5.1. The Adventures of Master F. I. (1573)

THE ADVENTURES OF MASTER F. I. (1573)

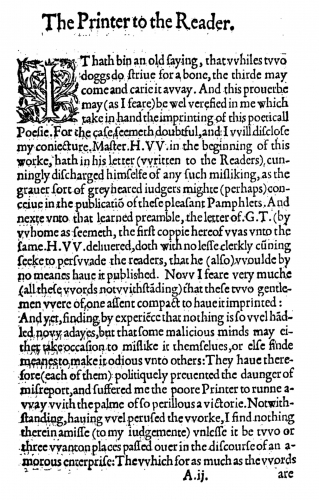

The Printer [A. B.] to the Reader.[1]

It hath been an old saying that while two dogs do strive for a bone the third may come and carry it away. And this proverb may (as I fear) be well verified in me which take in hand the imprinting of this poetical posy. For the case seemeth doubtful, and I will disclose my conjecture:

Master H. W. in the beginning of this work hath in his letter written to the Readers cunningly discharged himself of any such misliking as the graver sort of grayhaired judgers might perhaps conceive in the publication of these pleasant Pamphlets.

And next unto that learned preamble, the letter of G. T. (by whom as seemeth, the first copy hereof was unto the same H. W. delivered) doth with no less clerkly cunning seek to persuade the readers that he also would by no means have it published.

Now I fear very much -- all these words notwithstanding -- that these two gentlemen were of one assent compact to have it imprinted, and yet, finding by experience that nothing is so wellhandled nowadays but that some malicious minds may either take occasion to mislike it themselves or else find means to make it odious unto others, they have therefore each of them politicly prevented the danger of misreport, and suffered me the poor Printer to run away with the palm of so perilous a victory.

Notwithstanding, having well perused the work, I find nothing therein amiss to my judgment, unless it be two or three wanton places passed over in the discourse of an amorous enterprise. The which for as much as the words are cleanly, (although the thing meant be somewhat natural), I have thought good also to let them pass as they came to me, and the rather because (as Master H. W. hath well alleged in his letter to the Reader) the well-minded man may reap some commodity out of the most frivolous works that are written. And as the venomous spider wilt suck poison out of the most wholesome herb, and the industrious Bee can gather honey out of the most stinking weed, even so the discrete reader may take a happy example by the most lascivious histories, although the captious and harebrain'd heads can neither be encouraged by the good nor forewarned by the bad. And thus much I have thought good to say in excuse of some savours which may perchance smell unpleasantly to some noses in some part of this poetical posy.

Now it hath with this fault a greater commodity than common posies have ben accustomed to present, and that is this: you shall not be constrained to smell of the flowers therein contained all at once, neither yet to take them up in such order as they are sorted. But you may take any one flower by itself, and if that smell not so pleasantly as you would wish, I doubt not yet but you may find some other which may supply the defects thereof.

As thus: he which would have good moral lessons clerkly handled, let him smell to the Tragedy translated out of Euripides. He that would laugh at a pretty conceit closely conveyed, let him peruse the comedy translated out of Ariosto. He that would take example by the unlawful affections of a lover bestowed upon an unconstant dame, let them read the report in verse made by Dan Bartholmew of Bath, or the discourse in prose of the adventures passed by master F. I. (whom the reader may name Freeman Iones [2] ), for the better understanding of the same. He that would see any particular pang of love lively displayed, may here approve every Pamphlet by the title, and so remain contented. As also divers godly hymns and Psalms may in like manner be found in this record.

To conclude, the work is so universal as, either in one place or other, any man's mind may therewith be satisfied. The which I adventure (under pretext of this promise) to present unto all indifferent eyes as followeth.

H. W. to the Reader.

In August last passed, my familiar friend Master G. T. bestowed upon me the reading of a written Book wherein he had collected divers discourses & verses invented upon sundry occasions by sundry gentlemen, in mine opinion right commendable for their capacity. And herewithal my said friend charged me that I should use them only for mine own particular commodity, and eftsoons safely deliver the original copy to him again; wherein I must confess myself but half a merchant, for the copy unto him I have safely redelivered.

But the work (for I thought it worthy to be published) I have entreated my friend A.B. to imprint: as one that thought better to please a number by common commodity then to feed the humor of any private person by needless singularity. This I have adventured for thy contentation, learned Reader. And further have presumed of myself to christen it by the name of A hundred sundry Flowers: In which poetical posy are set forth many trifling fantasies, humoral passions, and strange affects of a lover.

And therein (although the wiser sort would turn over the leaf as a thing altogether fruitless) yet I myself have reaped this commodity, to sit and smile at the fond devises of such as have enchained themselves in the golden fetters of fantasy, and having bewrayed themselves to the whole world, do yet conjecture that they walk unseen in a net. Some other things you may also find in this Book which are as void of vanity as the first are lame for government.

And I must confess that (what to laugh at the one, & what to learn by the other) I have contrary to the charge of my said friend G. T. procured for these trifles this day of publication. Whereat if the authors only repine, and the number of other learned minds be thankful, I may then boast to have gained a bushel of good will in exchange for one pint of peevish choler.[3]

But if it fall out contrary to expectation that the readers judgments agree not with mine opinion in their commendations, I may then (unless their courtesies supply my want of discretion), with loss of some labor, accompt also the loss of my familiar friends; in doubt whereof, I cover all our names, and refer you to the well written letter of my friend G. T. next following, whereby you may more at large consider of these occasions.

And so I commend the praise of other mens travails, together with the pardon of mine own rashness, unto the well willing minds of discrete readers. From my lodging near the Strande the 20th of Ianuary, 1572 [= 1573].[4]

The letter of G. T. to his very friend H. W. concerning this work.

Remembering the late conference passed between us in my lodging, and how you seemed to esteem some Pamphlets which I did there show unto you far above their worth in skill, I did straightway conclude the same your judgment to proceed of two especial causes: One (and principal), the stedfast good will which you have ever hitherto sithens our first familiarity borne towards me. Another (of no less weight), the exceeding zeal and favor that you bear to good letters. The which (I agree with you) do no less bloom and appear in pleasant ditties or compendious Sonnets devised by green youthful capacities than they do fruitfully flourish unto perfection in the riper works of grave and grayhaired writers. For as in the last, the younger sort may make a mirror of perfect life, so in the first, the most frosty bearded Philosopher may take just occasion of honest recreation not altogether without wholesome lessons tending to the reformation of manners. For who doubteth but that Poets in their most feigned fables and imaginations have metaphorically set forth unto us the right rewards of virtues and the due punishments for vices?

Marry, indeed, I may not compare Pamphlets unto Poems, neither yet may justly advant for our native countrymen that they have in their verses hitherto (translations excepted) delivered unto us any such notable volume as have been by Poets of antiquity left unto the posterity. And the more pity that amongst so many toward wits no one hath been hitherto encouraged to follow the trace of that worthy and famous Knight Sir Geoffrey Chaucer and, after many pretty devises spent in youth for the obtaining a worthless victory, might consume and consummate his age in describing the right pathway to perfect felicity with the due preservation of the same. The which, although some may judge over grave a subject to be handled in style metrical, yet for that I have found in the verses of eloquent Latinists, learned Greeks, & pleasant Italians, sundry directions whereby a man may be guided toward th'attaining of that unspeakable treasure, I have thus far lamented, that our countrymen have chosen rather to win a passover praise by the wanton penning of a few loving lays than to gain immortal fame by the clerkly handling of so profitable a Theme. For if quickness of invention, proper vocables, apt Epithets, and store of monosyllables may help a pleasant brain to be crowned with Laurel, I doubt not but both our countrymen & country language might be enthronized among the old foreleaders unto the mount Helicon.

But now let me return to my first purpose, for I have wandered somewhat beside the path, and yet not clean out of the way. I have thought good (I say) to present you with this written book, wherein you shall find a number of Sonnets, lays, letters, Ballads, Rondelets, verlays and verses, the works of your friend and mine, Master F. I., and divers others, the which when I had with long travail confusedly gathered together, I thought it then Opere precium to reduce them into some good order. The which I have done, according to my barren skill, in this written Book, commending it unto you to read and to peruse, and desiring you, as I only do adventure thus to participate the sight thereof unto your former good will, even so that you will by no means make the same common: but after your own recreation taken therein that you will safely redeliver unto me the original copy. For otherwise I shall not only provoke all the authors to be offended with me, but further shall lose the opportunity of a greater matter, half and more granted unto me already, by the willing consent of one of them.

And to be plain with you, my friend, he hath written, which as far as I can learn did never yet come to the reading or perusing of any man but himself, two notable works. The one called the Sundry lots of love. The other of his own invention entitled The climbing of an Eagles nest. These things (and especially the later) doth seem by the name to be a work worthy the reading. And the rather I judge so because his fantasy is so occupied in the same, as that contrary to his wonted use, he hath hitherto withheld it from sight of any of his familiars until it be finished, you may guess him by his Nature. And therefore I require your secrecy herein, least if he hear the contrary, we shall not be able by any means to procure these other at his hands.

So fare you well, from my Chamber this tenth of August, 1572.

Yours or not his own.

G. T.

When I had with no small entreaty obtained of Master F. I. and sundry other toward young gentlemen the sundry copies of these sundry matters, then as well for that the number of them was great, as also for that I found none of them so barren but that (in my judgment) had in it aliquid salis[5], and especially being considered by the very proper occasion whereupon it was written (as they themselves did always with the verse rehearse unto me the cause that then moved them to write), I did with more labor gather them into some order, and so placed them in this register. Wherein as near as I could guess, I have set in the first places those which Master F. I. did compile.

And to begin with this his history that ensueth, it was (as he declared unto me) written upon this occasion. The said F. I. chanced once, in the north parts of this Realm, to fall in company of a very fair gentlewoman whose name was Mistress Ellinor, unto whom bearing a hot affection, he first adventured to write this letter following.

|

Mistress, I pray you understand that being altogether a stranger in these parts, my good hap hath been to behold you to my (no small) contentation, and my evil hap accompanies the same with such imperfection of my deserts as that I find always a ready repulse in mine own frowardness. So that considering the natural climate of the country, I must say that I have found fire in frost. And yet comparing the inequality of my deserts with the least part of your worthiness, I feel a continual frost in my most fervent fire. Such is then th'extremity of my passions, the which I could never have been content to commit unto this telltale paper were it not that I am destitute of all other help. Accept therefore, I beseech you, the earnest good will of a more trusty than worthy servant, who, being thereby encouraged, may supply the defects of his ability with ready trial of dutiful loyalty. And let this poor paper (besprent with salt tears, and blowen over with scalding sighs) be saved of you as a safe guard for your sampler, or a bottom to wind your sowing silk, that when your last needlefull is wrought, you may return to reading thereof and consider the care of him who is More yours than his own. |

This letter by her received (as I have heard him say) her answer was this:

She took occasion one day at his request to dance with him, the which doing, she bashfully began to declare unto him that she had read over the writing which he delivered unto her, with like protestation, that, as at delivery thereof, she understood not for what cause he thrust the same into her bosom, so now she could not perceive thereby any part of his meaning, nevertheless at last seemed to take upon her the matter, and though she disabled herself, yet gave him thanks as &c.

Whereupon he brake the brawl, and walking abroad devised immediately these few verses following.

|

[Nr 3] Fair Bersabe the bright once, bathing in a well [6] Fair Bersabe the bright once, bathing in a well, L'envoi. To you these few suffice, your wits be quick and good, F. I. |

I have heard the Author say, that these were the first verses that ever he wrote upon like occasion.[7]The which, considering the matter precedent, may in my judgment be well allowed, and to judge his doings by the effects, he declared unto me that before he could put the same in legible writing, it pleased the said Mistress Ellinor of her courtesy thus to deal with him.

Walking in a garden among divers other gentlemen & gentlewomen, with a little frowning smile in passing by him, she delivered unto him a paper with these words: "For that I understand not," quoth she, "th'intent of your letters, I pray you take them here again, and bestow them at your pleasure." The which done and said, she passed by without change either of pace or countenance.

F. I. somewhat troubled with her angry look, did suddenly leave the company, & walking into a park near adjoining, in great rage began to wreak his malice on this poor paper, and the same did rend and tear in pieces. When suddenly at a glance he perceived it was not of his own handwriting, and therewithal abashed, upon better regard he perceived in one piece thereof written in Roman these letters SHE:, wherefore placing all the pieces thereof as orderly as he could, he found therein written these few lines hereafter following.[8]

|

Your sudden departure from our pastime yesterday did enforce me for lack of chosen company to return unto my work, wherein I did so long continue till at the last the bare bottom did draw unto my remembrance your strange request. And although I found therein no just cause to credit your colored words, yet have I thought good hereby to requite you with like courtesy, so that at least you shall not condemn me for ungrateful. But as to the matter therein contained, if I could persuade myself that there were in me any coals to kindle such sparks of fire, I might yet peradventure be drawn to believe that your mind were frozen with like fear. But as no smoke ariseth where no coal is kindled, so without cause of affection the passion is easy to be cured. This is all that I understand of your dark letters. And as much as I mean to answer. SHE. |

My friend F. I. hath told me divers times that immediately upon receipt hereof, he grew in jealousy that the same was not her own device. And therein I have no less allowed his judgment then commended his invention of the verses and letters before rehearsed. For as by the style this letter of hers bewrayeth that it was not penned by a woman's capacity, so the sequel of her doings may decipher that she had mo' ready clerks then trusty servants in store.

Well, yet as the perfect hound, when he hath chased the hurt deer amid the whole herd, will never give over till he have singled it again, even so F. I., though somewhat abashed with this doubtful show, yet still constant in his former intention, ceased not by all possible means to bring this Deer yet once again to the Bows whereby she might be the more surely stricken, and so in the end enforced to yield. Wherefore he thought not best to commit the said verses willingly into her custody, but privily lost them in her chamber, written in counterfeit. And after on the next day thought better to reply, either upon her or upon her Secretary, in this wise as here followeth.

|

The much that you have answered is very much, and much more than I am able to reply unto. Nevertheless, in mine own defense thus much I allege: that if my sudden departure pleased not you, I cannot myself therewith be pleased, as one that seeketh not to please many and more desirous to please you then any. The cause of mine affection, I suppose you behold daily, for (self love avoided) every wight may judge of themselves as much as reason persuadeth. The which if it be in your good nature suppressed with bashfulness, then mighty Iove grant you may once behold my wan cheeks washed in woe that therein my salt tears may be a mirror to represent your own shadow, and that like unto Narcissus you may be constrained to kiss the cold waves wherein your counterfeit is so lively portrayed. For if abundance of other matters failed to draw my gazing eyes in contemplation of so rare excellency, yet might these your letters both frame in me an admiration of such divine esprit and a confusion to my dull understanding which so rashly presumed to wander in this endless Labyrinth. Such I esteem you, and thereby am become such, and even HE. F. I. |

This letter finished and fair written over, his chance was to meet her alone in a Gallery of the same house: where (as I have heard him declare) his manhood in this kind of combat was first tried, and therein I can compare him to a valiant Prince, who distressed with power of enemies had committed the safeguard of his person to treaty of Ambassade, and suddenly (surprised with a Camisado in his own trenches) was enforced to yield as prisoner. Even so my friend F. I., lately overcome by the beautiful beams of this Dame Ellinor, and having now committed his most secret intent to these late rehearsed letters, was at unawares encountered with his friendly foe, and constrained either to prepare some new defense, or else like a recreant to yield himself as already vanquished.

Wherefore (as in a trance) he lifted up his dazzled eyes, & so continued in a certain kind of admiration, not unlike the Astronomer who (having, after a whole nights travail, in the grey morning found his desired star) hath fixed his hungry eyes to behold the Comet long looked for: whereat this gracious Dame (as one that could discern the sun before her chamber windows were wide open) did deign to embolden the fainting Knight with these or like words.

"I perceive now," quoth she, "how mishap doth follow me, that having chosen this walk for a simple solace, I am here disquieted by the man that meaneth my destruction." & therewithal, as half angry, began to turn her back, when as my friend F. I., now awaked, 'gan thus salute her.

"Mistress," quoth he, "and I perceive now that good hap haunts me, for being by lack of opportunity constrained to commit my welfare unto these blabbing leaves of bewraying paper," (showing that in his hand) "I am here recomforted with happy view of my desired joy." & therewithal, reverently kissing his hand [9], did softly distrain her slender arm & so stayed her departure.

The first blow thus proffered & defended, they walked & talked traversing divers ways, wherein I doubt not but that my friend F. I. could quit himself reasonably well. And though it stood not with duty of a friend that I should therein require to know his secrets, yet of himself he declared thus much, that after long talk she was contented to accept his proffered service, but yet still disabling herself and seeming to marvel what cause had moved him to subject his liberty so willfully, or at least in a prison (as she termed it) so unworthy.

Whereunto I need not rehearse his answer but suppose now that thus they departed: saving I had forgotten this, she required of him the last rehearsed letter, saying that his first was lost & now she lacked a new bottom for her silk, the which I warrant you he granted: and so proffering to take an humble congé by Bezo las manos, she graciously gave him the zuccado dez labros [10]: and so for then departed.

And thereupon recounting her words, he compiled these following, which he termed Terza sequenza, to sweet Mistress SHE.

|

[Nr 4] Of thee dear Dame, three lessons would I learn Of thee dear Dame, three lessons would I learn[11]: And then It is a heaven to see them hop and skip, For when I first beheld that heavenly hue of thine, Till then and ever. HE. F. I. |

When he had well sorted this sequence, he sought oportunity to leave it where she might find it before it were lost.

And now the coals began to kindle whereof but erewhile she feigned herself altogether ignorant. The flames began to break out on every side, & she to quench them shut up herself in her chamber solitarily. But as the smithy gathers greater heat by casting on of water, even so the more she absented herself from company, the fresher was the grief which galded her remembrance: so that at last the report was spread through the house that Mistress Ellinor was sick. At which news F. I. took small comfort: nevertheless Dame Venus with good aspect did yet thus much further his enterprise.

The Dame (whether it were by sudden change, or of wonted custom) fell one day into a great bleeding at the nose. For which accident, the said F. I., amongst other pretty conceits, hath a present remedy, whereby he took occasion (when they of the house had all in vain sought many ways to stop her bleeding) to work his feat in this wise:

First, he pleaded ignorance, as though he knew not her name, and therefore demanded the same of one other Gentlewoman in the house (whose name was Mistress Frances), who when she had to him declared that her name was Ellinor, he said these words or very like in effect: "If I thought I should not offend Mistress Ellinor, I would not doubt to stop her bleeding without either pain or difficulty."

This gentlewoman, somewhat tickled with his words, did incontinent make relation thereof to the said Mistress Ellinor, who immediately (declaring that F. I. was her late received servant) returned the said messenger unto him with especial charge that he should employ his devoir towards the recovery of her health, with whom the same F. I. repaired to the chamber of his desired: and, finding her set in a chair leaning on the one side over a silver basin, after his due reverence, he laid his hand on her temples and, privily rounding her in her ear, desired her to command a Hazel stick and a knife. The which being brought, he delivered unto her, saying on this wise.

"Mistress, I will speak certain words in secret to myself and do require no more but when you hear me say openly this word Amen, that you with this knife will make a nick upon this hazel stick. And when you have made five nicks, command me also to cease."

The Dame, partly of good will to the knight and partly to be stanched of her bleeding, commanded her maid and required the other gentils somewhat to stand aside. Which done, he began his orisons, wherein he had not long muttered before he pronounced Amen, wherewith the Lady made a nick on the stick with her knife. The said F. I. continued to another Amen, when the Lady having made another nick felt her bleeding began to stanch: and so by the third Amen thoroughly stanched.

F. I. then changing his prayers into private talk, said softly unto her, "Mistress, I am glad that I am hereby enabled to do you some service, and as the stanching of your own blood may some way recomfort you, so if the shedding of my blood may any way content you, I beseech you command it, for it shall be evermore readily employed in your service," and therewithal with a loud voice pronounced Amen.

Wherewith the good Lady making a nick did secretly answer thus: "Good servant," quoth she, "I must needs think myself right happy to have gained your service and good will, and be you sure that although there be in me no such desert as may draw you into this depth of affection, yet such as I am, I shall be always glad to show myself thankful unto you, and now, if you think yourself assured that I shall bleed no more, do then pronounce your fifth Amen," the which pronounced, she made also her fifth nick, and held up her head, calling the company unto her and declaring unto them that her bleeding was thoroughly stanched.

Well, it were long to tell what sundry opinions were pronounced upon this act, and I do dwell overlong in the discourses of this F. I., especially having taken in hand only to copy out his verses, but for the circumstance doth better declare the effect, I will return to my former tale.

F. I., tarrying a while in the chamber, found opportunity to lose his sequence near to his desired Mistress: and after congé taken, departed. After whose departure, the Lady arose out of her chair, & her maid, going about to remove the same, espied & took up the writing. The which her mistress perceiving, gan suddenly conjecture that the same had in it some like matter to the verses once before left in like manner, & made semblant to mistrust that the same should be some words of conjuration: and taking it from her maid, did peruse it & immediately said to the company that she would not forgo the same for a great treasure. But to be plain, I think that (F. I. excepted) she was glad to be rid of all company until she had with sufficient leisure turned over & retossed every card in this sequence.

And not long after, being now tickled thorough all the veins with an unknown humor, adventured of herself to commit unto a like Ambassador the deciphering of that which hitherto she had kept more secret, & thereupon wrote with her own hand & head in this wise:

|

Good servant, I am out of all doubt much beholding unto you, and I have great comfort by your means in the stanching of my blood, and I take great comfort to read your letters, and I have found in my chamber divers songs which I think to be of your making, and I promise you, they are excellently made, and I assure you that I will be ready to do for you any pleasure that I can during my life: wherefore I pray you come to my chamber once in a day till I come abroad again, and I will be glad of your company, and for because that you have promised to be my HE: I will take upon me this name, your SHE. |

This letter I have seen of her own handwriting. And as therein the Reader may find great difference of Style from her former letter, so may you now understand the cause. She had in the same house a friend, a servant, a Secretary: what should I name him? such one as she esteemed in time past more than was cause in time present, and to make my tale good, I will (by report of my very good friend F. I.) describe him unto you. He was in height the proportion of two Pigmies, in breadth the thickness of two bacon hogs, of presumption a Giant, of power a Gnat, Apishly witted, Knavishly manner'd, & crabbedly favored. What was there in him then to draw a fair Lady's liking? Marry sir, even all in all, a well lined purse, wherewith he could at every call provide such pretty conceits as pleased her peevish fantasy, and by that means he had thoroughly (long before) insinuated himself with this amorous dame.

This manling, this minion, this slave, this secretary, was now by occasion ridden to London forsooth: and though his absence were unto her a disfurnishing of eloquence, it was yet unto F. I. an opportunity of good advantage, for when he perceived the change of her style, and thereby grew in some suspicion that the same proceeded by absence of her chief Chancellor, he thought good now to smite while the iron was hot and to lend his Mistress such a pen in her Secretaries absence as he should never be able at his return to amend the well writing thereof. Wherefore according to her command he repaired once every day to her chamber at the least, whereas he guided himself so well and could devise such store of sundry pleasures and pastimes that he grew in favor not only with his desired but also with the rest of the gentlewomen.

And one day passing the time amongst them, their play grew to this end, that his Mistress, being Queen, demanded of him these three questions. "Servant," quoth she, "I charge you, as well upon your allegiance being now my subject, as also upon your fidelity having vowed your service unto me, that you answer me these three questions by the very truth of your secret thought. First, what thing in this universal world doth most rejoice and comfort you?"

F. I., abasing his eyes towards the ground, took good advisement in his answer, when a fair gentlewoman of the company clapped him on the shoulder, saying, "How now sir, is your hand on your halfpenny?"

To whom he answered, "No, fair Lady, my hand is on my heart, and yet my heart is not in mine own hands": wherewithal abashed, turning towards dame Ellinor he said, "My sovereign & Mistress, according to the charge of your command and the duty that I owe you, my tongue shall bewray unto you the truth of mine intent. At this present, a reward given me without desert doth so rejoice me with continual remembrance thereof, that though my mind be so occupied to think thereon as that day nor night I can be quiet from that thought, yet the joy and pleasure which I conceive in the same is such that I can neither be cloyed with continuance thereof, nor yet afraid that any mishap can countervail so great a treasure. This is to me such a heaven to dwell in as that I feed by day and repose by night upon the fresh record of this reward." (This, as he sayeth. he meant by the kiss that she lent him in the Gallery, and by the profession of her last letters and words.)

Well, though this answer be somewhat misty, yet let my friend's excuse be that taken upon the sudden he thought better to answer darkly than to be mistrusted openly.

Her second question was, what thing in this life did most grieve his heart and disquiet his mind, whereunto he answered that although his late rehearsed joy were incomparable, yet the greatest enemy that disturbed the same was the privy worm of his own guilty conscience, which accused him evermore with great unworthiness: and that this was his greatest grief.

The Lady, biting upon the bit at his cunning answers made unto these two questions, gan thus reply. "Servant, I had thought to have touched you yet nearer with my third question, but I will refrain to attempt your patience. And now for my third demand, answer me directly: in what manner this passion doth handle you? and how these contraries may hang together by any possibility of concord? For your words are strange."

F. I., now rousing himself boldly, took occasion thus to handle his answer. "Mistress," quoth he, "my words indeed are strange, but yet my passion is much stranger, and thereupon this other day to content mine own fantasy I devised a Sonnet, which although it be a piece of Cockerels music and such as I might be ashamed to publish in this company, yet because my truth in this answer may the better appear unto you, I pray you vouchsafe to receive the same in writing," and drawing a paper out of his packet presented it unto her, wherein was written this Sonnet.

|

[Nr 5] Love, hope, and death do stir in me such strife Love, hope, and death do stir in me such strife, even HE. F. I. |

This Sonnet was highly commended, and in my judgment it deserveth no less. I have heard F. I. say that he borrowed th'invention of an Italian[12]: but, were it a translation or invention, (if I be judge) it is both pretty and pithy.

His duty thus performed, their pastimes ended; and, at their departure, for a watchword he counseled his Mistress by little and little to walk abroad, saying that the Gallery near adjoining was so pleasant, as if he were half dead he thought that by walking therein he might be half and more revived.

"Think you so, servant?" quoth she. "And the last time that I walked there I suppose I took the cause of my malady, but by your advice, and for you have so clerkly stanched my bleeding, I will assay to walk there tomorrow."

"Mistress," quoth he, "and in more full accomplishment of my duty towards you and in sure hope that you will use the same only to your own private commodity, will there await upon you, & between you & me will teach you the full order how to stanch the bleeding of any creature, whereby you shall be as cunning as myself."

"Gramercy, good servant," quoth she, "I think you lost the same in writing here yesterday, but I cannot understand it, and therefore tomorrow (if I feel myself any thing amended) I will send for you thither to instruct me thoroughly." Thus they departed.

And at supper time, the Knight of the Castle, finding fault that his guest's stomach served him no better, began to accuse the grossness of his viands. To whom one of the gentlewomen which had passed the afternoon in his company answered, "Nay sir," quoth she, "this gentleman hath a passion, the which once in a day at the least doth kill his appetite."

"Are you so well acquainted with the disposition of his body?" quoth the Lord of the house.

"By his own saying," quoth she, "& not otherwise."

"Fair Lady," quoth F. I., "you either mistook me or overheard me then, for I told of a comfortable humor which so fed me with continual remembrance of joy as that my stomach being full thereof doth desire in manner none other victuals."

"Why sir," quoth the host, "do you then live by love?"

"God forbid, Sir," quoth F. I., "for then my cheeks would be much thinner then they be, but there are divers other greater causes of joy then the doubtful lots of love, and for mine own part, to be plain, I cannot love and I dare not hate."

"I would I thought so," quoth the gentlewoman.

And thus with pretty nips they passed over their supper: which ended, the Lord of the house required F. I. to dance and pass the time with the gentlewomen, which he refused not to do. But suddenly, before the music was well tuned, came out Dame Ellinor in her night attire and said to the Lord that (supposing the solitariness of her chamber had increased her malady) she came out for her better recreation to see them dance.

"Well done, daughter," quoth the Lord.

"And I, Mistress," quoth F. I., "would gladly bestow the leading of you about this great chamber, to drive away the faintness of your fever."

"No, good servant," quoth the Lady, "but in my stead I pray you dance with this fair Gentlewoman," pointing him to the Lady that had so taken him up at supper. F. I. to avoid mistrust, did agree to her request without further entreaty. The dance begun, this Knight marched on with the Image of St.Frances in his hand, and St. Ellinor in his heart.

The violins at end of the pavan stayed a while, in which time this Dame said to F. I. on this wise: "I am right sorry for you in two respects, although the familiarity have hitherto had no great continuance between us, and as I do lament your case, so do I rejoice (for mine own contentation) that I shall now see a due trial of the experiment which I have long desired."

This said, she kept silence. When F. I. (somewhat astonied with her strange speech) thus answered: "Mistress, although I cannot conceive the meaning of your words, yet by courtesy I am constrained to yield you thanks for your good will, the which appeareth no less in lamenting of mishaps than in rejoicing at good fortune. What experiment you mean to try by me, I know not, but I dare assure you that my skill in experiments is very simple."

Herewith the Instruments sounded a new Measure, and they passed forthwards, leaving to talk until the noise ceased: which done, the gentlewoman replied. "I am sorry sir, that you did erewhile deny love and all his laws, and that in so open audience."

"Not so," quoth F. I., "but as the word was roundly taken, so can I readily answer it by good reason."

"Well," quoth she, "how if the hearers will admit no reasonable answer?"

"My reason shall yet be nevertheless," quoth he, "in reasonable judgment." Herewith she smiled, and he cast a glance towards dame Ellinor askance, as who sayeth art thou pleased?

Again the viols called them forthwards, and again at the end of the braule said F. I. to this gentlewoman: "I pray you, Mistress, and what may be the second cause of your sorrow sustained in my behalf?"

"Nay, soft," quoth she, "percase I have not yet told you the first. But content yourself, for the second cause you shall never know at my hands until I see due trial of the experiment which I have long desired."

"Why then," quoth he, "I can but wish a present occasion to bring the same to effect, to the end that I might also understand the mystery of your meaning."

"And so might you fail of your purpose," quoth she, "for I mean to be better assured of him that shall know the depth of mine intent in such a secret than I do suppose that any creature (one except) may be of you."

"Gentlewoman," quoth he, "you speak Greek, the which I have now forgotten, and mine instructors are too far from me at this present to expound your words."

"Or else too near," quoth she, and so, smiling, stayed her talk when the music called them to another dance.

Which ended, F. I. half afraid of false suspect, and more amazed at this strange talk, gave over, and bringing Mistress Frances to her place was thus saluted by his Mistress. "Servant," quoth she, "I had done you great wrong to have danced with you, considering that this gentlewoman and you had former occasion of so weighty conference."

"Mistress," said F. I., "you had done me great pleasure, for by our conference I have but brought my brains in a busy conjecture."

"I doubt not," said his Mistress, "but you will end that business easily."

"It is hard," said F. I., "to end the thing whereof yet I have found no beginning."

His Mistress with change of countenance kept silence, whereat dame Frances, rejoicing, cast out this bone to gnaw on. "I perceive," quoth she,"it is evil to halt before a Cripple."[13]

F. I. perceiving now that his Mistress waxed angry, thought good on her behalf thus to answer: "And it is evil to hop before them that run for the Bell."

His Mistress replied, "And it is evil to hang the Bell at their heels which are always running."

The Lord of the Castle, overhearing these proper quips, rose out of his chair, and coming towards F. I.required him to dance a Galliard.

"Sir," said F. I., "I have hitherto at your appointment but walked about the house. Now, if you be desirous to see one tumble a turn or twain, it is like enough that I might provoke you to laugh at me. But in good faith, my dancing days are almost done, and therefore, sir," quoth he, "I pray you speak to them that are more nimble at tripping on the toe."

Whilst he was thus saying, dame Ellinor had made her Congé and was now entering the door of her chamber, when F. I., all amazed at her sudden departure, followed to take leave of his Mistress: but she, more then angry, refused to hear his good night, and entering her chamber caused her maid to clap the door.

F. I. with heavy cheer returned to his company, and Mistress Frances, to touch his sore with a corrosive, said to him softly in this wise. "Sir, you may now perceive that this our country cannot allow the French manner of dancing, for they (as I have heard tell) do more commonly dance to talk then entreat to dance."

F. I. hoping to drive out one nail with another[14], and thinking this a mean most convenient to suppress all jealous supposes, took Mistress Frances by the hand and with a heavy smile answered, "Mistress, and I (because I have seen the French manner of dancing) will eftsoons entreat you to dance a Barginet."

"What mean you by this?" quoth Mistress Frances.

"If it please you to follow," quoth he, "you shall see that I can jest without joy, and laugh without lust," and calling the musicians, caused them softly to sound the Tinternell, when he clearing his voice did Alla Napolitana[15] apply these verses following unto the measure:

|

[Nr 6] In prime of lusty years, when Cupid caught me in In prime of lusty years, when Cupid caught me in, With sweet enticing bait, I fish'd for many a dame, And smiling yet full oft, I have beheld that face, What will you more? So oft my gazing eyes did seek Then, all too late aghast, I did my foot retire, Or as the feeble sight would search the sunny beam, And since none other joy I had but her to see, Yet hope my comfort stay'd, that she would have regard The fairest Wolf will choose the foulest for her make, When floods of flowing tears had wash'd my weeping eyes, L'envoi. And when she saw by proof the pith of my good will, F. I. |

These verses are more in number than do stand with contentation of some judgments, and yet, the occasion thoroughly considered, I can commend them with the rest, for it is (as may be well termed)continua oratio, declaring a full discourse of his first love: wherein (over and besides that the Epithets are aptly applied & the verse of itself pleasant enough) I note that by it he meant in clouds to decipher unto Mistress Frances such matter as she would snatch at, and yet could take no good hold of the same. Furthermore, it answered very aptly to the note which the music sounded, as the skilful reader by due trial may approve.

This singing dance or dancing song ended, Mistress Frances, giving due thanks, seemed weary also of the company, and proffering to depart, gave yet this farewell to F. I., not vexed by choler, but pleased with contentation, and called away by heavy sleep: "I am constrained," quoth she, "to bid you good night," and so turning to the rest of the company, took her leave.

Then the Master of the house commanded a torch to light F. I. to his lodging, where (as I have heard him say) the sudden change of his Mistress' countenance together with the strangeness of Mistress Frances'talk made such an encounter in his mind that he could take no rest that night: wherefore in the morning rising very early, although it were far before his Mistress' hour, he cooled his choler by walking in the Gallery near to her lodging, and there in this passion compiled these verses following:

|

[Nr 7] A cloud of care hath cov'red all my coast A cloud of care hath cov'red all my coast[18] Before I sought, I found the haven of hap What may be said, where truth cannot prevail? F. I. |

This is but a rough meter, and reason, for it was devised in great disquiet of mind and written in rage, yet have I seen much worse pass the musters, yea, and where both the Lieutenant and Provost Marshall were men of ripe judgment[19]: and as it is I pray you let it pass here, for the truth is that F. I. himself had so slender liking thereof, or at least of one word escaped therein, that he never presented it -- but to the matter.

When he had long (and all in vain) looked for the coming of his Mistress into her appointed walk, he wand'red into the park near adjoining to the Castle wall, where his chance was to meet Mistress Francesaccompanied with one other Gentlewoman, by whom he passed with a reverence of curtsy: and so walking on, came into the side of a thicket, where he sat down under a tree to allay his sadness with solitariness.

Mistress Frances, partly of courtesy and affection, and partly to content her mind by continuance of such talk as they had commenced over night, entreated her companion to go with her unto this tree of reformation, whereas they found the Knight with his arms unfolded in a heavy kind of contemplation, unto whom Mistress Frances stepped apace (right softly) & at unwares gave this salutation. "I little thought Sir Knight," quoth she, "by your evensong yesternight to have found you presently at such a morrow mass, but I perceive you serve your Saint with double devotion; and I pray God grant you treble meed for your true intent."

F. I., taken thus upon the sudden, could none otherwise answer but thus: "I told you, Mistress," quoth he, "that I could laugh without lust and jest without joy." And there withal starting up, with a more bold countenance came towards the Dames, proffering unto them his service, to wait upon them homewards.

"I have heard say oft times," quoth Mistress Frances, "that it is hard to serve two Masters at one time, but we will be right glad of your company."

"I thank you," quoth F. I., and so, walking on with them, fell into sundry discourses, still refusing to touch any part of their former communication, until Mistress Frances said unto him:

"By my troth," quoth she, "I would be your debtor these two days, to answer me truly but unto one question that I will propound."

"Fair Gentlewoman," quoth he, "you shall not need to become my debtor, but if it please you to quit question by question, I will be more ready to gratify you in this request than either reason requireth or than you would be willing to work my contentation."

"Master F. I.," quoth she, & that sadly, "peradventure you know but a little how willing I would be to procure your contentation. But you know that hitherto familiarity hath taken no deep root betwixt us twain. And though I find in you no manner of cause whereby I might doubt to commit this or greater matter unto you, yet have I stayed hitherto so to do in doubt least you might thereby justly condemn me both of arrogancy and lack of discretion, wherewith I must yet foolishly affirm that I have with great pain bridled my tongue from disclosing the same unto you. Such is then the good will that I bear towards you, the which if you rather judge to be impudency than a friendly meaning, I may then curse the hour that I first concluded thus to deal with you."

Herewithal being now red for chaste bashfulness, she abased her eyes and stayed her talk, to whom F. I.thus answered: "Mistress Frances, if I should with so exceeding villainy requite such and so exceeding courtesy, I might not only seem to degenerate from all gentry but also to differ in behavior from all the rest of my life spent: wherefore to be plain with you in few words, I think myself so much bound unto you for divers respects, as if ability do not fail me, you shall find me mindful in requital of the same: and for disclosing your mind to me, you may if so please you adventure it without adventure, for by this Sun," quoth he, "I will not deceive such trust as you shall lay upon me, and furthermore, so far forth as I may, I will be yours in any respect: wherefore I beseech you accept me for your faithful friend, and so shall you surely find me."

"Not so," quoth she, "but you shall be my Trust, if you vouchsafe the name, and I will be to you as you shall please to term me."

"My Hope," quoth he, "if you so be pleased."

And thus agreed they two walked apart from the other Gentlewoman, and fell into sad talk, wherein Mistress Frances did very courteously declare unto him, that indeed, one cause of her sorrow sustained in his behalf was that he had said so openly over night that he could not love, for she perceived very well the affection between him and Madame Ellinor, and she was also advertised that Dame Ellinor stood in the portal of her chamber hearkening to the talk that they had at supper that night, wherefore she seemed to be sorry that such a word (rashly escaped) might become great hindrance unto his desire: but a greater cause of her grief was (as she declared) that his hap was to bestow his liking so unworthily, for she seemed to accuse Dame Ellinor for the most unconstant woman living.

In full proof whereof, she bewrayed unto F. I. how she the same Dame Ellinor, had of long time been yielded to the Minion Secretary whom I have before described, "in whom though there be," quoth she, "no one point of worthiness, yet shameth she not to use him as her dearest friend, or rather her holiest Idol," and that this not withstanding, Dame Ellinor had been also sundry times won to choice of change, as she named unto F. I. two Gentlemen, whereof the one was named H. D. and that other H. K., by whom she was during sundry times of their several abode in those parts entreated to like courtesy, for these causes the Dame Frances seemed to mislike F. I.'s choice, and to lament that she doubted in process of time to see him abused.

The experiment she meant was this: for that she thought F. I. (I use her words) a man in every respect very worthy to have the several use of a more commodious common[20], she hoped now to see if his enclosure thereof might be defensible against her said Secretary, and such like. These things and divers other of great importance this courteous Lady Frances did friendly disclose unto F. I., and furthermore did both instruct and advise him how to proceed in his enterprise.

Now to make my talk good, and lest the Reader might be drawn in a jealous suppose of this LadyFrances, I must let you understand that she was unto F. I. a kinswoman, a virgin of rare chastity, singular capacity, notable modesty, and excellent beauty: and though F. I. had cast his affection on the other (being a married woman), yet was there in their beauties no great difference: but in all other good gifts a wonderful diversity, as much as might be between constancy & flitting fantasy, between womanly countenance & girlish garishness, between hot dissimulation & temperate fidelity. Now, if any man will curiously ask the question why F. I. should choose the one and leave the other, over and besides the common proverb So many men so many minds, thus may be answered: We see by common experience that the highest flying falcon doth more commonly prey upon the corn fed crow & the simple shiftless dove than on the mounting kite. And why? Because the one is overcome with less difficulty then that other.

Thus much in defense of this Lady Frances & to excuse the choice of my friend F. I., who thought himself now no less beholding to good fortune to have found such a trusty friend then bounden to Dame Venusto have won such a Mistress.

And to return unto my pretence, understand you that F. I. (being now with these two fair Ladies come very near the castle) grew in some jealous doubt (as on his own behalf) whether he were best to break company or not. When his assured Hope, perceiving the same, gan thus recomfort him: "Good sir," quoth she, "if you trusted your trusty friends, you should not need thus cowardly to stand in dread of your friendly enemies."

"Well said, in faith," quoth F. I., "and I must confess, you were in my bosom before I wist; but yet I have heard said often that in trust is treason."

"Well spoken for yourself," quoth his Hope.

F. I., now remembering that he had but erewhile taken upon him the name of her Trust, came home per misericordiam[21], when his Hope, entering the Castle gate, caught hold of his lap and half by force led him by the gallery unto his Mistress chamber, whereas after a little dissembling disdain, he was at last by the good help of his Hope right thankfully received. And for his Mistress was now ready to dine, he was therefore for that time arrested there & a supersedias sent into the great chamber unto the Lord of the house, who expected his coming out of the park.

The dinner ended, & he thoroughly contented both with welfare & welcome, they fell into sundry devices of pastime. At last F. I. taking into his hand a Lute that lay on his Mistress bed, did unto the note of theVenetian galliard apply the Italian ditty written by the worthy Bradamant unto the noble Rugier (asAriosto hath it, Rugier qual semper fui, &c.[22]). But his Mistress could not be quiet until she heard him repeat the Tinternell which he used over night, the which F. I. refused not; at end whereof his Mistress thinking now she had showed herself too earnest to use any further dissimulation, especially perceiving the toward inclination of her servant's Hope, fell to flat plain dealing, and walking to the window, called her servant apart unto her, of whom she demanded secretly & in sad earnest, who devised thisTinternell?

"My Father's sister's brother's son," quoth F. I..

His Mistress laughing right heartily, demanded yet again, by whom the same was figured.

"By a niece to an Aunt of yours, Mistress," quoth he.

"Well then, servant," quoth she, "I swear unto you here by my Father's soul, that my mother's youngest daughter doth love your father's eldest son above any creature living."

F. I. hereby recomforted, gan thus reply. "Mistress, though my father's eldest son be far unworthy of so noble a match, yet since it pleaseth her so well to accept him, I would thus much say behind his back, that your mother's daughter hath done him some wrong."

"& wherein, servant?" quoth she.

"By my troth, Mistress," quoth he, "it is not yet 20 hours since without touch of breast she gave him such a nip by the heart as did altogether bereave him his night's rest with the bruise thereof."

"Well, servant," quoth she, "content yourself, and for your sake, I will speak to her to provide him a plaster, the which I myself will apply to his hurt. And to the end it may work the better with him, I will purvey a lodging for him where hereafter he may sleep at more quiet." This said, the rosy hue destained her sickly cheeks, and she returned to the company, leaving F. I. ravished between hope and dread, as one that could neither conjecture the meaning of her mystical words nor assuredly trust unto the knot of her sliding affections.

When the Lady Frances coming to him demanded, "What? dream you sir?"

"Yea, marry, do I, fair Lady," quoth he.

"And what was your dream, sir," quoth she?

"I dreamt," quoth F. I., "that walking in a pleasant garden garnished with sundry delights, my hap was to espy hanging in the air a hope wherein I might well behold the aspects and face of the heavens, and calling to remembrance the day and hour of my nativity, I did thereby (according to my small skill in Astronomy) try the conclusions of mine adventures."

"And what found you therein," quoth dame Frances?

"You awaked me out of my dream," quoth he, "or else peradventure you should not have known."

"I believe you well," quoth the Lady Frances, and laughing at his quick answer brought him by the hand unto the rest of his company: where he tarried not long before his gracious Mistress bade him to fare well and to keep his hour there again when he should by her be summoned.

Hereby F. I. passed the rest of that day in hope awaiting the happy time when his Mistress should send for him. Supper time came and passed over, and not long after came the handmaid of the Lady Ellinor into the great chamber, desiring F. I. to repair unto their Mistress, the which he willingly accomplished: and being now entered into her chamber, he might perceive his Mistress in her nights attire preparing herself towards bed, to whom F. I. said: "Why how now, Mistress? I had thought this night to have seen you dance (at least or at last) amongst us?"

"By my troth, good servant," quoth she, "I adventured so soon unto the great chamber yesternight that I find myself somewhat sickly disposed, and therefore do strain courtesy, as you see, to go the sooner to my bed this night. But before I sleep," quoth she, "I am to charge you with a matter of weight," and taking him apart from the rest, declared that (as that present night) she would talk with him more at large in the gallery near adjoining to her chamber.

Here upon F. I., discretely dissimuling his joy, took his leave and returned into the great chamber, where he had not long continued before the Lord of the Castle commanded a torch to light him unto his lodging, whereas he prepared himself and went to bed, commanding his servant also to go to his rest.

And when he thought as well his servant as the rest of the household to be safe, he arose again, & taking his nightgown, did under the same convey his naked sword[23], and so walked to the gallery, where he found his good Mistress walking in her nightgown and attending his coming. The Moon was now at the full, the skies clear, and the weather temperate, by reason whereof he might the more plainly and with the greater contentation behold his long desired joys, and spreading his arms abroad to embrace his loving Mistress, he said: "Oh, my dear Lady, when shall I be able with any desert to countervail the least part of this your bountiful goodness?"

The dame (whether it were of fear indeed, or that the wiliness of womanhood had taught her to cover her conceits with some fine dissimulation) stert back from the Knight, and shrieking (but softly), said unto him, "Alas, servant, what have I deserved, that you come against me with naked sword as against an open enemy?"

F. I. perceiving her intent, excused himself, declaring that he brought the same for their defense & not to offend her in any wise. The Lady being therewith somewhat appeased, they began with more comfortable gesture to expel the dread of the said late affright, and sithens to become bolder of behavior, more familiar in speech, & most kind in accomplishing of common comfort.

But why hold I so long discourse in describing the joys which (for lack of like experience) I cannot set out to the full? Were it not that I know to whom I write, I would the more beware what I write. F. I. was a man, and neither of us are senseless, and therefore I should slander him (over and besides a greater obloquy to the whole genealogy of Enaeas) if I should imagine that of tender heart he would forbear to express her more tender limbs against the hard floor. Sufficed that of her courteous nature she was content to accept boards for a bead of down, mats for Cambric sheets, and the nightgown of F. I. for a counterpoint to cover them, and thus with calm content in stead of quiet sleep, they beguiled the night, until the proudest star began to abandon the firmament, when F. I. and his Mistress, were constrained also to abandon their delights, and with ten thousand sweet kisses and straight embracings did frame themselves to play loath to depart.

Well, remedy was there none, but dame Ellinor must return unto her chamber, and F. I. must also convey himself (as closely as might be) into his chamber, the which was hard to do, the day being so far sprung and he having a large base court to pass over before he could recover his stair foot door. And though he were not much perceived, yet the Lady Frances, being no less desirous to see an issue of these enterprises then F. I. was willing to cover them in secrecy, did watch, & even at the entering of his chamber door, perceived the point of his naked sword glist'ring under the skirt of his night gown: whereat she smiled & said to her self, this gear goeth well about.

Well, F. I. having now recovered his chamber, he went to bed, & there let him sleep, as his Mistress did on that other side. Although the Lady Frances being thoroughly tickled now in all the veins, could not enjoy such quiet rest, but arising, took another gentlewoman of the house with her and walked into the park to take the fresh air of the morning. They had not long walked there, but they returned, and thoughF. I. had not yet slept sufficiently for one which had so far travailed in the night past, yet they went into his chamber to raise him, and coming to his beds side, found him fast on sleep.

"Alas," quoth that other gentlewoman, "it were pity to awake him."

"Even so it were," quoth dame Frances, "but we will take away somewhat of his, whereby he may perceive that we were here," and looking about the chamber, his naked sword presented itself to the hands of dame Frances, who took it with her, and softly shutting his chamber door again, went down the stairs and recovered her own lodging in good order and unperceived of any body, saving only that other gentlewoman which accompanied her.

At the last, F. I. awaked, and appareling himself, walked out also to take the air, and being thoroughly recomforted as well with remembrance of his joys forepassed, as also with the pleasant harmony which the Birds made on every side and the fragrant smell of the redolent flowers and blossoms which budded on every branch, he did in these delights compile these verses following.

The occasion (as I have heard him rehearse) was by encounter that he had with his Lady by light of the moon: and forasmuch as the moon in midst of their delights did vanish away, or was overspread with a cloud, thereupon he took the subject of his theme. And thus it ensueth, called "A Moonshine Banquet." [24]

|

[Nr 8] Dame Cynthia herself that shines so bright Dame Cynthia herself (that shines so bright Good reason yet that to my simple skill, Dan Phoebus he with many a low'ring look, And thus when many a look had lookt so long, Wherefore at better leisure thought I best The courteous Moon that wisht to do me good F. I. |

This Ballad, or howsoever I shall term it, percase you will not like, and yet in my judgment it hath great good store of deep invention, and for the order of the verse, it is not common, I have not heard many of like proportion. Some will account it but a dyddeldeme: but who so had heard F. I. sing it to the lute by a note of his own devise, I suppose he would esteem it to be a pleasant diddeldome, and for my part, if I were not partial, I would say more in commendation of it than now I mean to do, leaving it to your and like judgments.

And now to return to my tale, by that time that F. I. returned out of the park, it was dinner time, and at dinner they all met, I mean both dame Ellinor, dame Frances, and F. I.. I leave to describe that the LadyFrances was gorgeously attired and set forth with very brave apparel, and Madame Ellinor only in her night gown girt to her, with a coif trimmed Alla Piedmonteze, on the which she wore a little cap crossed over the crown with two bends of yellow Sarcenet or Cypress, in the midst whereof she had placed, of her own handwriting, in paper this word, Contented. This attire pleased her then to use, and could not have displeased Mistress Frances, had she not been more privy to the cause than to the thing itself: at least the Lord of the Castle (of ignorance) and dame Frances (of great temperance) let it pass without offence. At dinner, because the one was pleased with all former reckonings, and the other made privy to the account, there passed no word of taunt or grudge, but omnia bene.[25]

After dinner, dame Ellinor being no less desirous to have F. I. company than dame Frances was to take him in some pretty trip, they began to question how they might best pass the day: the Lady Ellinorseemed desirous to keep her chamber, but Mistress Frances for another purpose seemed desirous to ride abroad thereby to take the open air. They agreed to ride a mile or twain for solace, and requested F. I.to accompany them, the which willingly granted.

Each one parted from other to prepare themselves, and now began the sport, for when F. I. was booted, his horses saddled, and he ready to ride, he gan miss his Rapier. Whereat all astonied he began to blame his man, but blame whom he would, found it could not be. At last, the Ladies going towards horseback called for him in the base Court and demanded if he were ready. To whom F. I. answered, "Madames, I am more than ready and yet not so ready as I would be," and immediately taking himself in trip, he thought best to utter no more of his conceit, but in haste more than good speed mounted his horse, & coming toward the dames presented himself, turning, bounding, & taking up his courser to the uttermost of his power in bravery. After suffering his horse to breathe himself, he gan also allay his own choler, & to the dames he said, "Fair Ladies, I am ready when it pleaseth you to ride where so you command."

"How ready soever you be, servant," quoth dame Ellinor, "it seemeth your horse is readier at your command then at ours."

"If he be at my command, Mistress," quoth he, "he shall be at yours."

"Gramercy, good servant," quoth she, "but my meaning is that I fear he be too stirring for our company." [26]

"If he prove so, Mistress," quoth F. I., "I have here a soberer palfrey to serve you on."

The Dames being mounted, they rode forthwards by the space of a mile or very near, and F. I. (whether it were of his horse's courage or his own choler) came not so near them as they wished. At last the LadyFrances said unto him, "Master I., you said that you had a soberer horse, which if it be so, we would be glad of your company. But I believe by your countenance, your horse & you are agreed."

F. I., alighting, called his servant, changed horses with him, and overtaking the Dames, said to MistressFrances: "And why do you think, fair Lady, that my horse and I are agreed?"

"Because by your countenance," quoth she, "it seemeth your patience is stirred."

"In good faith," quoth F. I., "you have guessed a right, but not with any of you."

"Then we care the less, servant," quoth Dame Ellinor.

"By my troth, Mistress," quoth F. I. (looking well about him that none might hear but they two), "it is with my servant, who hath lost my sword out of my chamber."

Dame Ellinor, little remembering the occasion, replied, "It is no matter, servant," quoth she, "you shall hear of it again, I warrant you, and presently we ride in God's peace and I trust shall have no need of it."

"Yet Mistress," quoth he, "a weapon serveth both uses, as well to defend as to offend."

"Now by my troth," quoth Dame Frances, "I have now my dream, for I dreamt this night that I was in a pleasant meadow alone, where I met with a tall Gentleman apparelled in a nightgown of silk all embroidered about with a guard of naked swords, and when he came towards me I seemed to be afraid of him, but he recomforted me saying, 'Be not afraid fair Lady, for I use this garment only for mine own defense: and in this sort went that warlike God Mars what time he taught dame Venus to make Vulcan a hammer of the new fashion.' [27] Notwithstanding these comfortable words, the fright of the dream awaked me, and sithens unto this hour I have not slept at all."

"And what time of the night dreamt you this?" quoth F. I.

"In the grey morning, about dawning of the day. But why ask you?" quoth dame Frances.

F. I. with a great sigh answered, "Because that dreams are to be marked more at some hour of the night then at some other."

"Why are you so cunning at the interpretation of dreams, servant?" quoth the Lady Ellinor.

"Not very cunning, Mistress," quoth F. I., "but guess, like a young scholar."

The dames continued in these and like pleasant talks: but F. I. could not be merry, as one that esteemed the preservation of his Mistress' honor no less then the obtaining of his own delights: and yet to avoid further suspicion, he repressed his passions as much as he could.

The Lady Ellinor, more careless then considerative of her own case, pricking forwards said softly to F. I., "I had thought you had received small cause, servant, to be thus dumpish when I would be merry."

"Alas, dear Mistress," quoth F. I., "it is altogether for your sake that I am pensive."

Dame Frances with courtesy withdrew herself and gave them leave. When as F. I. declared unto his Mistress that his sword was taken out of his chamber, and that he dreaded much by the words of the Lady Frances that she had some understanding of the matter.

Dame Ellinor now calling to remembrance what had passed the same night, at the first was abashed, but immediately (for these women be readily witted) cheered her servant and willed him to commit unto her the salving of that sore. Thus they passed the rest of the way in pleasant talk with dame Frances, and so returned towards the Castle where F. I. suffered the two dames to go together, and he alone unto his chamber to bewail his own misgovernment.

But dame Ellinor (whether it were according to old custom or by wily policy) found mean that night that the sword was conveyed out of Mistress Frances' chamber and brought unto hers, and after redelivery of it unto F. I., she warned him to be more wary from that time forthwards.

Well, I dwell too long upon these particular points in discoursing this trifling history, but that the same is the more apt mean of introduction to the verses which I mean to rehearse unto you, and I think you will not disdain to read my conceit with his invention about declaration of his comedy. The next that ever F. I. wrote then upon any adventure happened between him and this fair Lady, was this, as I have heard him say, and upon this occasion. After he grew more bold & better acquainted with his Mistress' disposition, he adventured one Friday in the morning to go unto her chamber, and thereupon wrote as followeth, which he termed "A Friday's Breakfast."

|

[Nr 9] That selfsame day, and of that day that hour That selfsame day, and of that day that hour, F. I. |

This Sonnet is short and sweet, reasonably well, according to the occasion &c.

Many days passed these two lovers with great delight, their affairs being no less politicly governed than happily achieved. And surely I have heard F. I. affirm in sad earnest that he did not only love her, but was furthermore so ravished in Ecstasies with continual remembrance of his delights that he made an Idol of her in his inward conceit. So seemeth it by this challenge to beauty[29], which he wrote in her praise and upon her name.

|

[Nr 10] Beauty, shut up thy shop and truss up all thy trash Beauty, shut up thy shop and truss up all thy trash, F. I. |

By this challenge, I guess that either he was then in an ecstasy or else sure I am now in a lunacy, for it is a proud challenge made to Beauty herself and all her companions, and imagining that Beauty having a shop where she uttered her wares of all sundry sorts, his Lady had stolen the finest away, leaving none behind her but painting, bolstering, forcing, and such like, the which in his rage he judgeth good enough to serve the Court. And thereupon grew a great quarrel when these verses were by the negligence of his Mistress dispersed into sundry hands, and so at last to the reading of a Courtier.

Well, F. I. had his desire if his Mistress liked them, but as I have heard him declare, she grew in jealousy that the same were not written by her, because her name was Ellinor and not Helen. And about this point have been divers and sundry opinions, for this and divers other of his most notable Poems have come to view of the world, although altogether without his consent. And some have attributed this praise unto aHelen, who deserved not so well as this dame Ellinor should seem to deserve by the relation of F. I., and yet never a barrel of good herring between them both.[31] But that other Helen, because she was and is of so base condition as may deserve no manner commendation in any honest judgment, therefore I will excuse my friend F. I. and adventure my pen in his behalf, that he would never bestow verse of so mean a subject. And yet some of his acquaintance, being also acquainted (better than I) that F. I. was sometimes acquainted with Helen, have stood in argument with me, that it was written by Helen and not by Ellinor. Well, F. I. told me himself that it was written by this dame Ellinor, and that unto her he thus alleged, that he took it all for one name, or at least he never read of any Ellinor such matter as might sound worthy like commendation for beauty. And indeed, considering that it was in the first beginning of his writings, as then he was no writer of any long continuance, comparing also the time that such reports do spread of his acquaintance with Helen, it cannot be written less then six or seven years before he knew Helen. Marry, peradventure if there were any acquaintance between F. I. and that Helen afterwards (the which I dare not confess), he might adapt it to her name and so make it serve both their turns, as elder lovers have done before and still do and will do world without end. Amen.

Well, by whom he wrote it, I know not, but once I am sure that he wrote it, for he is no borrower of inventions, and this is all that I mean to prove, as one that send you his verses by stealth and do him double wrong to disclose unto any man the secret causes why they were devised, but this for your delight I do adventure, and to return to the purpose, he sought more certainly to please his MistressEllinor with this Sonnet written in her praise as followeth.

|

[Nr 11] The stately Dames of Rome their Pearls did wear The stately Dames of Rome their Pearls did wear F. I. |

Of this Sonnet, I am assured that it is but a translation, for I myself have seen the invention of an Italian[32], and Master I. hath a little dilated the same, but not much besides the sense of the first, and the addition very aptly applied: wherefore I cannot condemn his doing therein. And for the Sonnet, were it not a little too much praise (as the Italians do most commonly offend in the superlative), I could the more commend it: but I hope the party to whom it was dedicated had rather it were much more than any thing less.

Well, thus these two Lovers passed many days in exceeding contentation & more than speakable pleasures, in which time F. I. did compile very many verses according to sundry occasions proffered, whereof I have not obtained the most at his hands. And the reason that he denied me the same was that (as he alleged) they were for the most part sauced with a taste of glory, as you know that in such cases, a lover being charged with inexprimable joys, and therewith enjoined both by duty and discretion to keep the same covert, can by no means devise a greater consolation than to commit it into some ciphered words and figured speeches in verse, whereby he feeleth his heart half (or more than half) eased of swelling. For as sighs are some present ease to the pensive mind, even so we find by experience that such secret entercomoning of joys doth increase delight.

I would not have you conster my words to this effect, that I think a man cannot sufficiently rejoice in the lucky lots of love unless he impart the same to others. God forbid that ever I should enter into such an heresy, for I have always been of this opinion, that as to be fortunate in love is one of the most inward contentatious to man's mind of all earthly joys: even so, if he do but once bewray the same to any living creature, immediately either dread of discovering doth bruise his breast with an intolerable burden, or else he leeseth the principal virtue which gave effect to his gladness, not unlike to a 'pothecaries pot which, being filled with sweet ointments or perfumes, doth retain in itself some scent of the same, and being poured out doth return to the former state, hard, harsh, and of small savour. So the mind being fraught with delights, as long as it can keep them secretly enclosed, may continually feed upon the pleasant record thereof, as the well willing and ready horse biteth on the bridle, but having once disclosed them to any other, straightway we lose the hidden treasure of the same and are oppressed with sundry doubtful opinions and dreadful conceits. And yet for a man to record unto himself in the inward contemplation of his mind the often remembrance of his late received joys doth, as it were, ease the heart of burden and add unto the mind a fresh supply of delight, yea, and in verse principally (as I conceive), a man may best contrive this way of comfort in himself.

Therefore, as I have said, F. I. swimming now in delights did nothing but write such verse as might accumulate his joys to the extremity of pleasure, the which for that purpose he kept from me, as one more desirous to seem obscure and defective than overmuch to glory in his adventures, especially for that in the end his hap was as heavy as hitherto he had been fortunate. Amongst other, I remembered one happened upon this occasion:

The husband of the Lady Ellinor, being all this while absent from her, gan now return, & kept Cut at home, with whom F. I. found means so to insinuate himself that familiarity took deep root between them and seldom but by stealth you could find the one out of the other's company. On a time, the knight riding on hunting, desired F. I. to accompany him, the which he could not refuse to do, but like a lusty younker, ready at all assays, apparelled himself in green, and about his neck a Bugle, pricking & galloping amongst the foremost according to the manner of that country. And it chanced that the married Knight thus galloping lost his horn, which some divines might have interpreted to be but molting, & that by Gods grace, he might have a new come up again shortly in stead of that. Well, he came to F. I., requiring him to lend him his Bugle, for (said the Knight) "I heard you not blow this day, and I would fain encourage the hounds, if I had a horn."

Quoth F. I., "Although I have not been over lavish of my coming hitherto, I would you should not doubt but that I can tell how to use a horn well enough, and yet I may little do if I may not lend you a horn," and therewithal took his Bugle from his neck and lent it to the Knight, who making in unto the hounds, gan assay to rechat: but the horn was too hard for him to wind, whereat F. I. took pleasure and said to himself, "Blow till thou break that: I made thee one within these few days that thou wilt never crack whiles thou livest." And hereupon (before the fall of the Buck) devised this Sonnet following, which at his homecoming he presented unto his Mistress.

|

[Nr 12] As some men say there is a kind of seed As some men say there is a kind of seed[33] F. I. |