- To The Reader

- 1. Shakspere or Shakespeare?

- 2. Shakespeare a Pseudonym?

- 3. Treasure Texts

- 4. Edward de Vere

- 5. Works

- 6. Ben Jonson’s Forgery

- 7. Research for Shake-speare

- 9. Relationship

- 10. Chronology

3.2.2. Willobie his AVISA

WILLOBIE HIS AVISA

Or

The true Picture of a modest Maide, and of a chast and constant wife.

The Willobie enigma is most closely connected with the issue of who wrote Shakespeare’s works. So the solution of the one may be expected to shed light on the other.

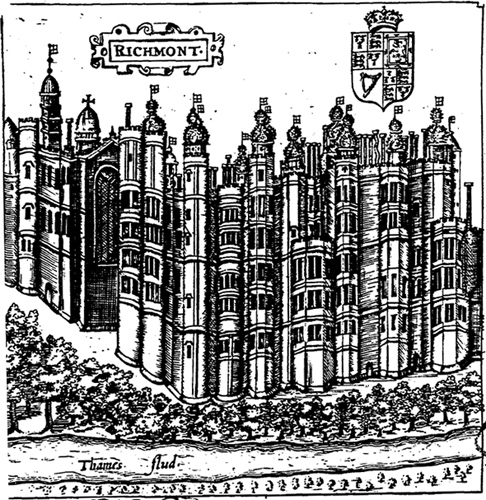

In 1594, the year of the publication of Shakespeare’s Rape of Lucrece, a certain Henry Willobie was the first-ever author to mention the — hyphenated — full name “William Shake-speare” in the preface to his long poem Willobie his AVISA. After Thomas Nashe (1593) and Gabriel Harvey (1593), “Willobie” is the third Elizabethan author to establish a connection between the poet and dramatist Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, and the dramatist William Shake-speare. For a long time, scholars knew neither who was behind the name “Henry Willobie” nor did they know the identity of the female figure who was courted by various suitors; other than the fact that her name was “AVISA”. There was a similar mystery surrounding the suitors, what sort of men were they; were they based on true characters and if so - on whom?

Willobie’s Puritan-tinged narrative can quickly be told. After AVISA has morally castigated four self-important gentlemen (1. “The Nobleman”, 2. “Cavaleiro”, 3. “D. B., a French man” and 4. “D. H. Anglo-Germanus”) and loftily turned down their love-begging posies, she is being wooed by a young man called “H. W. Italo-Hispalensis”, who as a “new actor” seeks counsel from an “old player” called “W. S.”. This “W. S.” throws around Shakespearean phrases, which makes his identification as “William Shake-speare” fairly likely; moreover, it is explicitly made clear he had once himself courted AVISA.

The general groping in the dark about this first record of Shakespeare in a contemporaneous literary comment was effectively ended when professor Barbara de Luna (B. N. de Luna, The Queen Declined, Oxford 1970) published a brilliant historical-philological analysis identifying AVISA as Queen Elizabeth.

“When however, Willobie's poem is considered in the isolation it enjoyed for the first year and a half of its existence, his Avisa's identity flashes up from the page, like an image off a mirror. For if Avisa is not 'Eliza', it is as least remarkable that Willobie should attribute to his heroine - (1) the Queen's personal motto; (2) the crest of her coat of arms; (3) her golden sceptre; (4) her principal heraldic emblems: the Rose, the Falcon, and the Phoenix; (5) 'graces' for parents, designated respectively 'the Rose an Lillie'; (6) personal origins either as a 'love-child' or merely the issue of a love-match; (7) a 'Castle' for a dwelling; and (8) the one clue virtually impossible to dismiss as a chance correlation: five suitors readily identifiable as five of the Queen's best known suitors, treated in nearly the chronological order of their historical originals.” (B. N. de Luna, The Queen Declined, Oxford 1970)

De Luna argues that Henry Willobie had presented Elizabeth’s suitors in chronological order, i.e. Thomas Seymour, King Philip of Spain, Francis Duke of Alençon, Sir Christopher Hatton and the Earl of Essex, the reader is left with the question: “Why on earth is “W.S.” alias “William Shake-speare” included in this illustrious company? Because de Luna was unable to explain this almost unbelievable presence, her historically correct interpretation became too hot to handle by the academic establishment.

(Lately the rather naïve amateur philologist and Stratfordian Michael Mooten identified the incontestable AVISA as being Penelope Devereux thus saving Will Shakspere and impressing us all with a new candidate for the role of “the Dark Lady”. With this Mister Mooten is assuming that Willobie does not take the character AVISA at all seriously, rather presenting her as an adulteress in the guise of a virtuous moralist. An assumption that is absurd even in its very foundations. One could just as easily postulate that the Book of Psalms was written by a Jewish atheist with the intention of ridiculing God. - See notes 17 and 120.)

Barbara de Luna was also able to show that Avisa’s wedding means Elizabeth’s symbolic “wedding” to England, which is why the quick succession of suitors sets in after Avisa’s wedding and why Willobie praises AVISA as the incarnation of chastity. However, to take full profit of De Luna’s analysis in the authorship question it is important to recognize the strong and weak points in De Luna’s analysis. Her arguments about the identity of AVISA and Queen Elizabeth are irrefutable (though she omits to point out that Willobie’s work is embedded in a thirty years old tradition of courting literature [1], would not have reached five issues and would not have been put on the index if the author, shielding behind a pseudonym, had not seriously worried the authorities by the suggestivity of his political allusions [2] .) However, one of the weaknesses of De Luna consist in her attempt to find a concrete historical figure for each suitor Willobie presents, thereby straining the credibility of her analysis, for the author of AVISA (taking cover from possible decipherers behind the name Willobie) was clever enough not to use models too readily recognizable. He wraps his suitors in a shroud of typology. De Luna’s identification of the second suitor “Cavaleiro” as King Philip of Spain is, I think, flatly wrong, while the identification of the “Frenchman” as the Duke d’Alenςon and “Anglo-Germanus” as Sir Christopher Hatton is contestable. On the other hand, Willobie’s depiction of the first suitor, the “Nobleman” is suggestive of Lord Thomas Seymour, though the hints at him do not bear out this identification. On the contrary, the characterization of the fifth suitor (“H. W. Italo-Hispalensis”) is almost unequivocally aimed at the ambitious Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, who in the period between 1592 and 1594 is striving at cementing his power basis (see notes 170 “Like wounded Deer”, and 176 “When woeful Woodbine lies reject”.)

Though Barbara de Luna’s analysis of Willobie his AVISA opens an opportunity window for the Oxfordian approach to the authorship issue, Oxfordians at large have failed to take full advantage of her insights. In order to coherently explain why the Earl of Oxford (alias William Shake-speare) shows up in Willobie’s poem as “old player” and “miserable comforter” of his “friend” Essex it is, however, necessary to consider Shakespeare’s– or Oxford’s – early writings. There is a very strong, though hitherto unnoticed connection between A Hundreth Sundry Flowers from 1573 and Willobie his AVISA from 1594. Nobody seems to have remarked that the solution of the one mystery provides the solution to the other. However, exactly this is the case.

Henry Willobie has carefully observed and copied the procedure of the authors of A Hundreth sundry Flowres (Edward de Vere and George Gascoigne) (See 5.3 The Adventures of Master F. I. and 5.4. Divers excellent devises of sundry gentlemen) - In The Adventures of Master F. I. an editor H. W. publishes the novel “Master F. I.” without the consent of the author. In the case of Willobie his AVISA the editor Hadrian Dorell, of whom absolutely nothing else is otherwise known, publishes the records of a certain “Henry Willobie” without the alleged author’s knowledge. As Master F.I. woos the gentle Mistress Ellinor and expresses his passion in the shape of poems, so the five suitors in Willobie his AVISA court the chaste wife AVISA – the last suitor being Master “H. W. Italo-Hispalensis”. (It cannot be ascribed to chance that Willobie is using the initials “H. W.” and often repeats it insistently.) The authors of The Adventures of Master F.I. and of Willobie his AVISA; both vanish in to thin air- again in both cases there is a second edition whereby the publishers either draw a veil over the intentions of the work or even deny them outright. The reason being that in both works the lady in question was none other than Queen Elizabeth!

And, so our astonishing insight, this is the very reason why “Willobie” puts into the mouth of “H. W.” (whom Barbara de Luna has identified as the Earl of Essex) the words of the young Earl of Oxford. In other words, every time the author has lament “H. W.”, he refers to the poems of the Earl of Oxford, either allusively or sometimes even verbatim (see note 152). The direct or indirect references are to 20 poems of Oxford in A Hundreth sundry Flowres (1573) and 9 more from The Paradyse of daintie Devyses (1576) and manuscript collections.

Below is a list of the poems to which Willobie alludes or from which he quotes:

|

|

III. THE ADVENTURES OF MASTER F. I. (1573)

|

|

|

|

4 |

Of thee dear Dame, three lessons would I learn |

F. I. |

Flowres |

|

16 |

And if I did what then? |

F. I. |

Flowres |

|

|

IV. DIVERS EXCELLENT DEVISES OF SUNDRY GENTLEMEN (1573)

|

|

|

|

20 |

The feeble thread which Lachesis hath spun |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

24 |

I cannot wish thy grief, although thou work my woe |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

25 |

If men may credit give, to true reported fames |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

26 |

Were my heart set on high as thine is bent |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

29 |

The thriftless thread which pamper’d beauty spins |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

30 |

When danger keeps the door of lady beauty’s bower |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

31 |

Thou with thy looks on whom I look full oft |

Si fortunatus infoelix |

Flowres |

|

38 |

The Partridge in the pretty Merlin’s foot |

Spraeta tamen vivunt |

Flowres |

|

40 |

This tenth of March when Aries receiv’d |

Spraeta tamen vivunt |

Flowres |

|

41 |

Now have I found the way to weep and wail my fill |

Spraeta tamen vivunt |

Flowres |

|

42 |

Thy birth, thy beauty, nor thy brave attire |

Spraeta tamen vivunt |

Flowres |

|

44 |

Despised things may live, although they pine in pain |

Spraeta tamen vivunt |

Flowres |

|

45 |

Amid my bale I bath in bliss |

Ferenda Natura |

Flowres |

|

47 |

That self same tongue which first did thee entreat |

Ferenda Natura |

Flowres |

|

51 |

The deadly drops of dark disdain |

Meritum petere grave |

Flowres |

|

55 |

Content thyself with patience perforce |

Meritum petere grave |

Flowres |

|

59 |

The cruel hate which boils within thy burning breast |

Meritum petere grave |

Flowres |

|

63 |

L'Escü d'amour, the shield of perfect love |

Meritum petere grave |

Flowres |

|

|

VII. THE PARADYSE OF DAYNTY DEVISES (1576) |

|

|

|

67 |

If fortune may enforce the careful heart to cry |

[My lucke is losse] RO, LOO. / Balle |

Paradise |

|

71 |

The lively lark did stretch her wing |

E. O. |

Paradise |

|

72 |

A crown of bays shall that man wear |

E. O. |

Paradise |

|

73 |

If care or skill could conquer vain desire |

E. O. |

Paradise |

|

74 |

The trickling tears that fall along my cheeks |

E. O. |

Paradise |

|

77 |

My meaning is to work what wonders love |

E. O. |

Paradise |

|

|

VIII. POEMS 1576-1591 |

|

|

|

90 |

When I was fair and young then favour graced me |

L. of oxforde |

Coningsby / Finet / Cornw. |

|

95 |

How can the feeble fort but yield at last |

Anon. |

Coningsby / Finet |

|

97 |

When that thine eye hath chose the dame |

W. Shakespeare |

Coningsby / Cornwallis / PP |

(See 3.2.2.1 References - and 5.11 Index, Early Works.)

The third suitor; “D.B. A Frenchman”, signs off from his interminable efforts with “Fortuna ferenda. D.B.”. This is a play on Oxford’s signature “Ferenda natura” (The nature that must be endured) that he employs for three poems in Divers excellent devises of sundry gentlemen. Furthermore, Willobie creates an analogy to George Gascoigne’s “The delectable history of sundry adventures passed by Dan Bartholmew of Bath” (in A Hundreth sundrie Flowres – see 3.2.1 Ferenda Natura), because Gascoigne gives the name Ferenda Natura to the woman who brushed him off - and therewith he also means the Queen. (At first Gascoigne praised her and declared her to be a beautiful woman both in mind and body; when she turns away from him the soldier-poet does an about face and turns his praise to admonishment, cancelling their relationship, only to rejoice in her renewed affection and cancel the cancellation.) At the end of the book, Willobie signs off with: “Ever or Never” as did George Gascoigne at the end of A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres.

Just as de Luna demonstrates; Henry Willobie has the fourth and the fifth suitors appear in the form of twin brothers. The fifth suitor is called “H.W. Italo-Hispalensis”. In the main theme “H. W.” figures the Earl of Essex, who fought in Flanders (that is, in the Low Countries) from 1585-1588, in Spain (the ill-fated expedition of the Azores in 1589) and France (before the city of Rouen in 1591) whose supporter in the family crest was the deer. The Italian part of “H. W.” remembers the young Earl of Oxford who travelled through Italy in 1575/76 and who had written The Adventures of Master F[ortunatus]. I[infoelix] in 1573.

The astounding revelation is: Henry Willobie first relates (ironically) a conversation between “W. S.” (William Shake-speare) and “H. W.” (Earl of Essex), subsequently to let speak young Essex in the language of Oxford. That is, Essex repeats the mistakes Oxford has made in his youth — in that he follows the cynical counsel oft he aged Oxford, who speaks to him as Shake-speare. That is (in sober terms) the secret of the “the old player” and “the new actor”.

Therewith “Henry Willobie”, whoever hides behind this name, pokes at the same time fun at Oxford (= Shake-speare) and Essex. Which does not rule out that Willobie might have had sympathy for Oxford, for the satires primarily levelled at Essex and his disquieting political aspirations. The intimate familiarity of Willobie with Oxford’s early writings points to an author of riper age, his invectives against Essex for a member of Walter Raleigh’s circle. Christopher Hill (Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution, 1965, p. 142) proposed Matthew Roydon (c. 1562-1622) as author of Willobie his AVISA.[3] But Roydons three poems are better than Willobie's homemade compilation.

Given that, should we conclude that “H. W.” has nothing to do with Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton (*1573)? “Henry Willobie” cannot have overlooked that the reader would associate the initials “H. W.” with Shakespeare’s friend Henry Wriothesley, to whom “W. S.” had dedicated The Rape of Lucrece in June 1594. And precisely this would have been welcome to Master “Willobie”. That is, though the author of Willobie his AVISA nowhere in his poem targets Southampton (neither was the young man ever relevant as “suitor” of Queen Elizabeth nor had he ever tried to subject her decisions to his will or had ever been a “rejected woobdbine” or a “wounded Deer”), Henry Wriothesley however had become a very prominent figure of Essex’s circle. Southampton had recently turned away from “W. S.” (= Shake-speare = Oxford) to Essex. (Who else than Essex could have been Shakespeare’s “rival”?) Hence, H[enry] W[riothesley] can be regarded as the dumb shadow of “H. W.” (= Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex).

The true Picture of a modest Maid, and of a chaste and constant wife.

In Hexameter verse. The like argument whereof, was never heretofore published.

Read the preface to the Reader before

you enter further.

A vertuous woman is the crown of her husband, but she that maketh him ashamed, is as corruption in his bones. Proverb. 12. 4. [4]

Imprinted at London by John Windet.

1594

To all the constant Ladies & Gentlewomen of England that fear God [5].

Pardon me (sweet Ladies,) if at this present, I deprive you of a just Apology in defence of your constant Chastities, deserved of many of you, and long sithence promised by myself, to some of you: and pardon me the sooner, for that I have long expected that the same should have been performed by some of your selves, which I know are well able, if you were but so wellwilling to write in your own praise, as many men in these days (whose tongues are tipped with poison) are too ready and overwilling, to speak and write to your disgrace. This occasion had been most fit, (publishing now the praise of a constant wife) if I had been but almost ready. But the future time may again reveal as fit a means hereafter for the performance of the same: if so it seem good to him that moderateth all. Concerning this book which I have presumed to dedicate to the safe protection of your accustomed courtesies; if ye ask me for the persons: I am altogether ignorant of them, and have set them down, only as I find them named or disciphered in my author. For the truth of this action, if you enquire, I will more fully deliver my opinion hereafter. Touching the substance of the matter itself, I think verily that the nature, words, gestures, promises, and very quintessence, as it were, is there lively described, of such lewd chapmen as use to entice silly maids and assail the Chastity of honest women. And no doubt but some of you that have beene tried in the like case, (if ever you were tried,) shall in some one part or other acknowledge it to be true. If mine Author have found a Britain Lucretia, or an English Susanna[6], envy not at her praise (good Ladies) but rather endevour to deserve the like. There may be as much done for any of you, as he hath done for his AVISA. Whatsoever is in me, I have vowed it wholy, to the exalting of the glory of your sweet sex, as time, occasion and ability shall permit. In the meantime I rest yours in all dutiful affection, and commend you all to his protection, under whose mercy we enjoy all.

Yours most affectionate,

Hadrian Dorrell[7].

To the gentle & courteous Reader.

It is not long sithence {gentle Reader) that my very good friend and chamber-fellow M. Henry Willobie[8], a young man, and a scholar of very good hope, being desirous to see the fashions of other countries for a time, departed voluntarily to her Majesty’s service. Who at his departure, chose me amongst the rest of his friends, unto whom he reposed so much trust that he delivered me the key of his study, and the use of all his books till his return. Amongst which (perusing them at leisure) I found many pretty & witty conceits, as I suppose of his own doing. One among the rest I fancied so much that I have ventured so far upon his friendship, as to publish it without his consent[9]. As I think it not necessary, to be over-curious in an other man’s labour, so yet something I must say for the better understanding of the whole matter. And therefore, first for the thing itself, whether it be altogether feigned, or in some part true, or altogether true; and yet in most part Poetically shadowed[10], you must give me leave to speak by conjecture, and not by knowledge. My conjecture is doubtfull, and therefore I make you the Judges. Concerning the name of AVISA, I think it to be a feigned name, like unto Ovid’s Corinna; and there are two causes that make me thus to think. First, for that I never heard of any of that name that I remember; and next for that in a void paper rolled up in this book, I found this very name AVISA, written in great letters a pretty distance a sunder, & under every letter a word beginning with the same letter, in this form.

A. V. I. S. A.

Amans. uxor. inviolata. semper. amanda. [loving. wife. uninjured. always. beloved.]

That is in effect, A loving wife that never violated her faith, is always to be beloved. [11] Which makes me conjecture that he minding for his recreation to set out the Idea of a constant wife, (rather describing what good wives should do than registring what any hath done) devised a woman’s name that might fitly express this woman’s nature whom he would aim at: desirous in this (as I conjecture) to imitate a far off, either Plato in his Commonwealth, or More in his Utopia. This my surmise of his meaning, is confirmed also by the sight of other odd papers that I found, wherein he had, as I take it, out of Cornelius Agrippa[12], drawn the several dispositions of the Italian, the Spaniard, the Frenchman, the German, and the Englishman, and how they are affected in love. The Italian dissembling his love, assaileth the woman beloved, with certain prepared wantoness: he praiseth her in written verses, and extolleth her to the Heavens.

The Spaniard is unpatient in burning love, very mad with troubled lasciviousness, he runneth furiously, and with pithyful complaints, bewailing his fervent desire, doth call upon his Lady, and worshippeth her, but having obtained his purpose maketh her common to all men.

The Frenchman endevoureth to serve, he seeketh to pleasure his woman with songs and disports &c.

The German & Englishman being nigher of nature, are inflamed by little and little, but being enamored, they instantly require with art, and entice with gifts &c. Which several qualities are generally expressed by this Author in the two first trials or assaults made by the nobleman, and the lusty Cavalieros, Captains, or Cutters &c. Signifying by this generality that our noblemen, gentlemen, captains and lusty youthes have of late learned the fashions of all these countries, how to sollicit their cause, & court their Ladies, and lovers, & this continueth from the second Canto, to the end of the two and twentieth.

After this he comes to describe these natures again in particular examples more plainly, and beginneth first with the Frenchman under the shadow of these Letters, D. B. from the three and twentieth Canto unto the end of the three and thirtieth. Secondly the Englishman or German, under these Letters, D. H. from the 34. Canto unto the end of the forty-three. Lastly the Spaniard and Italian, who more furiously invadeth his love, & more pathetically endureth than all the rest, from the forty-four Canto to the end of the book. It seems that in this last example the author names himself, and so describeth his own love, I know not, and I will not be curious[13].

All these are so rightly described according to their nature that it may seem the Author rather meant to show what suits might be made, and how they may be answered, than that there hath been any such thing indeed.

These things of the one side lead me to think it altogether a feigned matter, both for the names and the substance, and a plain moral plot, secretly to insinuate, how honest maids & women in such temptations should stand upon their guard, considering the glory & praise that commends a spotless life, and the black ignominy, and foul contempt that waiteth upon a wicked and dissolute behaviour.

Yet of the other side, when I do more deeply consider of it, & more narrowly weigh every particular part, I am driven to think that there is something of truth hidden under this shadow. The reasons that move me are these. First in the same paper where I found the name of AVISA written in great letters, as I said before, I found this also written with the Authors own hand, videlicet [evidently]. Yet I would not have Avisa to be thought a politic fiction, nor a truthless invention, for it may be that I have at least heard of one in the west of England, in whom the substance of all this hath been verified, and in many things the very words specified: which hath endured these and many more, and many greater assaults, yet, as I hear, she stands unspotted, and unconquered.

Again, if we mark the exact descriptions of her birth, her country, the place of her abode; and such other circumstances, but especially the matter and manner of their talks and conferences[14], methinks it a matter almost impossible that any man could invent all this without some ground or foundation to build on.

This enforceth me to conjecture that though the matter be handled poetically, yet there is something under these feigned names and shows that hath been done truly[15]. Now judge you, for I can give no sentence in that I know not. If there be any such constant wife, (as I doubt not but there may be) I wish that there were more would spring from her ashes, and that all were such. Whether my Author knew, or heard of any such I cannot tell, but of mine own knowledge, I dare to swear that I know one, A. D.[16] that either hath, or would, if occasion were so offered, endure these, and many greater temptations with a constant mind and settled heart. And therefore here I must worthily reprehend the envious rage, both of Heathan poets, and of some Christian and English writers, which so far debase the credits and strength of the whole sex that they fear not with lying tongues wickedly to publish that there are none at all that can continue constant, if they be tried. Hereof sprang these false accusing speeches of the old Poets.

Ludunt formosae, casta est, quam nemo rogavit. [Ovid, Amores 1.8]

Fair wenches love to play.

And they are only chaste, whom no man doth assay.

And again

Rara avis in terris, nigroque; simillima cygno,

Foemina casta volat. [Juvenal, Satires, VI, 165]

A rare-seen bird that never flies, on earth ne yet in air.

Like blackish Swan, a woman chaste; if she be young and fair.

This false opinion bred those foul-mouthed speeches of Friar Mantuan [Baptista Mantuanus] that upbraids all women with fleeting unconstancy. This made Ariosto and others to invent, and publish so many lewd and untrue tales of women’s unfaithfulness. And this is the cause that in this book ye shall so often find it objected against AVISA by all her suitors that no woman of what degree soever can be constant if she be much requested, but that the best will yield. But the best is, this common and course conceit is received but only among common, lewd, & careless men, who being wicked themselves, give sentence of all others, according to the loose and lawless humours wherewithal they feel their own straying and wandering affections to be infected. For they forsooth, because in divers and sundry places, (as they often wickedly boast) they may for an Angel and a great deal less, have hired nags to ride at their pleasure, such as make a sinful gain of a filthy carcass; because in other countries, where stews and brothelhouses are winked at, they see oftentimes, the fairest and not the meanest flock to the fellowship of such filthy freedom, Think presently, that it is but a money matter, or a little entreaty, to overthrow the chastity of any woman whatsoever. But if all women were indeed such as the woman figured under the name of AVISA either is, or at least is supposed to be, they should quickly restore again their ancient credit and glory which a few wicked wantons have thus generally obscured[17]. In the twenty and seven Canto, I find how D. B. persuadeth with A[visa] that it is little sin or no fault to love a friend besides her husband. Whereupon, inquiring more of the matter I have heard some of the occupation verify it for a truth: That among the best sort, they are accompted very honest women in some cities now that love but one friend besides their husband, and that it is thought amongst them a thing almost lawful. If this be true, (as I hardly think it to be true, because wicked men fear not to report any untruths) but if it be true, I fear least the ripeness of our sin cry to the Lord for vengeance against us that tremble not at the remembrance of God’s judgements that have bound a heavy curse & woe upon the back and conscience of them that speak good of evil, and evil of good. That is, such as are grown to that point that they are no longer ashamed of their sin, nor care for any honesty, but are become wilfully desperate in the performance of all kind of impiety.

But I leave this to the godly preachers to dilate more amply. And to return to my purpose, although I must confess that of all sorts of people, there have been and will be still some loosely and lewdly given, yet this can be no excuse to lavish tongues, to condemn all generally. For, I dare to venture my hand, and my head upon this point that, let the four moral virtues be in order set down

Prudence,

Fortitude,

Temperance,

Justice

and let the holy scriptures be searched from the beginning to the end, & let all the ancient histories both ecclesiastical and profane be thoroughly examined, and there will be found women enough that in the performance of all these virtues, have matched, if not overmatched men of every age, which I dare myself, to verify in their behalfs upon the venture and losing of my credit, if I had time and leisure. Among infinite numbers to give you a taste of one or two: for wisdom, and Justice, what say you to Placilla wife to the Emperor Theodosius? She was wont every day in her own person, to visit the sick, the poor, and the maimed: And if at any time she saw the Emperor declining from Justice to any hard course, she would bid him Remember himself, from whence he came, & what he was, in what state he had been, and in what state he was now; which if he would do, he should never wax proud nor cruel, but rather humble, merciful and just.

For temperance, how say you to the wife of one Pelagius, of Laodicea which being young herself, and married to a young and lusty man, was yet notwithstanding contented willingly to forbear carnal pleasure, during her whole life. I bring not this woman’s example, for any liking I have to her fact, being lawfully married, but rather, against the curious carpers [cavillers] at women’s strength, to prove that some women have done that which few men can do.

For Fortitude and temperance both, I find that in Antioch, there was a noble woman with her two daughters, rather than they would be defloured, cast themselves allwillingly into a great river, and so drowned themselves.

And also that in Rome there was a Senator’s wife, who when she heard that there were messengers sent from Maxentius the tyrant, to bring her unto him, perforce, to be ravished of him; and seeing that her husband was not of ability and power to defend her, she used this policy. She requested that they would give her leave to put on some better apparel & to attire herself more decently: which being granted, and she gotten into a chamber by herself, she took a sword and pierced herself to the heart, rather than she would be counted the Emperor’s whore.

By this may be seen what might be said in this argument, but leaving this to some other time, or some other better able; I return to my author.

For the persons & matter, you have heard my conjecture, now for the manner of the composition, disposition, invention, and order of the verse, I must leave every man’s sense to himself, for that which pleaseth me, may not fancy others. But to speak my judgement, the invention, the argument, and the disposition, is not common, nor (that I know) ever handled of any man before in this order. For the composition and order of the verse: Although he fly not aloft with the wings of Astrophel nor dare to compare with the Arcadian shepherd, or any way match with the dainty Faery Queen; yet shall you find his words and phrases, neither Trivial nor absurd, but all the whole work, for the verse, pleasant, without hardness, smooth without any roughness, sweet without tediousness, easy to be understood, without harsh absurdity: yielding a gracious harmony everywhere, to the delight of the Reader.

I have christened it by the name of Willoby his Avisa: because I suppose it was his doing, being written with his own hand. How he will like my boldness, both in the publishing, and naming of it, I know not. For the encouraging and helping of maids and wives to hold an honest and constant course against all unhonest and lewd temptations, I have done that I have done[18]. I have not added nor detracted anything from the work itself, but have let it pass without altering anything: Only in the end I have added to fill up some void paper certain fragments and ditties, as a resolution of a chaste and constant wife, to the tune of Fortune, and the praise of a contented mind, which I found wrapped altogether with this, and therefore knew not whether it did anyway belong unto this or not.

Thus leaving to trouble your patience with farther delays, I commit you to the good government of God’s spirit. From my chamber in Oxford this first of October.

Hadrian Dorrell.

Abell Emet in commendation of Willobie’s Avisa.

To Willobie, you worthy Dames, yield worthy praise,

Whose silver pipe so sweetly sounds your strange delays,

Whose lofty style, with golden wings remounts your fame,

The glory of your Princely sex, the spotless name:

O happy wench, who so she be if any be,

That thus deserv’d thus to be praised by Willobie,

Shall I believe, I must believe, such one there is,

Well hast thou said, long mayst thou say, such one there is,

If one there be, I can believe there are no more,

This wicked age, this sinful time breeds no such store:

Such silver mints, such golden mines who could refuse?

Such offers made and not receiv'd, I greatly muse.

Such deep deceit in friendly shows, such tempting fits,

To still withstand, doth pass the reach of women’s wits:

You Country maids, Paean nymphs rejoice and sing,

To see from you a chaste, a new Diana spring:

At whose report you must not fret, you may not frown,

But rather strive by due desert for like renown,

Her constant faith in hot assay hath won the game,

Whose praise shall live, when she is dead with lasting fame:

If my conceit from stranger’s mouth may credit get,

A braver Theme, more sweetly pend, was never yet.

Abell Emet.[19]

In praise of Willobie his Avisa, Hexameton to the Author.[20]

In Lavin Land though Livy boast,

There hath been seen a Constant dame[21]:

Though Rome lament that she have lost

The Garland of her rarest fame,

Yet now we see that here is found

As great a Faith [trust] in English ground[22].

Though Collatin have dearly bought,

To high renown, a lasting life,

And found that most in vain have sought

To have a Fair, and Constant wife,

Yet Tarquin plucked his glistering grape,

And Shake-speare paints poor Lucrece rape[23].

Though Susan shine in faithful praise

As twinkling Stars in Crystal sky,

Penelop's fame though Greeks do raise,

Of faithful wives to make up three:

To think the Truth, and say no less,

Our Ávisa shall make a mess[24].

This number [four] knits so sure a knot,

Time doubts that she shall add no more,

Unconstant Nature hath begot

Of Fleeting Femes such fickle store:

Two thousand years have scarcely seen

Such as the worst of these have been.

Then Avi-Susan join in one,

Let Lucres-Avis be thy name,

This English Eagle soars alone[25],

And far surmounts all others fame:

Where high or low, where great or small,

This Britain Bird out-flies them all.

Were these three happy that have found

Brave Poets to depaint their praise?

Of Rural Pipe, with sweetest sound,

That have been heard these many days:

Sweet wylloby his AVIS blessed[26],

That makes her mount above the rest.

Contraria Contrariis: Vigilantius: Dormitanus.[27]

WILLOBIE HIS AVISA,

OR

The true picture of a modest Maid, and of a chaste and constant wife.[28]

CANT. I.

Let martial men of Mars his praise

Sound warlike trump: let lust-led youth

Of wicked love write wanton lays,

Let shepherds sing their sheep-coat’s ruth:

The wiser sort confess it plain

That these have spent good time in vain.

My sleepy Muse that wakes but now,

Nor now had waked if one had slept[29],

To virtue’s praise hath passed her vow

To paint the Rose which grace hath kept:

Of sweetest Rose that still doth spring,

Of virtue’s bird my Muse must sing.[30]

The bird that doth resemble right

The Turtle’s faith in constant love[31],

The faith that first her promise plight [assure],

No change, nor chance could once remove:

This have I tried; This dare I trust,

And sing the truth, I will, I must.

Afflicted Susan’s spotless thought,

Entic’d by lust to sinful crime,

To lasting fame her name hath brought,

Whose praise encounters endless time:

I sing of one whose beauty’s war

For trials pass Susanna’s far.

The wandering Greek’s renowned mate[32]

That still withstood such hot assays

Of raging lust; whose doubtful state

Sought strong refuge from strange delays:

For fierce assaults and trials rare

With this my Nymph may not compare.

Hot trials try where Gold be pure,

The Diamond daunts the sharpest edge,

Light chaff fierce flames may not endure,

All quickly leap the lowly hedge:

The object of my Muse hath pass’d

Both force and flame, yet stands she fast.

Though Eagle-eyed this bird appear,

Not blush’d at beams of Phœbus’ rays:

Though Falcon wing’d to pierce the air[33]

Whose high-plac’d heart no fear dismays:

Yet sprang she not from Eagles nest,

But Turtle-bred loves Turtle best.

At wester side of Albion’s Ile,

Where Austin pitched his Monkish tent[34],

Where Shepherds sing, where Muses smile,

The graces met with one consent[35]

To frame each one in sundry part

Some cunning work to show their art.

First Venus fram’d a luring eye[36],

A sweet aspect, and comely grace;

There did the Rose and Lily lie

That bravely decked a smiling face,

Here Cupid’s mother bent her will,

In this to show her utmost skill.

Then Pallas gave a reaching head

With deep conceits, and passing wit,

A settled mind, not fancy-led,

Abhorring Cupid’s frantic fit,

With modest looks, and blushing cheeks,

A filed tongue which none mislikes.[37]

Diana decked the remnant parts

With feature brave that nothing lack,

A quiver full of piercing Darts,

She gave her hanging at her back;

And in her hand a Golden shaft

To conquer Cupid’s creeping craft.[38]

This done they come to take the view

Of novel work, of peerless frame;

Amongst them three contention grew,

But yet Diana gave the name:

‘Avisa shall she called be,

The chief attendant still on me.’

When Juno view'd her luring grace,

Old Juno blushed to see a new,

She fear'd least Jove would like this face

And so perhaps might play untrue[39];

They all admir'd so sweet a sight,

They all envied so rare a wight.

When Juno came to give her wealth

(Which wanting beauty, wants her life),

She cried, this face needs not my pelf,

Great riches sow the seeds of strife:

I doubt not, some Olympian power

Will fill her lap with Golden shower[40].

This jealous Juno faintly said,

As half misdeeming wanton Jove,

But chaste Diana took the maid,

Such new-bred qualms quite to remove:

O jealous envy, filthy beast,

For envy Juno gave her least[41].

In lieu [instead] of Juno's Golden part

Diana gave her double grace;

A chaste desire, a constant heart,

Disdain of love in fawning face:

A face, and eye that should entice,

A smile that should deceive the wise[42].

A sober tongue that should allure,

And draw great numbers to the field[43];

A flinty heart that should endure

All fierce assaults, and never yield,

And seeming oft as though she would;

Yet farthest off when that she should.

Can filthy sink yield wholesome air,

Or virtue from a vice proceed?

Can envious heart, or jealous fear

Repel the things that are decreed?

By envy though she lost her thrift,

She got by grace a better gift.

Not far from thence there lies a vale,

A rosy vale in pleasant plain[44];

The Nymphs frequent this happy dale,

Old Helicon revives again:

Here Muses sing, here Satyrs play,

Here mirth resounds both night and day.

At East of this a Castle stands,

By ancient shepherds built of old,

And lately was in shepherds’ hands,

Though now by brothers bought and sold[45],

At west side springs a Crystal well;

There doth this chaste Avisa dwell.

And there she dwells in public eye,

Shut up from none that list to see;

She answers all that list to try,

Both high and low of each degree[46]:

But few that come, but feel her dart,

And try her well ere they depart.

They tried her hard in hope to gain,

Her mild behaviour breeds their hope,

Their hope assures them to obtain,

Till having run their witless scope;

They find their vice by vertue crossed,

Their foolish words, and labour lost.

This strange effect that all should crave,

Yet none obtain their wrong desire,

A secret gift that nature gave

To feel the frost amidst the fire:

Blame not this Dian’s Nymph too much,

Sith God by nature made her such[47].

Let all the graces now be glad

That fram'd a grace that passed them all,

Let Juno be no longer sad;

Her wanton Jove hath had a fall;

Ten years have tried this constant dame[48],

And yet she holds a spotless fame.

Along this plain there lies a down,

Where shepherds feed their frisking flock;

Her Sire the Major of the town,

A lovely shoot of ancient stock[49];

Full twenty years she lived a maid,

And never was by man betray’d[50].

At length by Juno's great request,

Diana loath, yet gave her leave

Of flowring years to spend the rest

In wed-lock band; but yet receive,

Quod she, this gift; Thou virgin pure,

Chaste wife in wed-lock shalt endure. [51]

O happy man that shall enjoy

A blessing of so rare a prize[52],

That frees the heart from such annoy,

As often doth torment the wise:

A loving wife unto her death,

With full assurance of her faith.

When flying fame began to tell,

How beauty’s wonder was returned

From country hills in town to dwell,

With special gifts and grace adorned

Of suitor’s store there might you see;

And some were men of high degree[53].

But wisdom wield her chose her mate,

If that she lov'd a happy life

That might be equal to her state

To crop the sprigs of future strife;

Where rich in grace, where sound in health,

Most men do wed, but for the wealth.

Though jealous Juno had denied

This happy wench great store of pelf:

Yet is she now in wedlock tide,

To one that loves her as himself;

So thus they live, and thus they love,

And God doth bless them from above.

This rare seen bird, this Phœnix sage[54]

Yields matter to my drowsy pen,

The mirror of this sinful age

That gives us beasts in shapes of men;

Such beasts as still continue sin,

Where age doth leave, there youths begin.

Our English soil to Sodom’s sink

Excessive sin transform’d of late,

Of foul deceit the loathsome link

Hath worn all faith clean out of date;

The greatest sins mongst greatest sort,

Are counted now but for a sport.

Old Asa’s grandam is restor'd;

Her groovy Caves are new refined:[55]

The monster Idol is ador'd

By lusty dames of Maaka's kind[56]:

They may not let this worship fall,

Although they lease their honours all.

Our Moab Cozbi’s cast no fear

To jet in view of every eye[57]

Their gainless games they hold so dear,

They follow must, although they die.

For why? the sword that Phineas wore,

Is broken now, and cuts no more.[58]

My tender Muse that never tried

Her jointed wings till present time,

At first the peerless bird espied

That mounts aloft, devoid of crime;

Though high she soar, yet will I try,

Where I her passage can descry.

Her high conceits, her constant mind;

Her sober talk, her stout denies;

Her chaste advise, here shall you find;

Her fierce assaults, her mild replies,

Her daily fight with great and small,

Yet constant virtue conquers all[59].

The first that says to pluck the Rose,

That scarce appear'd without the bud,

With Gorgeous shows of golden gloze

To sow the seeds that were not good:

Suppose it were some nobleman

That tried her thus, and thus began.

The first trial of Avisa, before she was married, by a Nobleman[60]:

under which is represented a warning to all young maids

of every degree that they beware of the alluring

enticements of great men.

CANT. II

NOB.

Now is the time if thou be wise,

Thou happy maid, if thou canst see

Thy happiest time, take good advise;

Good fortune laughs, be ruled by me:

Be ruled by me, and here's my faith,

No Gold shall want thee till thy death.

Thou knowest my power, thou seest my might,

Thou knowest I can maintain thee well,

And help thy friends unto their right;

Thou shalt with me for ever dwell:

My secret friend thou shalt remain,

And all shall turn to thy great gain.

Thou seest thy parents mean estate,

That bars the hope of greater chance;

And if thou prove not wise too late,

Thou mayst thyself, and thine advance;

Repulse not fondly this good hap

That now lies offered in thy lap.

Abandon fear that bars consent,

Repel the shame that fears a blot,

Let wisdom weigh what faith is meant,

That all may praise thy happy lot;

Think not I seek thy life’s disgrace;

For thou shalt have a Lady’s place.

Thou art the first my fancy chose,

I know my friends will like it well;

This friendly fault to none disclose,

And what thou thinkst, blush not to tell:

Thou seest my love, thou know'st my mind,

Now let me feel, what grace I find.

CANT. III

AVISA

Your Honour’s place, your riper years,

Might better frame some graver talks:

Midst sunny rays this cloud appears;

Sweet Roses grow on prickly stalks[61]:

If I conceive what you request,

You aim at that I most detest.

My tender age that wants advice,

And craves the aid of sager guides,

Should rather learn for to be wise,

To stay my steps from slippery slides,

Than thus to suck, than thus to taste

The poisoned sap that kills at last.

I wonder what your wisdom meant,

Thus to assault a silly maid:

Some simple wench might chance consent,

By false resembling shows betrayed:

I have by grace a native shield[62]

To lewd assaults that cannot yield.

I am too base to be your wife,

You choose me for your secret friend[63];

That is to lead a filthy life,

Whereon attends a fearful end;

Though I be poor[64], I tell you plain,

To be your whore I flat disdain.

Your high estate, your silver shrines,

Replete with wind and filthy stink;

Your glittering gifts, your golden mines

May force some fools perhaps to shrink:

But I have learned that sweetest bait

Oft shrouds the hook of most deceit.

What great good hap, what happy time

Your proffer brings, let yielding maids

Of former age, which thought to climb

To highest tops of earthly aids,

Come back a while, and let them tell,

Where wicked lives have ended well.

Shore’s wife, a Prince’s secret friend,

Fair Rosamond, a Kings delight[65]:

Yet both have found a ghastly end,

And fortune’s friends felt fortune’s spite:

What greater joys could fancy frame

Yet now we see their lasting shame.

If princely palace have no power

To shade the shame of secret sin,

If black reproach such names devour,

What gain, or glory can they win:

That tracing tracts of shameless trade

A hate of God, and man are made?

This only virtue must advance

My mean estate to joyful bliss:

For she that sways dame virtue’s lance,

Of happy state can never miss,

But they that hope to gain by vice,

Shall surely prove too late unwise.

The root of woe is fond desire

That never feels herself content:

But wanton wing'd will needs aspire

To find the thing she may lament:

A courtly state, a Lady’s place,

My former life will quite deface[66].

Such strange conceits may hap prevail

With such as love such strong deceits,

But I am taught such qualms to quail,

And flee such sweet alluring baits:

The witless Fly plays with the flame,

Till she be scorched with the same[67].

You long to know what grace you find,

In me, perchance, more than you would,

Except you quickly change your mind,

I find in you less than I should:

Move this no more, use no reply,

I'll keep mine honour till I die.

Cant. IIII.

NOB.

Alas, good soul, and will ye so?

You will be chaste Diana’s mate;

Till time have wove the web of woe,

Then to repent will be too late:

You show yourself so fool-precise

That I can hardly think you wise[68].

You sprang belike from Noble stock

That stand so much upon your fame[69],

You hope to stay upon the rock

That will preserve a faultless name:

But while you hunt for needless praise,

You loose the prime of sweetest days.

A merry time when country maids

Shall stand (forsooth) upon their guard [attention];

And dare control the Courtier’s deeds

At honour’s gate that watch and ward;

When Milkmaids shall their pleasures fly,

And on their credits must rely[70].

Ah, silly wench, take not a pride,

Though thou my raging fancy move;

Thy betters far, if they were tried,

Would fain accept my proffered love:

T’was for thy good, if thou hadst wist,

For I may have whom ere I list.

But here thy folly may appear,

Art thou preciser than a Queen[71]:

Queen Joan of Naples did not fear,

To quite men’s love with love again:

And Messalina, t’is no news,

Was daily seen to haunt the stews.

And Cleopatra, prince of Nile,

With more than one was wont to play:

And yet she keeps her glorious style,

And fame that never shall decay:

What need’st thou then to fear of shame,

When Queens and Nobles use the same?

CANT. V.

AVISA.

Needs must the sheep strike all awry

Whose shepherds wander from their way:

Needs must the sickly patient die

Whose Doctor seeks his life’s decay:

Needs must the people well be taught

Whose chiefest leaders all are naught.

Such lawless guides God’s people found,

When Moab maids allur’d their fall;

They sought no salve to cure this wound,

Till God commands to hang them all[72]:

For wicked life a shameful end

To wretched men the Lord doth send.

Was earth consum’d with wreakful waves?

Did Sodom burn and after sink?

What sin is that which vengeance craves,

If wicked lust no sin we think?

O blind conceits! O filthy breath!

That draws us headlong to our death.

If death be due to every sin,

How can I then be too precise?

Where pleasures end if pain begin,

What need have we then to be wise?

They weave indeed the web of woe

That from the Lord do yield to go.

I will remember whence I came,

I hunt not for this worldly praise,

I long to keep a blameless fame,

And constant heart gainst hard assays:

If this be folly, want of skill,

I will remain thus foolish still.

The blindfold rage of heathen Queens,

Or rather queens that know not God,

God’s heavy judgements tried since,

And felt the weight of angry rod:

God save me from that Sodom’s cry

Whose deadly sting shall never die.

[Cant. VI - XI][73]

CANT. XII

NOB. Furens

Thou beggar’s brat, thou dunghill mate,

Thou clownish spawn, thou country gill,

My love is turned to wreakful hate,

Go hang, and keep thy credit still,

Gad where thou list, aright or wrong,

I hope to see thee beg, err long.

Was this great offer well refus'd,

Or was this proffer all too base?

Am I fit man to be abus'd

With such disgrace by flattering gaze?

On thee or thine, as I am man,

I will revenge this if I can.

Thou think'st thyself a peerless prize,

And peevish pride that doth possess

Thy heart; persuades that thou art wise,

When God doth know ther's nothing less:

T'was not thy beauty that did move

This fond affect, but blinded love.

I hope to see some country clown

Possessor of that fleering face,

When need shall force thy pride come down,

I'le laugh to see thy foolish case:

For thou that think'st thyself so brave,

Wilt take at last some paltry knave.

Thouself will gig that doth detest

My faithful love, look to thy fame,

If thou offend, I do protest,

I 'll bring thee out to open shame:

For sith thou fain'st thyself so pure,

Look to thy leaps that they be sure.

I was thy friend, but now thy foe,

Thou hadst my heart, but now my hate,

Refusing wealth, God send thee woe,

Repentance now will come too late,

That tongue that did protest my faith,

Shall wail thy pride, and wish thy death.

CANT. XIII

AVISA

Yea so I thought, this is the end

Of wandring lust, resembling love,

Was’t love or lust that did intend

Such friendless force as you did move?

Though you may vaunt of happier fate,

I am content with my estate.

I rather choose a quiet mind,

A conscience clear from bloody sins

Than short delights, and therein find

That gnawing worm that never lins [ceases].

Your bitter speeches please me more

Than all your wealth, and all your store.

I love to live devoid of crime,

Although I beg, although I pine,

These fading joys for little time,

Embrace who list, I here resign,

How poor I go, how mean I fare,

If God be pleas'd, I do not care.

I rather bear your raging ire,

Although you swear revengement deep,

Than yield for gain to lewd desire,

That you might laugh, when I should weep:

Your lust would like but for a space,

But who could salve my foul disgrace?

Mine ears have heard your taunting words

Of yielding fools by you betrayed

Amongst your mates at open boards,

Know’st such a wife? know’st such a maid?

Then must you laugh, then must you wink,

And leave the rest for them to think.

Nay yet welfare the happy life,

That need not blush at every view:

Although I be a poor man’s wife,

Yet then I ‘le laugh as well as you:

Then laugh as long as you think best,

My fact shall frame you no such jest.

If I do hap to leap aside,

I must not come to you for aid,

Alas now that you be denied,

You think to make me soar afraid;

Nay watch your worst, I do not care,

If I offend, prey do not spare.

You were my friend, you were but dust,

The Lord is he, whom I do love,

He hath my heart, in him I trust,

And he doth guard me from above:

I weigh not death, I fear not hell,

This is enough, and so farewell[74].

THE SECOND TEMPTATION OF AVISA

after her marriage by Ruffians, Roisters, young

Gentlemen, and lusty Captains[75], which all

she quickly cuts off.

CANT. XIIII

CAVEILEIRO

Come lusty wench, I like thy looks,

And such a pleasant look I love,

Thine eyes are like to baited hooks

That force the hungry fish to move:

Where nature granteth such a face,

I need not doubt to purchase grace.

I doubt not but thy inward thought

Doth yield as fast as doth thine eye;

A love in me hath fancy wrought,

Which work you cannot well deny:

From love you cannot me refrain,

I seek but this, love me again.

And so thou dost, I know it well,

I knew it by thy side-cast glance,

Can heart from outward look rebel?

Which yesternight I spied by chance:

Thy love (sweet heart) shall not be lost,

How dear a price so ever it cost.

Ask what thou wilt, thou know'st my mind,

Appoint the place, and I will come,

Appoint the time, and thou shalt find,

Thou canst not fare so well at home:

Few words suffice, where heart’s consent,

I hope thou know'st, and art content.

Though I a stranger seem as yet,

And seldom seen before this day,

Assure thyself that thou mayst get

More knacks by me than I will say:

Such store of wealth as I will bring,

Shall make thee leap, shall make thee sing[76].

I must be gone, use no delay,

At six or seven the chance may rise,

Old gamesters know their vantage play,

And when t'is best to cast the dice:

Leave ope your point, take up your man,

And mine shall quickly enter than.

CANT. XV

AVISA

What now? what news? new wars in hand?

More trumpets blown of fond conceits?

More banners spread of folly’s band?

New Captains coining new deceits?

Ah woe is me, new camps are plast [placed],

Whereas I thought all dangers past.

O wretched soul, what face have I,

That cannot look, but some misdeem?

What sprite doth lurk within mine eye,

That kindles thoughts so much unclean?

O luckless feature never blessed,

That sow'st the seeds of such unrest.

What wandring fits are these that move

Your heart, enraged with every glance,

That judge a woman straight in love,

That wields her eye aside by chance:

If this your hope, by fancy wrought,

You hope on that I never thought.

If nature give me such a look,

Which seems at first unchaste or ill,

Yet shall it prove no baited hook

To draw your lust to wanton will:

My face and will do not agree,

Which you in time (perhaps) may see.

If smiling cheer and friendly words,

If pleasant talk such thoughts procure,

Yet know my heart no will affords

To scratching kites to cast the lure:

If mild behaviour thus offend,

I will assay this fault to mend.

You plant your hope upon the sand

That build on women’s words, or smiles;

For when you think yourself to stand

In greatest grace, they prove but wiles:

When fixed you think on surest ground,

Then farthest off they will be found.

CANT. XVI.[77]

AVISA

You speak of love, you talk of cost,

Is’t filthy love your worship means?

Assure yourself your labour’s lost[78];

Bestow your cost among your queans [harlots] [79]:

You left not here, nor here shall find

Such mates as match your beastly mind.

You must again to Coleman hedge [hatch][80],

For there be some that look for gain,

They will bestow the Frenchman’s badge[81]

In lieu of all your cost and pain:

But Sir, it is against my use,

For gain to make my house a stews.

What have you seen, what have I done

That you should judge my mind so light,

That I so quickly might be won

Of one that came but yesternight?

Of one I wist not whence he came,

Nor what he is, nor what’s his name? [82]

Though face do friendly smile on all,

Yet judge me not to be so kind

To come at every Faulkner’s call,

Or wave aloft with every wind:

And you that venture thus to try

Shall find how far you shoot awry.

And if your face might be your judge,

Your wanny cheeks, your shaggy locks

Would rather move my mind to grudge

To fear the piles, or else the pocks:[83]

If you be mov’d to make amends [retribution],

Pray keep your knacks for other friends.

You may be walking when you list,

Look there’s the door, and there’s the way,

I hope you have your market [business] miss’d,

Your game is lost, for lack of play:

The point is close, no chance can fall

That enters there, or ever shall.

[Cant. XVII - XX][84]

CANT. XXI

CAVELEIRO

Had I known this when I began,

You would have used me as you say,

I would have took you napping than,

Nor give you leave to say me nay:

I little thought to find you so,

I never dreamt, you would say no.

Such self like wench I never met,

Great cause have I thus hard to crave it,

If ever man have had it yet,

I sworen have that I will have it:

If thou didst never give consent,

I must perforce be then content.

If thou wilt swear that thou hast known

In carnal act no other man:

But only one, and he thine own,

Since man and wife you first began:[85]

I 'le leave my suit, and swear it true,

Thy like indeed I never knew.

CANT. XXII

AVISA

I told you first what you should find,

Although you thought I did but jest,

And self affection made you blind

To seek the thing I most detest;

Besides his host, who takes the pain

To reckon first, must count again.

Your rash swore oath you must repent,

You must beware of headlong vows;

Excepting him whom free consent

By wedlock words hath made my spouse:[86]

From others yet I am as free

As they this night that borén be.

CAVELEIRO

Well give me then a cup of wine,

As thou art his, would thou wert mine.

AVISA

Have t’ye good-luck, tell them that gave

You this advice, what speed you have.

Farewell.

The third trial; wherein are expressed the long passionate, and constant affections

of the close and wary suitor, which by signs, by sighs, by letters, by

privy messengers, by Jewels, Rings, Gold, divers gifts, and by

a long continued course of courtesy at length pre-

vaileth with many both maids and wives if they

be not guarded wonderfully with a better spirit

than their own, which all are here

finely daunted, and mildly over-

thrown by thy constant

answers and chaste

replies of Avisa.[87]

CANT. XXIII.

D. B. A Frenchman [88]

As flaming flakes, too closely pent,

With smothering smoke, in narrow vault,

Each hole doth try to get a vent,

And force by forces fierce assault:

With rattling rage doth rumbling rave,

Till flame and smoke free passage have,

So I (my dear) have smothered long

Within my heart a sparkling flame,

Whose rebel rage is grown so strong

That hope is past to quell the same:

Except the stone that strake [struck] the fire,

With water quench this hot desire[89].

The glancing spear that made the wound,

Which rankling thus hath bred my pain,

Must piercing slide with fresh rebound,

And wound with wound recur again:

That flooring eye that pierced my heart,

Must yield to salve my cureless smart.

I striv’d, but striv'd against the stream

To daunt the qualms of fond desire;

The more their course I did restrain,

More strong and strong they did retire:

Bare need doth force me now to run,

To seek my help, where hurt begun.

Thy present state wants present aid,

A quick redress my grief requires,

Let not the means be long delayed,

That yields us both our heart’s desires:

If you will ease my pensive heart,

I’ll find a salve to heal your smart.

I am no common gambling mate

That lift to bowl in every plain,

But (wench) consider both our state,

The time is now, for both to gain:

From dangerous bands I set you free

If you will yield to comfort me[90].

CANT. XXIIII.

AVISA.

Your fiery flame, your secret smart

That inward frets with pining grief,

Your hollow sighs, your heavy heart,

Methinks might quickly find relief: [91]

If once the certain cause were known,

From whence these hard effects have grown.

It little boots to show your sore

To her that wants all Physic skill,

But tell it them that have in store

Such oils as creeping cankers kill;

I would be glad, to do my best,

If I had skill, to give you rest.

Take heed, let not your grief remain,

Till helps do fail, and hope be past,

For such as first refus’d some pain,

A double pain have felt at last:

A little spark, not quenched by time,

To hideous flames will quickly climb.

If godly sorrow for your sin

Be chiefest cause, why you lament,

If guilty conscience do begin

To draw you truly to repent:

A joyful end must needs redound

To happy grief so seldom found.

To strive all wicked lusts to quell,

Which often sort to doleful end,

I joy to hear you mean so well,

And what you want, the Lord will send:

But if you yield to wanton will,

God will depart, and leave you still.

Your pleasant aid with sweet supply

My present state that might amend,

If honest love be meant thereby,

I shall be glad of such a friend:

But if you love, as I suspect,

Your love and you, I both reject.

CANT. XXV.

D. B. A Frenchman.

What you suspect, I can not tell,

What I do mean, you may perceive;

My works shall show, I wish you well,

If well meant love you list receive:

I have been long in secret mind,

And would be still your secret friend[92].

My love should breed you no disgrace,

None should perceive our secret play,

We would observe both time and place,

That none our dealings should bewray:

Be it my fortune, or my fault,

Love makes me venture this assault.

You mistress of my doubtful chance,

You Prince or this my soul’s desire,

That lulls my fancy in a trance[93],

The mark whereto my hopes aspire;

You see the sore, whence springs my grief,

You wield the stern of my relief.

The gravest men of former time,

That liv'd with fame, and happy life,

Have thought it none, or petty crime,

To love a friend besides their wife:

Then sith my wife you can not be,

As dearest friend account of me.

You talk of sin, and who doth live,

Whose daily steps slide not awry ?

But too precise doth deadly grief

The heart that yields not yet to die:

When age draws on, and youth is past,

Then let us think of this at last.

The Lord did love King David well,

Although he had more wives than one;

King Solomon that did excel,

For wealth and wit, yet he alone

A thousand wives and friends possest,

Yet did he thrive, yet was he blest.

CANT. XXVI.

AVISA.

O mighty Lord that guides the Sphere;

Defend me by thy mighty will

From just reproach, from shame and fear,

Of such as seek my soul to spill:

Let not their counsel (Lord) prevail

To force my heart to yield or quail.

How frames it with your sober looks

To shroud such bent of lewd conceits,

What hope hath plac'd me in your books,

That files me fit for such deceits ?

I hope that time hath made you see

No cause that breeds these thoughts in me.

Your fervent love is filthy lust,

And therefore leave to talk of love,

Your truth is treason under trust,

A Kite in shape of hurtless Dove:

You offer more than friendship would,

To give us brass instead of gold.[94]

Such secret friends to open foes

Do often change with every wind,

Such wandring fits, where folly grows,

Are certain signs of wavering mind:

A fawning face, and faithless heart

In secret love breeds open smart.

No sin to break the wedlock faith?

No sin to swim in Sodom’s sink?

O sin the seed and sting of death!

O sinful wretch that so doth think!

Your gravest men with all their schools,

That taught you thus, were heathen fools.

Your lewd examples will not serve

To frame a virtue from a vice,

When David and his Son did swerve

From lawful rule, though both were wise:

Yet both were plagu’d, as you may see,

With mighty plagues of each degree.

CANT. XXVII.

D. B. A Frenchman.

From whence proceeds this sudden change?

From whence this quaint and coy speech?

Where did you learn to look so strange?

What Doctor taught you thus to preach?

Into my heart it cannot sink

That you do speak as you do think.

Your smiling face and glancing eye

(That promise grace, and not despite)

With these your words do not agree

That seem to shun your chief delight:

But give me leave, I think it still,

Your words do wander from your will.

Of women now the greatest part,

Whose place and age do so require,

Do choose a friend whose faithful heart

May quench the flame of secret fire:

Now if your liking be not plac'd,

I know you will choose one at last.

Then choosing one, let me be he,

If so our hidden fancies frame,

Because you are the only she,

That first inrag’d my fancy’s flame.

If first you grant me this good will,

My heart is yours, and shall be still.

I have a Farm that fell of late

Worth forty pounds at yearly rent;

That will I give to mend your state,

And prove my love is truly meant.

Let not my suit be flat denied,

And what you want shall be supplied.

Our long acquaintance makes me bold

To show my grief, to ease my mind,

For new found friends change not the old,

The like perhaps you shall not find:

Be not too rash, take good advice;

Your hap is good, if you be wise.

CANT. XXVIII.

AVISA

My hap is hard, and over bad

To be misdeem’d of every man;

That think me quickly to be had;

That see me pleasant now and than:

Yet would I not be much aggriev’d

If you alone were thus deceiv’d.

But you alone are not deceiv’d

With tising baits of pleasant view,

But many others have believ’d,

And tried the same as well as you:

But they repent their folly past,

And so will you, I hope at last.

You seem as though you lately came

From London from some bawdy sell [seat, saddle],

Where you have met some wanton dame

That knows the tricks of whores so well. [95]

Know you some wives use more than one?

Go back to them, for here are none.

For here are none that list to choose

A novel chance where old remain,

My choice is past, and I refuse,

While this doth last, to choose again.

While one doth live, I will no more,

Although I beg from door to door.

Bestow your farms among your friends,

Your forty pounds can not provoke

The settled heart, whom virtue binds,

To trust the trains of hidden hook:

The labour’s lost that you endure[96]

To gorged Hawk, to cast the lure.

If lust had led me to the spoil,

And wicked will, to wanton change,

Your betters that have had the foil [repulse, disgrace][97],

Had caus’d me long ere this to range:

But they have left, for they did see,

How far they were mistake of me.

CANT. XXIX.

D. B. A Frenchman.

Mistake indeed if this be true,

If youth can yield to favour’s foe;

If wisdom spring where fancy grew;

But sure I think it is not so:

Let faithful meaning purchase trust

That likes for love, and not for lust.

Although you swear, you will not yield,

Although my death you should intend,

Yet will I not forsake the field,

But still remain your constant friend:

Say what you list, fly where you will,

I am your thrall, to save or spill.

You may command me out of sight

As one that shall no favour find,

But though my body take his flight,

Yet shall my heart remain behind:

That shall your guilty conscience tell,

You have not us'd his master well.

His master’s love he shall repeat,

And watch his turn to purchase grace[98],

His secret eye shall lie in wait;

Where any other gain the place:

When we each others cannot see,

My heart shall make you think of me.

To force a fancy, where is none,

T'is but in vain, it will not bold,

But where it grows itself alone,

A little favour makes it bold:

Till fancy frame your free consent,

I must perforce be needs content.

Though I depart with heavy cheer

As having lost, or left my heart

With one whose love I held too dear,

That now can smile when others smart:

Yet let your prisoner mercy see,

Least you in time a prisoner be.

CANT. XXX.

AVISA.

It makes me smile to see the bent [aim]

Of wandring minds with folly fed,

How fine they feign, how fair they paint

To bring a loving soul to bed[99];

They will be dead [vain], except they have,

What so (forsooth) their fancy crave.

If you did seek, as you pretend,

Not friendless lust, but friendly love,

Your tongue and speeches would not lend

Such lawless actions so to move:

But you can wake, although you wink,

And swear the thing, you never think.

To wavering men that speak so fair,

Let women never credit give[100],

Although they weep, although they swear,

Such feigned shows, let none believe;

For they that think their words be true,

Shall soon their hasty credit rue.[101]

When venturing lust doth make them dare

The simple wenches to betray,

For present time they take no care,

What they do swear nor what they say:

But having once obtain’d the lot,

Their words and oath’s are all forgot.

Let roving Prince [Aeneas] from Troye’s sack,

Whose fawning fram'd Queen Dido's fall,

Teach women wit that wisdom lack;

Mistrust the most, beware of all:

When self-will rules where reason sate [sat],

Fond women oft repent too late.

The wand’ring passions of the mind;

Where constant virtue bares no sway,

Such frantic fickle changes find,

That reason knows not where to stay[102]:

How boast you then of constant love,

Where lust all virtue doth remove?

D. B. Being somewhat grieved with this answer,

after long absence and silence, at length

writeth, as followeth.

CANT. XXXI.

D. B. To A V I S A more pity.

There is a coal that burns the more,

The more ye cast cold water near[103].

Like humour feeds my secret sore,

Not quenched, but fed by cold despair:

The more I feel that you disdain,

The faster doth my love remain.

In Greece they find a burning soil

That fumes in nature like the same[104]:

Cold water makes the hotter broil,

The greater frost, the greater flame.

So frames it with my love or lost

That fiercely fries amidst the frost.

My heart, inflam’d with quenchless heat,

Doth fretting fume in secret fire,

These hellish torments are the meat

That daily feed this vain desire: [105]

Thus shall I groan in ghastly grief,

Till you by mercy send relief.

You first inflam’d my brimstone thought,

Your feigning favour witched mine eye,

O luckless eye that thus hast brought

Thy master’s heart to strive awry:

Now blame yourself if I offend,

The hurt you made, you must amend.

With these my lines I sent a Ring[106],

Least you might think you were forgot,

The posy means a pretty thing,

That bids you Do but dally not.

Do so sweet heart, and do not stay,

For dangers grow from fond delay.

Five winters’ Frosts have said to quell

These flaming fits of firm desire,

Five Summers’ suns cannot expel

The cold despair that feeds the fire[107]:

This time I hope my truth doth try,

Now yield in time, or else I die.

Dudum beatus [formerly happy],

D. B.

CANT. XXXII.

AVISA. To D. B. more wisdom and fear of God.

The Indian men have found a plant

Whose virtue mad conceits doth quell[108],

This root (methinks) you greatly want,

This raging madness to repel:

If rebel fancy work this spite,

Request of God a better sprite.

If you by folly did offend,

By giving reins unto your lust

Let wisdom now these fancies end,

Sith thus untwined is all your trust:

If wit to will will needs resign,

Why should your fault be counted mine?

Your Ring and letter that you sent,

I both return from whence they came,

As one that knows not what is meant

To send or write to me the same:

You had your answer long before,

So that you need to send no more.

Your chosen posy seems to show