- To The Reader

- 1. Shakspere or Shakespeare?

- 2. Shakespeare a Pseudonym?

- 3. Treasure Texts

- 4. Edward de Vere

- 5. Works

- 6. Ben Jonsonís Forgery

- 7. Research for Shake-speare

- 9. Relationship

- 10. Chronology

3.3.2. The Jewe - The Merchant of Venice, 1579

1. Stephen Gosson, The Schoole of Abuse, 1579

In a book with the rather singular title The School of Abuse, registered in July 1579 and published in the same year, the Anglican author Stephen Gosson (1554-1624) declared a most bitter, no-holds-barred war against the world of popular entertainment, his book also bore the subtitle: “a pleasant invective against Poets, Pipers, Players, Jesters and such like Caterpillars of a Commonwealth; setting up the hag of defiance to their mischievous exercise, overthrowing their bulwarks by profane writers, natural reason, and common experience.”

Just a few years previously, Gosson had written plays himself yet in his book he polemicizes against bad theatre, giving credit to the works which distinguish themselves from the run of the mill commercial entertainment. Gosson considered The Jewe to be such a play when it opened in the Bull theatre in Bishop’s Gate. (Bull’s Inn instigated a playhouse which went by the name of “The Theatre” under the auspices of James Burbage.) The Bull may have been used for rehearsals in preparation for a presentation at court or perhaps the theatre troupe moved the production to the Bull after their performance at court.

Gosson’s words make us pay attention. He describes The Jewe as “representing the greediness of worldly choosers and bloody minds of usurers.”

Now often hath her Majesty with the grave advise of her honourable Counsel set down the limits of apparel to every degree, and how soon again hath the pride of our hearts overflown the channel? How many times hath access to Theatres been restrained, and how boldly again have we re-entered? Over lashing in apparel is so common a fault, that the very hirelings of some of our Players, which stand at reversion of vi. s by the week, jet under Gentlemen’s noses in suits of silk, exercising themselves to prating on the stage, and common scoffing when they come abroad, where they look askance over the shoulder at every man, of whom the Sunday before they begged an alms. I speak not this, as though everyone that professeth the quality so abused himself, for it is well known, that some of them are sober, discreet, properly learned honest householders and Citizens well thought on among their neighbours at home, though the pride of their shadows (I mean those hang-byes whom they succour with stipend) cause them to be somewhat ill talked of abroad. And as some of the Players are far from abuse: so some of their Plays are without rebuke: which are as easily remembered as quickly reckoned. The two prose Books played at the Bel Savage[1], where you shall find never a word without wit, never a line without pith, never a letter placed in vain. The Jewe and Ptolome [2], shown at the Bull [3], the one representing the greediness of worldly choosers, and bloody minds of Usurers: the other very lively describing how seditious estates, with their own devises, false friends, with their own swords, and rebellious commons in their own snares are overthrown: neither with amorous gesture wounding the eye: nor with slovenly talk hurting the ears of the chaste hearers. The Black-Smith’s daughter[4], and Catilinʼs Conspiracies[5] usually brought in to the Theatre: the first containing the treachery of Turks, the honorable bounty of a noble mind, and the shining of virtue in distress: the last, because it is known to be a Pig of mine own Sow, I will speak the less of it; only giving you to understand, that the whole mark which I shot at in that work, was to show the reward of traitors in Catilin, and the necessary government of learned men in the person of Cicero, which foresees every danger that is likely to happen, and forestalls it continually ere it take effect. Therefore I give these Plays the commendation, that Maximus Tyrius [6] gave to Homer’s works: “The poetry of Homer is beautiful, the most beautiful, the most brilliant poetry of its genre, the most harmonious, and worthy to be sung by the Muses themselves.” (Dissertations, iii.)

These Plays are good plays and sweet plays, and of all plays the best plays and most to be liked, worthy to be sung of the Muses, or set out with the cunning of Roscius himself, yet are they not fit for every manʼs diet: neither ought they commonly to be shown.[7] Now if any man ask me why myself have penned Comedies in time paste[8], and inveigh so eagerly against them here, let him know that Semel insanivimus omnes [We have all been mad at one time. -Mantuan, Eclogues, I. 118.]: I have sinned, and am sorry for my fault. He runs far that never turns, better late then never. I gave myself to that exercise in hope to thrive but I burnt one candle to seek another, and lost both my time and my travel, when I had done.

To the Gentlewomen Citizens of London, Flourishing days with regard of Credit.

If your grief be such, that you may not disclose it, and your sorrow so great, that you loath to utter it, look for no salve at Plays or theatres, lest that labouring to shun Scylla you light on Charybdis;[9] to for sake the deep you perish in sands; to ward a light stripe, you take a death’s wound; and to leave Physic, you flee to enchanting. You need not go abroad to be tempted, you shall be enticed at your own windows.[10] The best counsel that I can give you, is to keep home, and shun all occasion of ill speech.

2. Gabriel Harvey, Letter-Book, 1579 [11]

The spiritually enlightened puritan Stephen Gosson, was not the only person to see the play The Jewe in 1578-79 and take a strong liking to it (his quote from Maximus Tyrius virtually amounts to a declaration of love); also Gabriel Harvey (1550-1630), the affected-sharp tongued rhetorician who seemed to be lurking in the shadows throughout Oxford’s entire life, mentioned this play. The somewhat presumptuous academic dreamed of completing a work in cooperation with his old school friend Edmund Spencer who had just embarked on a literary career.

The impact of such a work on their contemporaries (Harvey was already planning his next work Three proper and wittie familiar Letters) would be so immense that Spenser should send him by the next carrier ‘the clippings of your thrice honourable mustachios and subboscos[12] to overshadow and to cover my blushing.’ He therefore draws up an obligation or humorous bond between Spenser and himself, by which he agrees to repay his friend one hundred and two hairs of his beard by fixed instalments.”

“Whether these letters ever really passed between the friends," says Edward John Long Scott, the publisher of Harvey’s Letter-Book (1884), "or whether they are the mere creatures of Harvey's imagination, it is now quite impossible to decide”.

Two pleasant and merry conceited letters, one to myself immediately before his Masters Commencement, the other to an odd fantastical Miller that made love to a certain maid of his acquaintance; which two letters I found now perchance amongst a number of mine old scattered papers, and in some considerations thought it not greatly amiss (notwithstanding the levity of the argument in both) to crowd them in for company sake amongst the rest; presuming, as in the rest, of the Author’s pardon, if any trespass be committed herein, or matter of just offence anyway ministered.

The letter to myself verbatim, as it was delivered unto me in an Inn of Court in his own hand.

I shall be content after a new fashion to lend you the choice of as many words and lovely terms as we in England use to deliver our thanks in. Choose whether you will have them given or yielded, rendered or recounted, imparted or repaid, cut out of the whole cloth, or otherwise powered out in the bravest most gallant phrases that are either now already taken up or shall hereafter be devised amongst the finest discoursing tongues. A recital not so fantastical in show as plain and simple in deed. The very payment of a bankrupt; and the only token you are like to receive from me at this present besides a farewell or two of the largest size. A mystical and thrice happy word, wherein is couched the mightiest and sovereingst name (El, the name of God) under and above the heavens. One of the highest and divinest points, that I learned out of Agrippa’s super notable fourth book de Occulta Philosophia. And say now, I have once in my life bestowed upon thee a by-note for thy learning; and so once again take El with thee. - He that is fast bound unto thee in more obligations than any merchant in Italy to any Jew there.

3. Stephen Batman, c. 1580

The fact that we can identify the piece which was so enthusiastically praised by Stephen Gosson as being The Merchant of Venice, or as Gosson called it in 1579; The Jewe must be accredited to Ramon Jimenéz[13], who pointed out that there is a passage in Geoffrey Bullough’s Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare, Vol. I, which clearly states that this is the case. Bullough quotes from Elizabeth J. Brockhurst’s Dissertation of 1947 14 , wherein Brockhurst quotes directly from the hand written notes made by the Anglican preacher, translator and academic Stephen Batman (c.1542-1584) on the subject of the play The Jewe. (In the year 1575 Batman wrote a book with the title Joyfull Newes out of Helvetia, from Theophr. Paracelsum, declaring the ruinate fall of the papal dignitie: also a treatise against Usury.)

The note of a Jew which for the interest of his money required a libra [pound] of the man’s flesh to whom he lent the money, the bond forfeit and yet the Jewe went without his purpose; the party notwithstanding condemned by Law; the question whether he could cut the flesh without spilling of blood. [14]

If we summarise the words of Gosson, Harvey and Batman on the subject of The Jewe then we are left with eight basic characteristics from The Merchant of Venice.

|

Gosson 1579 |

Harvey 1579 |

Batman 1579-84

|

The Merchant of Venice |

|

|

merchant in Italy |

|

a Venetian merchant |

|

greediness of worldly choosers |

|

|

the choice of the three caskets |

|

The Jewe |

a Jew in Italy |

a Jew which for the interest of his money |

the Jew as money lender |

|

bloody minds of usurers |

bound unto |

his money required, the bond forfeit |

bloody forfeit if the repayment day is not met |

|

|

|

a li of the man’s flesh |

the demand of a pound of flesh |

|

|

|

the question whether he could cut the flesh without spilling of blood. |

verdict- a pound of flesh may be removed but no blood may be spilled |

|

|

|

the party notwithstanding condemn’d by Law |

the verdict is fair and just |

|

|

|

the Jewe went without his purpose |

the Jew leaves the court room empty handed |

In other words: either Shake-speare plagiarized The Jewe scene for scene, which we know to be impossible in the light of his other works, or he wrote The Jewe himself. (And isn't it highly unlikely for a play to be staged and then to disappear only to reappear with a different author – SHAKESPEARE - claiming to have written it; without a murmur of protest being voiced by the original author?)

That being the case, it is no longer surprising that Gosson, who is not known for generous acclamations, praises the work quoting the words of Maximus Tyrius: “The poetry … is beautiful, the most beautiful, the most brilliant poetry of its genre, the most harmonious, and worthy to be sung by the Muses themselves.”

4. William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

What are the intrinsic clues in The Merchant of Venice which show that it was written at around 1578-79?

In The man who invented Shakespeare (2009) and Anonymous Shake-speare. The Man Behind (2011) I have demonstrated that Shake-speare’s casket game is full of references to contemporary personages. In view of the fact that my arguments were so shamefully ignored, I see myself force to repeat them.

The rich heiress, Portia of Belmont, the shining light of the story, a true heroine, has a row of foreign aristocratic suitors, each waiting to make a choice, between a golden, a silver and a leaden casket, that will decide if he is to marry Portia or immediately leave Belmont and vow never to marry. Among the premature departures we find the “Neapolitan prince”, the “County Palatine”, “Monsieur Le Bon”, Baron “Falconbridge” and “the Duke of Saxony’s nephew”.

These men are by no means fantasies of the author.

NERISSA. First, there is the Neapolitan prince.

PORTIA. Ay, that’s a colt indeed, for he doth nothing but talk of his horse; and he makes it a great appropriation to his own good parts that he can shoe him himself; I am much afear’d my lady his mother play’d false with a smith. (I/2)

According to H. H. Holland (1933) the “Neapolitan prince” bears a lot of similarity to Prince Don Juan d’Austria (1547–1578). Being the admiral of the Mediterranean fleet, John of Austria often had cause to stay in Naples.

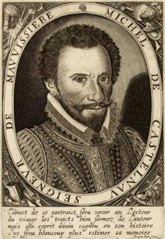

Don Juan d’Austria (John of Austria)

Don Juan’s mother, Barbara Blomberg, the daughter of a harness maker from Regensburg, had an affair with Emperor Charles V. The Emperor is transformed to the “smith”, an irreverent reference to the God Vulcan and his relationship with Venus. The riding skills of the illegitimate Prince are convincingly described by John Lothrop Motley in The Rise of the Dutch Republic (1856): “Throughout the land, there was no man who could match him, be it in piercing the rings or jousting at the tilt. He was famous for his bravery and for his skill in taming the most skittish horse.” In 1575 the Venetian envoy to Naples described Don Juan as being a “well-dressed, fine figure of a man” whose skill with horses was unsurpassed.

Could it be that the whole point of this aristocratic, though rather ignominious cameo appearance was to take a jibe at Queen Elizabeth’s arch enemy Don Juan d’Austria?

If we look a little closer at the virtuous Portia, heiress of Belmont, she proves to be an ideal mirror image of the Virgin Queen. Portia is portrayed as being flawless, mild mannered, knowledgeable, pleasant and well educated. Her wealth is immense; her understanding of the law is superior to that of men. In speech and in bearing she has a regal manner. However, after Bassanio chooses the right casket she surprises him with her subservience:

PORTIA ... But

now I was the lord

Of this fair mansion, master of my servants,

Queen o’er myself: and even now, but now,

This house, these servants and this same myself

Are yours, my lord: I give them with this ring.

Portia’s words throw Bassanio into the sweetest confusion.

BASSANIO. Madam,

you have bereft me of all words;

Only my blood speaks to you in my veins;

And there is such confusion in my powers

As, after some oration fairly spoke

By a beloved prince, there doth appear

Among the buzzing pleased multitude ...

Our laughable parade of suitors continues:

NERISSA. Then is there the County Palatine.

PORTIA. He doth nothing but frown, as who should say ‘An you will not have me,

choose.’ He hears merry tales and smiles not. I fear he will prove the weeping

philosopher when he grows old, being so full of unmannerly sadness in his

youth. I had rather be married to a death’s-head with a bone in his mouth than

to either of these. God defend me from these two!

Louis VI, Elector Palatine of the Rhine (1539–1583) began his rule in 1576. Although his father and his younger brother Johann were Calvinists, Ludwig was a Lutheran.

Louis VI, Elector Palatine

Right at the beginning of his rule, Ludwig forbade the Calvinist services in the Heidelberg palace chapel and rid his household of Calvinists. A sickly person from childhood, he introduced a police state that controlled the citizens according to strict Lutheran rules. He fought vehemently against hedonistic pleasures wherever he could. He even abolished Shrove Tuesday and Saint John the Baptist’s day, holidays that were very popular throughout the land. When he died in 1583 his fun-loving brother (‘The Huntsman from the Electoral Palatinate’) took over the affairs of state.

Nerissa’s next question requires very close attention:

NERISSA. How say

you by the French lord, Monsieur Le Bon?

PORTIA. God made him, and therefore let him pass for a man. In truth, I know it

is a sin to be a mocker, but he – why, he hath a horse better than the

Neapolitan’s, a better bad habit of frowning than the Count Palatine; he is

every man in no man. If a throstle sing he falls straight a-cap’ring; he will

fence with his own shadow; if I should marry him, I should marry twenty husbands.

If he would despise me, I would forgive him; for if he love me to madness, I

shall never requite him.

In the period of time between 1574 and 1584 “Monsieur” was the official term used, when speaking of one of Queen Elizabeth’s most prominent suitors, Hercule-François Duc d’Alençon (1555–1584), the younger brother of the King of France. (The epithet “le Bon” was often seen, as an embellishment to the names of rulers-one is reminded of Jean le Bon, King of France, or Philippe le Bon, Duke of Burgundy.)

Hercule-François Duc d’Alençon

Alençon was a highly strung, fickle and unreliable person, explaining Portia’s remark: “he will fence with his own shadow”. If we feel that the foregoing is insufficient evidence for the conclusion, Alençon = Le Bon perhaps we should ask why he jumps in the air (“he falls straight a capering”), when a “throstle” sings.

The key to the riddle is that “mauvis” is French for “thrush” [old English throstle] and that a certain Michel de Castelnau, Sieur de la Mauvissière (1517–1592) was the French ambassador to the English court. From this position, he championed the cause of the “French marriage” with such fervour and resilience that whenever Mauvissière, the thrush, sang, “Monsieur” began to dance.[15]

The next in line are: Falconbridge, a young Baron from England and his neighbour, a Scot. Falconbridge’s ignorance of Latin, French and modern Italian make it impossible for Portia to even consider him as a suitor. He’s a fine figure of a man, but without the necessary linguistic abilities he remains a figure, and thereby dumb. Shakespeare’s portrayal of the young nobleman avoids any direct reference. The Scot who “borrowed a box of the ear of the Englishman” also remains faceless. Our peripatetic joke once again sets course for Germany.

NERISSA. How like

you the young German, the Duke of Saxony’s nephew?

PORTIA. Very vilely in the morning when he is sober; and most vilely in the

afternoon when he is drunk... Therefore, for fear of the worst, I pray thee set

a deep glass of Rhenish wine on the contrary casket; for if the devil be within

and that temptation without, I know he will choose it.

We may identify “the Duke of Saxony’s nephew” with John Casimir – Count Palatine of Pfalz-Simmern, son in law of Augustus I, Elector of Saxony, and brother in law of Duke Johann Frederick II of Saxony.

John Casimir, Count Palatine

This presumption evolves to certitude when we consider that John Casimir (1543–1592) had also asked for Elizabeth’s hand in marriage. – Blinded by his own high opinion of himself, the young Palatine commissioned Sir James Melville to take portraits of himself and his parents to Queen Elizabeth in the spring of 1564. She received Melville in Hampton Court, where he gave her the two portraits. On the following day Elizabeth gave the portraits back to Melville conveying her gratitude for the pictures, but nonetheless, declining to keep them. “She would have none of them,” Melville said, and wrote to the duke and his father dissuading them “to meddle any more in that marriage.” (Memoirs of Sir James Melville of Halhill [1603], ed. A.F. Steuart, London 1929).

Casimir enjoyed his wine. After he assumed the rule of the Palatinate (following the death of his brother, Louis VI), one of the first things that he did was to have make the biggest wine barrel in the world. The palatine high society drank the entire contents of the barrel (127.000 litres) in two months flat. When he visited London in February 1579 (to seek the Queen's financial support for his campaigns on behalf of the United Provinces), Elizabeth held a two day tournament in his honour. He showed his gratitude with dispatches of wine to Sir Walsingham and Lord Leicester. [16]

Although we know that they don’t have the shadow of a hope, two more sorry candidates must hazard a hopeless guess. The first is the black prince of Morocco; he comes across as a “Miles gloriosus”, a braggart who boasts that no lesser personages than the Shah of Persia and the Sultan of Turkey perished under his mighty sword. The Prince of Morocco could have been one of many black emirs were it not for the fact that the contents of the golden casket, which he chose so proudly and greedily, prophesied the fate of one man and one man alone. Therein lies a death’s-head. Two Maghrebian princes (one ebony and the other nut-brown, in complexion) met their deaths in the fatal battle of Alcazar of 1578 (Alcazar, or Alcazarquivir, lies between Fez and Tangier). The darker of the two victims was a certain Prince Mulay Mohammed otherwise known as Abu Abdallah Mohammed II, who, in alliance with Don Juan d’Austria, ruled over Morocco for a short time.

Mulay Mohammed fought and died – on 4 August 1578 - at the side of the young “Crusader-King” Sebastian of Portugal (1554–1578) who marched on Morocco with an army of 18,000. The majority of Portugal’s aristocracy were among the 8,000 casualties. Two years later Portugal lost her independence and was taken over by Spain. (George Peele in his play The Battle of Alcazar praises the Negro “Muly Mahamet” with the words: “this brave Barbarian Lord Muly Molocco”.)

The casket that springs open to finish our sorry line-up shows the last aspirant a jester’s head-a mirror. The mirror gazer, “Prince of Arragon” by name, had chosen the silver casket, that very metal that his ships speed to him from the new continent. The man behind the name “Arragon” was actually the first suitor whom Elizabeth sent packing, in no uncertain terms. No lesser person than: Philip II, King of Spain (philippvs·rex·aragonvm).

Shakespeare hated the man’s guts and he made no secret of the matter.

King Philip II of Spain

The identification of these six men must lead to a re-appraisal of Shakespearian philology.

First of all the casket game scene is obviously a play on Elizabeth’s “French Wedding” (A sixteenth century version of “Waiting for Godot”) which received enthusiastic acclaim both from critics and theatre goers in the whole of Europe. The main work on the preparation of the marriage contract took place in the time between 1578 and 1583 after which, Elizabeth bought herself out of her promise.

Secondly, the noblemen, parodied here, can be allocated to a specific period in time. Don Juan d’Austria and Prince Mulay Mohammed both died in 1578. The melancholy Elector Palatine departed for a better world in 1583. One year later the bustling Hercule-François Duc d’Alençon followed him to the grave. If the author had waited until the late eighties, or the early nineties of the sixteenth century, his parodies would have been out of date on the opening night. I can say with certitude that the comedy was written in the late seventies of the sixteenth century.

Queen Elizabeth, portrait by Quentin Metsys

Thirdly, the historical references must have been addressed to the Queen’s courtiers and a small circle of aristocrats. The parodies in the play would have been gone over the heads of the audiences in the Swan and the Globe, just as they went over the heads of following generations.

Fourthly, in The Merchant of Venice (III/2) there is a reference to a poem written by Oxford at some time between 1570 and 1580.[17]

Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart or in the head?

How begot, how nourished?

Reply, reply.

It is engend'red in the eyes,

With gazing fed, and fancy dies

In the cradle where it lies.

Let us all ring fancy's knell.

I'll begin it. Ding, dong, bell.

Ding, dong, bell.

To quote Stephen Gosson (1579): “These Plays are good plays and sweet plays, and of all plays the best plays and most to be liked, worthy to be sung of the Muses, or set out with the cunning of Roscius himself, yet are they not fit for every manʼs diet: neither ought they commonly to be shown.”

At this point in time (2017) I wish to add a further item of proof to those which I have already proffered. In her book Hidden Allusions (1931) Eva Turner Clark points out an entry in to the Revels Accounts from 1578-79 –

The history of Portio and demorantes shown at Whitehall on Candlemas day at night [February 2, 1580], enacted by the Lord Chamberlainʼs servants, wholly furnished in this office, whereon was employed for scarfʼs garters, head attires for women, and linings for hats: 6 ells of sarsenett. A city, a town [of canvas], and 6 pair of gloves.[18]

“Portio” is obviously not a name, we can therefore safely assume that the name “Portia” is intended. G. M. Sibley implicitly endorses J. de Perott's conjecture that the subject matter could be Lamorat and Porcia from the 1548 French version of Amadis de Grecia, 1542. Eva Turner Clark’s hypothesis that “demorantes” could stand for “the Merchantes” seems also very imaginative to me. - The Latin word “demorantes” means nothing more than “the persons who are retained at a certain place”, or “the hesitant persons”. This term fit Portia’s suitors perfectly. Once they are located in Portia’s residence where three caskets are presented to them they all hesitate before they give their answers.

Finally there is evidence that The Merchant of Venice was written in 1578-79, which cannot be overlooked. Shake-speare had first-hand knowledge of the Italian novel which served as the inspiration for this work of genius (see 3.3.1 Il Pecorone) - as the following comparison demonstrates:

|

|

Il Pecorone

|

The Merchant of Venice |

|

x |

Venice |

Venice |

|

x |

a merchant and his godson |

a merchant and his young friend |

|

|

bedroom scene and sleeping potion |

the choice of the three caskets |

|

x |

the country of Belmonte |

Portia’s house at Belmont |

|

x |

the Jewe as money lender |

the Jewe as money lender |

|

x |

bloody security, a pound of flesh |

bloody security, a pound of flesh |

|

x |

failure to repay the debt on time |

failure to repay the debt on time |

|

x |

demand of one pound of flesh |

demand of one pound of flesh |

|

x |

the wife as a doctor of laws |

the wife as a doctor of laws |

|

x |

a servant announces the doctor of laws |

the servant announces the doctor of laws |

|

|

the doctor of laws appears in court alone

|

the doctor of laws appears in court accompanied by a servant |

|

x |

verdict- the pound of flesh may be removed but no blood may be spilled |

verdict- the pound of flesh may be removed but no blood may be spilled |

There is only one version of the theme of the money lender who demands a pound of flesh, which Shake-speare could have used for The Merchant of Venice and that is Giovanni Fiorentino’s Il Pecorino. There are those who believe that Shake-speare drew his inspiration from Anthony Munday’s Zelauto without seeing Il Pecorino, but to attribute the similarities between The Merchant of Venice and Il Pecorino to coincidence requires a truly vivid imagination. However if we turn the tables, it is highly likely that Munday used The Merchant of Venice as his inspiration for Zelauto, as will be demonstrated in 3.3.4.1.

NOTES:

[1] Bel Savage. The Bel Savage Inn of Ludgate Hill near St Paul's, was used by a variety of companies, but most notably after 1583 by Elizabeth’s own players, the Queen’s Men, with its famed extempore clown Richard Tarlton. It is safe to say that playing had begun at the Bel Savage by 1576.

[2] Ptolome. Cleopatra was “the queen of Ptolemy” (Antony and Cleopatra, I/4). – See also, Documents Relating to the Office of the Revels in the Time of Queen Elizabeth, ed. by Albert Feuillerat, Louvain 1908, p. 350.

A historie of Telomo [= Ptolome?] shewed before her maiestie at Richmond on Shrovesondaie [February 10, 1583] at night Enacted by the Earle of Leicesters servauntes, for which was prepared and Imployed, one Citty, one Battlement of canvas iij.

[3] The Bull of Bishopsgate Street was presenting plays since 1578.

[4] Anon., performed 1576-1579.

[5] A didactic history play by Gosson, written and performed 1578.

[6] Maximus Tyrius. Maximus of Tyre (fl. late 2nd century AD), also known as Cassius Maximus Tyrius, was a Greek rhetorician and philosopher who lived in the time of the Antonines and Commodus, and who belongs to the trend of the Second Sophistic. His writings contain many allusions to the history of Greece, while there is little reference to Rome. Although nominally a Platonist, he is really an Eclectic and one of the precursors of Neoplatonism.

[7] yet are they not fit for every manʼs diet: neither ought they commonly to be shown.

[8] Gosson’s other plays are Captain Mario, a comedy, and Praise at Parting, a morality, both written 1577.

[9] lest that labouring to shun Scylla you light on Charybdis. In The Date of The Merchant of Venice (The Oxfordian, Vol. XIII, 2011) Ramon Jimenéz uncovers two hitherto parallels between Gosson’s The Schoole of Abuse and Shakespeare’s The Merchant which had been hitherto ignored.- See The Merchant of Venice, III/5:

LAUNCELOT. Marry, you may

partly hope that your father got you not- that you are not the Jew's daughter.

JESSICA. That were a kind of bastard hope indeed; so the sins of my mother

should be visited upon me.

LAUNCELOT. Truly then I fear you are damn'd both by father and mother; thus when I shun Scylla, your father, I fall into Charybdis,

your mother; well, you are gone both ways.

[10] You need not go abroad to be tempted, you shall be enticed at your own windows. See The Merchant of Venice, II/5:

SHYLOCK. What, are there masques? Hear you me,

Jessica:

Lock up my doors, and when you hear the

drum,

And the vile squealing of the wry-neck'd

fife,

Clamber not you up to the casements

then,

Nor thrust your head into the public

street

To gaze on Christian fools with

varnish'd faces;

But stop my house's ears- I mean my

casements;

Let not the sound of shallow fopp'ry

enter

My sober house.

[11] Gabriel Harvey, Letter-Book, 1579. Source: Letter-Book from Gabriel Harvey, 1573-1580, ed. by Edward John Long Scott, London 1884, pp. 77-78.

[12] subboscos. the hair that grows upon the lower part of the face

[13] must be accredited to Ramon Jimenéz. See, Ramon Jimenéz, The Date of The Merchant of Venice, The Oxfordian, Vol. XIII, 2011.

[14] The note of a Jew … without spilling of blood. Stephen Batman, being chaplain to Archbishop Matthew Parker, assisted Parker in assembling a large collection of medieval manuscripts to justify the Anglican cause. The annotation in his handwriting reads as follows –

The note of a Jew wch for the interest of his money required a li of the mans flesh to whome he lent the money, the bonde forfeit and yet the Jewe went wthoute his purpose / the parti notwithstanding condemn’d by Lawe / the question whether he coulde cut the flesh wthoute spilling of blood.

[15] whenever Mauvissière, the thrush, sang, “Monsieur” began to dance. Wikipedia: ‘Michel de Castelnau, Sieur de la Mauvissière (c.1520–1592) was one of a large family of children, and his grandfather, Pierre de Castelnau, was Equerry (Master of the Horse) to Louis XII. Endowed with a clear and penetrating intellect and remarkable strength of memory, he received a careful education, capped off with travels in Italy and a long stay at Rome. - In 1572 he was sent to England by Charles IX to allay the excitement created by the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, and the same year he was sent to Germany and Switzerland. Two years later he was reappointed by Henry III ambassador to Queen Elizabeth, and he remained at her court for ten years. During this period he used his influence to promote the marriage of the queen with the Duke of Alençon, with a view especially to strengthen and maintain the alliance of the two countries. But Elizabeth made so many promises only to break them that at last he refused to accept them or communicate them to his government.’ - See also 7.2.5 Oxford and France.

[16] He showed his gratitude with dispatches of wine to Sir Walsingham and Lord Leicester. John Casimir was in regular contact with Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and his nephew Sir Philip Sidney who, as agent for Elizabeth I, was sent to the continent to assist in the formation of a Protestant league. - See 7.2.5 Oxford and France, notes 28 and 30.

[17] Tell me where is fancy bred ... Ding, dong, bell. In Oxford’s poem which is the English adaptation of an Italian ‘Sonetto in dialogo’, the word fancy is used to depict Desire (=Amor).- See 5.2.3 The Poems, No. 91.

When wert thou born, Desire? - In pomp and prime of

May.

By whom, sweet boy, wert thou begot? - By good conceit, men say.

Tell me, who was thy nurse? - Fresh youth in sugared joy.

What was thy meat and daily food? - Sore sighs with great annoy.

What had you then to drink? - Unfeigned lovers' tears.

What cradle were you rocked in? - In hope devoid of fears.

What brought you then asleep? - Sweet speach that liked men best.

And where is now your dwelling place? - In gentle hearts I rest.

Doth company displease? - It doth in many one.

Where would Desire then choose to be? - He likes to muse alone.

What feedeth most your sight? - To gaze on favour still.

Who find you most to be your foe? - Disdain of my good will.

Will ever age or death bring you unto decay? -

No, no, Desire both lives and dies ten thousand times a day.

[18] In original spelling:

The history of Portio and demorantes shewen at Whitehall on Candlemas daie at nighte enacted by the Lord Chamberleyns seruauntes wholly furnyshed in this offyce whereon was ymployed for scarfes garters head Attyers for women & Lynynges for hatts vj ells of Sarcenett A cytie a towne & vj payre of gloves. (Documents Relating to the Office of the Revels in the Time of Queen Elizabeth, ed. by Albert Feuillerat, Louvain 1908, p. 321.)

.