch as a low-born race of Burghers, embittered as it was by their suspicion of treachery, far from unjustifiable in similar

cases, is quite as evident. If Gascoigne was free from the taint of his fellow officers, and there is no proof to show that he was not, he was certainly strong where many men were weak.

It was well known among the English officers, serving in the low countries, that Elizabeth was only temporizing, and that she professed to have no real quarrel with Philip; the Queen's

own policy was fast and loose: little better could be expected of her subjects. Gascoigne was certainly in the worst possible company and judging from the tone of the last portion of The

Fruites of the War, we may, at least, doubt if he did not make a virtue of a necessity in the last act of his military career. Whetstone says - and we may well believe it - that Gascoigne

was "the welthier not a whit" for his services abroad.

NOTES:

[1] Rowland York and William Herle. - Rowland York (c.1553-1588), the ninth of ten sons of Sir John York, in his youth a narrow friend of Oxford, volunteered for the Netherlands under Captain Thomas Morgan in 1572. He embarked at Gravesend on 19 March that year with his two companions, the poet George Gascoigne and William Herle, but their ship was nearly lost on the coast of Holland owing to the incompetence of the Dutch pilot. Reaching the English camp in safety, York took part in August that year in the attack on Goes under Captain (afterwards Sir) Humphrey Gilbert and William of Orange's captain Jerome Tseraerts. - William Herle (died 1588) was a pirate and spy who was imprisoned in the Marshalsea prison in 1571. He became known for his part in Elizabeth I's intelligence network inside the jail, smuggling letters to William Cecil, Lord Burghley, about people involved in the so-called Ridolfi plot, a Roman Catholic plan to assassinate the Queen and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots.

[2] War is sweet to those who have never experienced it. A quote from Pindar, made famous by Erasmus as the title for his meditation on the subject of war.

[3] the brag of Bruges. A marginal conflict in Bruges. Felix E. Schelling (see ahead) writes: "Between May and August [1572], Gascoigne was engaged in several minor ventures, such as the "brag of Bruges" and Aardenburg.

[4] Aerdenburgh. The city of Aardenburg (near Bruges) remained part of the Spanish southern Netherlands.

[5] Tergoes. Goes is a city on Zuid-Beveland, in the province of Zeeland. - In Autumn 1572, Goes, in the Spanish Netherlands, was besieged by Dutch forces with the support of English troops. The siege was relieved in October 1572 by Spanish Tercios, who waded across the Scheldt to attack the besieging forces.

[6] Guillam of Nassau. William I, Prince of Orange (1533-1584), also widely known as William the Silent or more commonly known as William of Orange (Dutch: Willem van Oranje), was the main leader of the Dutch revolt against the Spanish Habsburgs that set off the Eighty Years' War and resulted in the formal independence of the United Provinces in 1581. He was born in the House of Nassau as Count of Nassau-Dillenburg. He became Prince of Orange in 1544 and is thereby the founder of the branch House of Orange-Nassau and the ancestor of the monarchy of the Netherlands.

[7] S. Gyptian's pilgrimage. The pilgrimage of a vagrant or a gipsy.

[8] brake the Bowers. E. Cobham Brewer (Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and the Drama, 1892) interprets: to reject the food provided.

[9] Ramykins. English volunteers helped in the capture of Fort Rammekens (near Middelburg) in August 5, 1573, and in the great sea-fight, when the Zeeland ships attacked the Spanish fleet from Antwerp, with supplies for Middelburg.

[10] Mountdragon. The Spanish general Cristà³bal de Mondragà³n y Mercado (1514-1596) was colonel of the Tercios of Flanders under the Duke of Alba, Luis de Requesens and Alexander Farnese. - See note 15.

[11] Poor Middleburgh. Middelburg is the capital of the province of Zeeland; situated on the central peninsula of the Zeeland province, Midden-Zeeland (consisting of former islands Walcheren, Noord-Beveland and Zuid-Beveland). - Middelburg und Arnemuiden were occupied by the Spanish until the end of January 1574. The towns were held under siege by the Dutch, causing a terrible famine.

[12] ere they sink the sound. OED: sound. A relatively narrow channel or stretch of water, esp. one between the mainland and an island, or connecting two large bodies of water; a strait. Also, an inlet of the sea. (The first quot. may represent the OE. sund 'sea, water'.)

[13] My Colonel and I fell at debate. The man in question is Captain Thomas Morgan.

[14] when Beauvoir fled amain. Philippe de Lannoy, Seigneur de Beauvoir (c.1510-1574). Gascoigne writes Beauvois.

[15] Mountdragon came to town. Cristobal de Mondragon came to Middelburg in November 1573. - See note 10.

[16] My Colonel was now come to the Court. See Colonel Thomas Morgan's letter from 13 November 1573 to Lord Burghley (7.2.1 Oxford and the ships.)

[17] Delf was girt with siege on every side. After the Battle of Delft in October 1573, fought by a small Anglo-Dutch force under Thomas Morgan and an attacking Spanish force under Francisco de Valdez, the Spanish were repelled and forced to retreat. Delft amongst other Dutch towns and cities had been saved and meant that Leiden had better hope of relief. Francisco Valdez (see note 18) informed the Duke of Alba of his defeat showing him that victory could not be achieved without a larger force along with siege artillery. He requested more troops and guns or leave to retire himself from the area with the troops he had; the latter was chosen as Alba refused more men or guns. Julián Romero (see note 24) meanwhile managed to capture Maassluis but an attempt on Delftshaven was repelled. - For his action in helping to repel the Spanish attack on the city the Prince of Orange promoted Edward Chester (see note 27) to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

[18] The Campomaster Valdez. Francisco Valdez (c.1522-1580), a Spanish general. He had command over the besieging imperial forces in the Siege of Leiden (1573-1574).

[19] die groene Hopman. The green Captain. - Gascoigne describes himself as the Green Knight.

[20] Like John Grey's bird that ventured with the best. A proverb.

[21] Equipped a Hoy. A hoy was a small sloop-rigged coasting ship or a heavy barge used for freight, usually with a burthen of about 60 tons. The word derives from the Middle Dutch hoey. - Note: Rigged up and fully furnished.

[22] Rymerswaell. Reimerswaal was granted city rights in 1374. The city was destroyed by repeated floods, and the last citizens left in 1632. Nothing remains. It was located north of the current municipality, on the east end of the Oosterschelde, on land which is now called the Verdronken Land van Reimerswaal (Drowned Land of Reimerswaal).

[23] Lewes de Boyzott. Lodewijk van Boisot (c.1530-1576), Lord of Ruart, the admiral of Flushing. The French Huguenot entered the service of the Dutch. In 1573 he became Admiral of Zeeland and in 1574 he was Lieutenant-Admiral of Holland and Zeeland. On 29 January 1574 he managed to defeat the fleet under the command of Luis de Resquesens y Zúñiga (1528 - 1576). This battle freed the city of Middelburg from the Spanish rule. In 1576 Boisot drowned near Zierikzee during a battle to free this city from the Spanish rule as well.

[24] Dan Julian. Julián Romero de Ibarrola (1518 - 1577) was one of the few common soldiers in the Spanish army to reach the rank of Maestro de Campo. Romero fought in the Siege of Mons (1572), where he nearly succeeded in killing William the Silent, Prince of Orange, in a daring raid against the Dutch camp. He was also present at the Spanish Fury at Naarden and the Siege of Haarlem, where he lost an eye. In 1574, he failed to relieve Middelburg after losing the Battle of Reimerswaal, and in 1576 he was present at the Sack of Antwerp.

[25] Sancho de Avila. Sancho d'Avila (1523-1583) was a Spanish General. In 1574, he was the castellan of Antwerp.

[26] And when Mondrágon might no more endure. On 20 February 1574 the Spanish garrison of Middleburg under the command of Mondragon surrendered.

[27] Edward Chester (died 1579), was the fourth son of Sir William Chester, Lord Mayor of London in 1554-55. Edward Chester's first known military service was as a captain in Gilbert's regiment in Zeeland in 1572. He took over the second draft of the regiment, some three hundred strong, in July. He soon linked up with Gilbert and campaigned with the rest of the regiment thereafter.

Chester raised two companies of his own in 1573, but they were subsumed into Morgan's newly-commissioned regiment. In August 1573 Colonel Morgan's regiment and several Scots companies were repulsing the attack of a detached Spanish division on Delft and other places between Rotterdam and Leyden, in which service Captain Chester highly distinguished himself at the head of two hundred English men-at-arms, for which he was promoted by the Prince of Orange to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. However Orange relieved Colonel Chester of his duties in the middle of October 1573. At a later date, Chester managed to reconcile with the Prince. - In March 1574 he then obtained a commission for a regiment of his own. Though he faced some difficulties, he was able to fill his contract and transport the troops to the Netherlands in March 1574, as the Spanish were aware. But its poor performance outside Leiden in Maye 1574 led to it being disbanded. Chester kept his own company in Dutch pay and kept on good terms with William of Orange and presumably had a good chance of regaining a colonelcy. However he drowned whilst en route from England to Holland in November 1577. (See David J. B. Trim, Fighting Jacob's Wars (Diss. London 2002, p. 378).

[28] In Valkenburgh ... one only foot above the trenches there. The fort to which Gascoigne is referring here is none other than the entrenchment in the vicinity of Katwijk aan den Riijn (Katwijk on the Rhine) where Edward Chester and Gascoigne were situated along with 500 English soldiers. At that point in time building on the fort was still in progress. The English soldiers had run out of money and supplies. When faced by an impending attack of 3000 Spaniards they surrendered the position without putting up a fight. They surrendered to the Spanish at the end of May 1574. - In William Camden's History of the Most Renowned and Victorious Princess Elizabeth (ed. 1688, p. 206) as well as in Clements R. Markham's The Fighting Veres (London 1888, p. 48) they were unjustly admonished for doing so. - "The Capture of Valkenburg" is a myth- because the "English" Valkenburg has nothing whatsoever to do with Valkenburg Castle near Maastricht and Limburg. (The corresponding article on Wikipedia confuses the entrenchment Valkenburg and Valkenburg Castle.)

Sources: Bernardino de Mendoza:Â Commentaires de Bernardino de Mendoça sur les évènements de la guerre des Pays-Bas 1567 - 1577, Vol. 2, Bruxelles 1863, p. 242-243. - Robert Fruin's verspreide geschriften, Deel II, (Gravenhage 1900), 394-397. - Robert Fruin, The Siege and Relief of Leyden in 1574 (1927), p.14-17.

[29] Alphen aan den Rijn, southwest of Leiden.

[30] This Fort [Alphen] from ours was distant ten good miles, / I mean such miles as English measure makes, / Between us both stood Leiden town therewhiles. These lines contain a concise cartographic definition of the position. - See note 28.

[31] At Maeslandsluys we hoped for to sup. Philips of Marnix, lord of Saint-Aldegonde, started to build a defence wall around Maassluis, but before its completion, the Spanish captured the little town in November 1573 and Marnix was taken prisoner.

[32] Monsieur de Licques. Philippe de Récourt, baron de Licques (died 1588), Governor of Haarlem in 1574. - Mario is unknown.

[33] Iniquum pete (then) ut æquum feras. Seek more than what is right so that you may carry off the right amount.

[34] And good Verdugo. Francisco Verdugo (1537-1595), Spanish military commander in the Dutch Revolt, became Maestre de Campo General, in the Spanish Netherlands. He was also the last Spanish Stadtholder of Friesland, Groningen, Drenthe and Overijssel between 1581 and 1594. - Verdugo has been described as a brave, courteous and very experienced soldier, who rose from the rank of musketeer, which he held at the siege of Haarlem, to the governor of Frisia. Nominated Governor of Haarlem in 1573, as an Admiral of the Spanish Fleet he helped to conquer Flanders. In 1576, he became Councillor of State.

[35] The other four hundred soldiers. All the other sources speak of five hundred soldiers.

[36] The original French is as follows.

Don Luis Gaytan approvisonna le château (La Haye), bien résolu à le défendre jusqu'à ce qu'il recût du secours, au cas qu'un événement quelquonque empêchât Valdès de le rejoindre. Il demeura à cette situation pendant trois jours. Alors l'avis lui parvint que M. de Licques était sorti de Harlem; qu'il marchait, ainsi qu'il avait été convenu, avec de la cavalerie et de l'infanterie wallonne contre le fort de Valkenbourg, et qu'il demandait à don Louis le concours de quelques soldats dans le château La Haye, et avec les autres se mit à la recherche du baron de Licques. Il le rencontra au moment où les rebelles, abondonnant le fort, se retiraient sur le village de Wadding, et prenaient position entre une tranchée que tenaient ceux de Leyde, le pont de Boschhuys et les murailles de la ville. Les bourgeois ne voulaient pas les recevoir, craignant le blocus et la disette. Aussie dirent-ils au capitaine et à quelque soldats qu'ils laissèrent entrer que, si les Espagnols les serraient, ils n'avaient qu'à se retirer à la porte de La Haye, qui était le côté où était placé l'artillerie, et, quand ils verraient descendre le drapeau de la porte, de marcher sur le côté droit, parce qu'alors l'artillerie tonnerait contre l'ennemi. Les Anglais ne goutèrent pas ce conseil; ils jugèrent qu'il valait mieux se rendre à nos gens, ce qu'ils firent. Don Luis Gaytan revint alors à la Haye, et M. de Licques, avec les Anglais, se rendit à Harlem, d'où il rendit compte au grand commandeur de ce qui s'était passé; la majorité du conseil proposait de mettre à mort ces prisonniers anglais, puisque la reine d'Angleterre, reconnaissant n'être pas en guerre avec Sa Majesté, déclairait que s'était sans son aveu et son consentement que les Anglais venaient aider les rebelles. (Ces Anglais, qui étaient au nombre de 400, furent d'abord enduits à Harlem; le grand commandeur fit garder les principaux pour servir à la rancon des soldats espagnols prisonniers des ennemies; les autres furent amenés à Bruxelles, puis renvoyés à la reine d'Angleterre.)

(Bernardino de Mendoza: Commentaires de Bernardino de Mendoça sur les évènements de la guerre des Pays-Bas 1567-1577, trad. nouv. par le colonel Guillaume. T. 2, Bruxelles 1863, pp. 242-43.)

[37] Mendoza ... obtained this boon of his superior as a personal favour to himself. At the end of June 1574, Bernardino de Mendoza set out for England. (This was exactly at the time when Oxford arrived on the mainland). He arrived on 12th July in London and was granted an audience with Queen Elizabeth for the 17th July. The Queen and her ministers gave him a truly affable welcome. She did, however protest quite vehemently about the fact that, in The Netherlands, King Philip II had profferred support to Englishmen who were the sword enemies of the crown [Westmoreland etc.] Elizabeth went as far as to say that true friendship could only exist between England and France if Philip were to expel them from the provinces. The ministers went on to say that the British crown was pledged to the cause of Holland and Zeeland's return to Philip's rule. - See: Correspondance de Philippe II sur les affaires des Pays-Bas [1558-1577], T. III, Bruxelles 1858, p. 134.

[38] To boorde our ship in Quinborough that lay. George Gascoigne's Voyage into Holland (written in March 1573) - in: A Hundreth sundrie Flowres (1573)

When from Gravesend in boat I gan to jet

To board our ship in Queenborough that lay,

From whence the very twentieth day we set

Our sails abroad to slice the Salt sea foam,

And anchors weighed gan trust the trustless floud.

[39] Gascoigne quarrelled with his colonel. The man in question is Captain Thomas Morgan.- See note 13.

[40] Lewes de Boyzott. Lodewijk van Boisot. - See note 23.

[41] Dan Julian. Julián Romero de Ibarrola. - See note 24.

[42] they surrendered Valkenburg when they might have held out. See note 28.