5.2.1. Poems 1 - 63 (1572-1575)

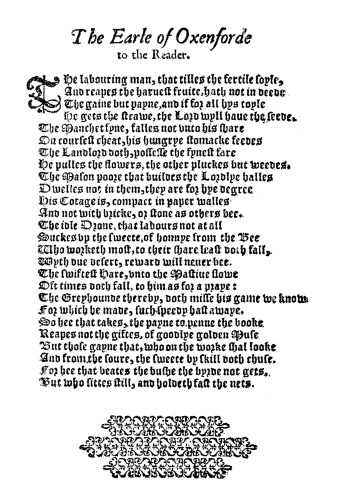

THE EARL OF OXFORD TO THE READER (1572-1573)

1. The labouring man that tills the fertile soil

The Earl of Oxford to the Reader

The labouring man that tills the fertile soil,

And reaps the harvest fruit, hath not indeed

The gain, but pain, and if for all his toil

He gets the straw, the Lord will have the seed.

The manchet fine falls not unto his share,

On coarsest cheat his hungry stomach feeds,

The landlord doth possess the finest fare,

He pulls the flowers, th’ other plucks but weeds.

The mason poor that builds the lordly halls,

Dwells not in them, they are for high degree,

His cottage is compact in paper walls,

And not with brick or stone, as others be.

The idle drone that labours not at all,

Sucks up the sweet of honey from the bee;

Who worketh most to their share least doth fall,

With due desert reward will never be.

The swiftest hare unto the mastiff slow

Oft-times doth fall, to him as for a prey:

The greyh’nd thereby doth miss his game we know

For which he made such speedy haste away.

So he that takes the pain to pen the book,

Reaps not the gifts of goodly golden muse,

But those gain that, who on the work shall look

And from the sour the sweet by skill doth choose.

For he that beats the bush the bird not gets,

But who sits still and holdeth fast the nets.

Source: Cardanus Comforte, 1573

Introductory poem to Girolamo Cardanos' “Book of Consolation” (De Consolatione, Venezia 1542). Sir Thomas Bedingfield dated his translation of this work at January 1572 . However the book was not published until 1573. Thomas Bedingfield (c.1540 -1613) was one of Oxford’s best friends; in July 1574, on the orders of the Queen, Bedingfield searched in Flanders for the young Earl, caught him up in Zaltbommel on the river Waal and accompanied him to London.

Edmund Spenser (1552–1599) didn’t neglect the opportunity to feature the Earl of Oxford in his first work: The Shepheardes Calender (1580). The summary of the “Aegloga decima” (eclogue of October) begins:

In Cuddie is set out the perfect pattern of a Poet, which finding no maintenance of his state and studies, complayneth of the contempt of Poetry, and the causes thereof.

Spenser lets Cuddie say:

CUDDIE. To feed youthes fancy, and the flocking fry,

Delighten much: what I the bet for thy?

They han the pleasure, I a slender prise.

I beat the bush, the birds to them doe flie:

What good thereof to Cuddie can arise?

Another shepherd, Pierce answers: “Cuddie, the praise is better then the price, / The glory eke much greater then the gain.”

A HUNDRETH SUNDRIE FLOWRES (1573)

2. To scourge the crime of wicked Laius

JOCASTA. The argument of the Tragedy.

To scourge the crime of wicked Laius[1],

And wreak the foul incest of Oedipus,

The angry Gods stirred up their sons, by strife

With blades embrewed to reave each others life:

The wife, the mother, and the concubine[2],

(Whose fearful heart foredread their fatal fine,)

Her sons thus dead, disdaineth longer life,

And slays herself with selfsame bloody knife:

The daughter she, surprised with childish dread[3]

(That durst not die) a loathsome life doth lead,

Yet rather chose to guide her banished sire,

Than cruel Creon should have his desire.

Creon is King, the type of tyranny,

And Oedipus, mirror of misery.

Fortunatus Infoelix.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres chapt.II (Jocasta), 1573

Poetical prologue to George Gasgoignes “Jocasta”, a free translation of Euripides' “Phoenician Women”. Gascoigne's work (after Ludovico Dolces adaption “Giocasta”, 1549) was premièred on the stage of the the legal faculty of Grey's Inn in 1566. - There is only one other work in the English literature of the 16th century, using poetry in sonnet form for the prologue: “Two households, both alike in dignity”. The play in question is: Romeo and Juliet (Chorus).

Two households both alike in dignity

(In fair Verona, where we lay our scene)

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life,

Whose misadventur'd piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents' strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark'd love

And the continuance of their parents' rage,

Which, but their children's end, naught could remove,

Is now the two hours' traffic of our stage;

The which if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

Oxford often made use of the sonnet form (with free variations on the rhyme patterns) as in numbers 4, 9, 11, 12, 15, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 36, 39, 47, 57, 60, 87, 92, 93, 98.

THE ADVENTURES OF MASTER F. I. (1573)

The poems of “F. I.” make up the fiery nucleus of The Adventures of Master F[ortunatus] I[infoelix]. In a manner that reminds of how Dante's poems made up basis for the novella La Vita Nuova (1293).

3. Fair Bersabe the bright once bathing in a well

I have heard the Author say, that these were the first verses that ever

he wrote upon like occasion.

Fair Bersabe the bright, once bathing in a well[4],

With dew bedimm’d King David’s eyes that ruled Israel,

And Salomon himself, the source of sapience[5],

Against the force of such assaults could make but small defense:

To it the stoutest yield, and strongest feel like woe,

Bold Hercules and Samson both did prove it to be so.

What wonder seemeth then, when stars stand thick in skies,

If such a blazing star have power to dim my dazzled eyes?

L'envoy.

To you these few suffice, your wits be quick and good,

You can conject by change of hue, what humors feed my blood.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

Master F. I. manages the rickety, bumpy “poulter's metre” without serious injury (see also Nos. 17, 24, 25, 30, 41, 43, 44, 46, 50, 56, 59, 76, 77). The term “poulter's metre” is a play on the practice employed by poulterers of selling eggs by the dozen, giving the customer two eggs as a bonus. The number fourteen became known as “The poulter's dozen”.

Sternhold and Hopkins used the poulter's metre for the popular re-writes of the psalms in the fifties and the sixties of the sixteenth century (The Whole Boke of Psalmes, collected into Englishe metre by Thomas Sternhold, I. Hopkins, and others). Infuriated by there choice C.S. Lewis said: “The vices of that metre are two. The medial break in the alexandrine, though it may well do in French, quickly becomes intolerable in a language with such a tyrannous stress-accent as ours: the line struts. The fourteener has a much pleasanter movement, but a totally different one; the line dances a jig. Hence in a couplet made of two such yoke-fellows we seem to be labouring up a steep hill in bottom gear for the first line, and then running down the other side of the hill, out of control, for the second.“ (English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, 1954, p. 232-33.)

4. Of thee dear Dame, three lessons would I learn

Terza sequenza, to sweet Mistress SHE.

Of thee dear Dame, three lessons would I learn[6]:

What reason first persuades the foolish fly

(As soon as she a candle can discern)

To play with flame, till she be burnt thereby?

Or what may move the mouse to bite the bait

Which strikes the trap, that stops her hungry breath?

What calls the bird, where snares of deep deceit

Are closely couched to draw her to her death?

Consider well, what is the cause of this,

And though percase thou wilt not so confess,

Yet deep desire, to gain a heavenly bliss,

May drown the mind in dole and dark distress:

Oft is it seen (whereat my heart may bleed)

Fools play so long till they be caught in deed.

And then

It is a heaven to see them hop and skip,

And seek all shifts to shake their shackles off:

It is a world, to see them hang the lip,

Who (erst) at love, were wont to scorn and scoff.

But as the mouse, once caught in crafty trap,

May bounce and beat against the boarden wall,

Till she have brought her head in such mishap

That down to death her fainting limbs must fall:

And as the fly once singed in the flame,

Cannot command her wings to wave away:

But by the heel, she hangeth in the same

Till cruel death her hasty journey stay:

So they that seek to break the links of love

Strive with the stream, and this by pain I prove.

For when

I first beheld that heavenly hue of thine,

Thy stately stature and thy comely grace,

I must confess these dazzled eyes of mine

Did wink for fear, when I first view’d thy face:

But bold desire did open them again,

And bad me look till I had looked too long,

I pitied them that did procure my pain,

And lov'd the looks that wrought me all the wrong:

And as the bird once caught (but works her woe)

That strives to leave the limed twigs behind:

Even so the more I strave to part thee fro,

The greater grief did grow within my mind:

Remediless then must I yield to thee,

And crave no more thy servant but to be.

Till then and ever. HE.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

The first narrative sonnet sequence (made up of three sonnets = terza sequenza) in the English language See, Poems No. 57 “This Apuleius was in Afric born”.

5. Love, hope, and death, do stir in me such strife

I have heard F. I. say that he borrowed th'invention of an Italian: but, were it

a translation or invention, (if I be judge) it is both pretty and pithy.

Love, hope, and death, do stir in me such strife,

As never man but I led such a life.

First burning love doth wound my heart to death,

And when death comes at call of inward grief,

Cold lingering hope doth feed my fainting breath

Against my will, and yields my wound relief:

So that I live, but yet my life is such,

As death would never grieve me half so much.

No comfort then but only this I taste,

To salve such sore, such hope will never want,

And with such hope, such life will ever last,

And with such life, such sorrows are not scant.

O strange desire, O life with torments tost

Through too much hope mine only hope is lost.

Even HE.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

This poem shows similarities to Petrarch, Canzoniere 184 (“Amor, Natura, et la bella alma humile”).

Love, Nature, and the lovely gentle soul,

where every noble virtue lives and reigns,

conspire against me now: Love racks his brains

to bring me to my death (his usual style);

Nature by bonds so slight to earth confines

Her slender form, a breath may break its chains;

And she, so much her heart the world disdains,

Longer to tread life's wearying round repines…

(Transl. by A. S. Kline / Th. Campbell)

The particular poetical device in Oxford’s poem is known as anadiplosis, the repetition of the last word of a preceding clause (sore / hope / life / sorrows). See also, Nos. 31, 92 and 110.

6. In prime of lusty years, when Cupid caught me in

These verses are more in number than do stand with contentation of some judgments, and yet, the occasion thoroughly considered, I can commend them with the rest, for it is (as may be well termed) continua oratio, declaring a full discourse of his first love.

In prime of lusty years, when Cupid caught me in,

And nature taught the way to love, how I might best begin

To please my wand'ring eye in beauty’s tickle trade,

To gaze on each that passed by, a careless sport I made.

With sweet enticing bait I fish'd for many a dame,

And warméd me by many a fire, yet felt I not the flame:

But when at last I spied the face that please me most,

The coals were quick, the wood was dry, & I began to toast.

And smiling yet full oft, I have beheld that face[7],

When in my heart I might bewail mine own unlucky case,

And oft again with looks that might bewray my grief,

I pleaded hard for just reward, and sought to find relief.

What will you more? So oft my gazing eyes did seek

To see the Rose and Lily strive upon that lively cheek[8],

Till at the last I spied and by good proof I found

That in that face was painted plain the piercer of my wound.

Then, all too late aghast, I did my foot retire,

And sought with secret sighs to quench my greedy scalding fire:

But lo, I did prevail as much to guide my will,

As he that seeks with halting heel to hop against the hill.

Or as the feeble sight would search the sunny beam[9],

Even so I found but labor lost to strive against the stream.

Then gan I thus resolve, since liking forced love,

Should I mislike my happy choice before I did it prove?

And since none other joy I had but her to see,

Should I retire my deep desire? No, no, it would not be:

Though great the duty were, that she did well deserve,

And I poor man, unworthy am so worthy a wight to serve.

Yet hope my comfort stay’d, that she would have regard

To my good will that nothing crav’d but like for just reward:

I see the falcon gent sometimes will take delight[10]

To seek the solace of her wing and dally with a kite.

The fairest wolf will choose the foulest for her make,

And why? because he doth endure most sorrow for her sake.

Even so had I like hope when doleful days were spent,

When weary words were wasted well, to open true intent.

When floods of flowing tears had wash’d my weeping eyes,

When trembling tongue had troubled her with loud lamenting cries,

At last her worthy will would pity this my plaint

And comfort me, her own poor slave, whom fear had made so faint.

Wherefore I made a vow, the stony rock should start

Ere I presume to let her slip out of my faithful heart.

L'envoy.

And when she saw by proof the pith of my good will,

She took in worth this simple song, for want of better skill.

And as my just deserts her gentle heart did move,

She was content to answer thus: I am content to love.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

7. A cloud of care hath covered all my coast

This is but a rough metre, and reason, for it was devised in great disquiet of mind and written in rage, yet have I seen much worse pass the musters, yea, and where both the Lieutenant

and Provost Marshall were men of ripe judgment[11]: and as it is I pray you let it pass

here, for the truth is that F. I. himself had so slender liking thereof, or at least

of one word escaped therein, that he never presented it -- but to the matter.

A cloud of care hath covered all my coast,

And storms of strife do threaten to appear:

The waves of woe which I mistrusted most,

Have broke the banks wherein my life lay clear:

Chips of ill chance are fallen amid my choice,

To mar the mind that meant for to rejoice.

Before I sought, I found the haven of hap,

Wherin (once found) I sought to shrowd my ship,

But lowring love hath lift me from her lap,

And crabbed lot begins to hang the lip:

The drops of dark mistrust do fall so thick,

They pierce my coat, and touch my skin at quick.

What may be said, where truth cannot prevail?

What plea may serve, where will itself is judge?

What reason rules, where right and reason fail?

Remediless then must the guiltless trudge:

And seek out care, to be the carving knife,

To cut the thread that lingereth such a life.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

See, Sir Thomas Wyatt’s translation of Petrarch, Canzoniere 189: “Passa la nave mia colma d’oblio.”

My galley charged with forgetfulness

Through sharp seas in winter nights doth pass

'Twene rock and rock; and eke mine enemy, alas

That is my lord, steerth with cruelness

And every oar a thought in readiness

As though that death were light in such a case;

An endless wind doth tear the sail apace

Of forced sighs and trusty fearfulness

A rain of tears, a cloud of dark disdain

Hath done the wearied cords great hindrance

Wreathed with error and eke with ignorance.

The stars be hid that led me to this pain,

Drowned is reason that should me comfort,

And I remain despairing of the port.

(Tottel’s Miscellany, Songes and sonettes, 1557, 2.14)

8. Dame Cinthia herself that shines so bright

This Ballad, or howsoever I shall term it, percase you will not like,

and yet in my judgment it hath great good store of deep invention,

and for the order of the verse, it is not

common, I have not heard many of like proportion.

Dame Cynthia herself (that shines so bright

And deigneth not to leave her lofty place

But only then when Phoebus shows his face,

Which is her brother born and lends her light)

Disdain'd not yet to do my Lady right,

To prove that in such heavenly wights as she,

It sitteth best that right and reason be.

For when she spied my Lady’s golden rays,

Into the clouds

Her head she shrouds

And shamed to shine where she her beams displays.

Good reason yet that to my simple skill,

I should the name of Cynthia adore,

By whose high help I might behold the more

My Lady's lovely looks at mine own will,

With deep content to gaze, and gaze my fill:

Of courtesy and not of dark disdain,

Dame Cynthia disclos'd my Lady plain.

She did but lend her light (as for a light)

With friendly grace

To show her face

That else would show and shine in her despite.

Dan Phoebus he with many a low'ring look,

Had her beheld of yore in angry wise:

And when he could none other mean devise

To stain her name, this deep deceit he took

To be the bait that best might hide his hook:

Into her eyes his parching beams he cast,

To scorch their skins that gaz'd on her full fast:

Whereby when many a man was sunburnt so,

They thought my Queen

The sun had been,

With scalding flames which wrought them all that woe[12].

And thus when many a look had lookt so long,

As that their eyes were dim and dazzled both,

Some fainting hearts that were both lewd and loath

To look again from whence the error sprong,

Gan close their eye for fear of further wrong:

And some again once drawn into the maze,

Gan lewdly blame the beams of beauty’s blaze:

But I with deep foresight did soon espy

How Phoebus meant

By false intent

To slander so her name with cruelty.

Wherefore at better leisure thought I best

To try the treason of his treachery:

And to exalt my Lady’s dignity

When Phoebus fled and drew him down to rest

Amid the waves that walter in the west.

I gan behold this lovely Ladies face

Whereon dame nature spent her gifts of grace,

And found therein no parching heat at all,

But such bright hue

As might renew

An angel's joys in reign celestial.

The courteous moon that wish’d to do me good

Did shine to show my dame more perfectly,

But when she saw her passing jollity,

The moon for shame did blush as red as blood

And shrunk aside and kept her horns in hood:

So that now when Dame Cynthia was gone,

I might enjoy my Lady’s looks alone,

Yet honored still the Moon with true intent:

Who taught us skill

To work our will

And gave us place till all the night was spent.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

The name Cynthia was given affectionately to Queen Elizabeth by her contemporaries. (See, Nos. 48 and 101.) “Mistress Ellinor”, to whom Master F.I. has dedicated this poem outshines Cynthia. In view of the fact that Mistress Ellinor is a twin sister of Elizabeth, this is no surprise.

9. That self same day, and of that day that hour

After he grew more bold & better acquainted with his Mistress’ disposition,

he adventured one Friday in the morning to go unto her chamber, and thereupon wrote as

followeth, which he termed A Friday's Breakfast.

That self same day, and of that day that hour,

When she doth reign that mocks Vulcan the smith[13],

And thought it meet to harbour in her bower,

Some galant guest for her to dally with,

That blessed hour, that bliss and happy day,

I thought it meet, with hasty steps to go

Unto the lodge, wherin my Lady lay,

To laugh for joy, or else to weep for woe.

And lo, my Lady of her wonted grace,

First lent hir lips to me (as for a kiss)

And after that her body to embrace,

Wherein dame nature wrought nothing amiss.

What followed next, guess you that know the trade,

For in this sort, my Fridays feast I made.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

Mistress Ellinor commits adultery with Master F. I., THE FORTUNATE-UNHAPPY (See, William Shakespeare, Twelft Night, II/5.)

10. Beauty shut up thy shop

And surely I have heard F. I. affirm in sad earnest that he did not only love her, but was furthermore so ravished in ecstasies with continual remembrance of his delights that he made an idol of her in his inward conceit. So seemeth it by this challenge to beauty, which he wrote in her praise and upon her name.

Beauty shut up thy shop, and truss up all thy trash,

My Nell hath stolen thy finest stuff and left thee in the lash.

Thy market now is made, thy gains are gone god wot,

Thou hast no ware, that may compare with this that I have got.

As for thy painted pale and wrinkles surfled up:

Are dear enough, for such as lust, to drink of every cup:

Thy bodies bolster’d out with bombast and with bags,

Thy rowels, thy ruffs, thy cauls, thy coifs, thy jerkins and thy jags.

Thy curling and thy cost, thy frizzling and thy fare[14],

To court, to court with all those toys, and there set forth such ware

Before their hungry eyes, that gaze on every guest,

And choose the cheapest chaffer still, to please their fancy best.

But I whose steadfast eyes could never cast a glance,

With wandring look, amid the press, to take my choice by chance,

Have won by due desert a piece that hath no peer,

And left the rest as refuse all to serve the market there:

There let him choose that list, there catch the best who can:

A painted blazing bait may serve to choke a gazing man.

But I have slipt thy flower that freshest is of hue:

I have thy corn, go sell thy chaff, I list to seek no new:

The windows of mine eyes are glaz'd with such delight[15],

As each new face seems full of faults, that blazeth in my sight:

And not without just cause I can compare her so,

Lo here my glove, I challenge him that can, or dare say no.

Let Theseus come with club, or Paris brag with brand[16],

To prove how fair their Helen was, that scourg'd the Grecian land:

Let mighty Mars himself come armed to the field:

And vaunt Dame Venus to defend, with helmet, spear and shield.

This hand that had good hap, my Helen to embrace,

Shall have like luck to foil her foes, and daunt them with disgrace.

And cause them to confess by verdict and by oath,

How far her lovely looks do stain the beauties of them both.

And that my Helen is more fair than Paris’ wife,

And doth deserve more famous praise, than Venus for her life.

Which if I not perform, my life then let me leese,

Or else be bound in chains of change, to beg for beauty’s fees.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

The poetic Earl delivers an amazing example of his skill with the otherwise awkward and clumsy “poulter’s measure” that he inherited from Surrey and Wyatt, given further meaning by its obvious similarities with Shake-speare’s: “The windows of mine eyes are glaz'd with such delight.”

11. The stately dames of Rome their pearls did wear

Of this Sonnet, I am assured that it is but a translation, for I myself have seen the invention of an

Italian, and Master I. hath a little dilated the same, but not much besides

the sense of the first, and the addition very aptly applied:

wherefore I cannot condemn his doing therein.

The stately dames of Rome their pearls did wear

About their necks to beautify their name,

But she (whom I do serve) her pearls doth bear

Close in her mouth, and smiling shows the same.

No wonder then, though ev'ry word she speaks

A jewel seems in judgment of the wise,

Since that her sug'red tongue the passage breaks

Between two rocks bedeckt with pearls of price.

Her hair of gold, her front of ivory,

A bloody heart within so white a breast,

Her teeth of pearl, lips ruby, crystal eye,

Needs must I honour her above the rest,

Since she is forméd of none other mould

But ruby, crystal, ivory, pearl, and gold.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

The poem is strongly influenced by Petrarch’s sonnet 157 (“Quel sempre acerbo et honorato giorno”):

Her locks were gold, her cheeks were breathing snow,

Her brows with ebon arch'd—bright stars her eyes,

Wherein Love nestled, thence his dart to aim:

Her teeth were pearls—the rose's softest glow

Dwelt on that mouth, whence woke to speech grief's sighs

Her tears were crystal—and her breath was flame.

(Transl. by Wollaston)

At the same time, Oxford makes an ironic reference to the arsenal of Petrarchan topoi in the poems of Bembo, Serafino l'Aquilano, Mellin de Saint-Gelais, Du Bella,yDe Magny etc. - William Shakespeare makes fun of these poetical devices in sonnet No.130: “My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun, / Coral is far more red, than her lips red...”

12. As some men say there is a kind of seed

This Sonnet treateth of a strange seed, but it tasteth most of rye, which is more common amongst men nowadays. Well, let it pass amongst the rest, & he that liketh it not, turn

over the leaf to another; I doubt not but in this register he may find some

to content him, unless he be too curious.

As some men say there is a kind of seed

Will grow to horns if it be sowed thick:

Wherwith I thought to try if I could breed

A brood of buds, well sharped on the prick:

And by good proof of learned skill I found,

(As on some speciall soil all seeds best frame)

So jealous brains do breed the battle ground,

That best of all might serve to bear the same.

Then sought I forth to find such supple soil,

And called to mind thy husband had a brain,

So that percase by travail and by toil,

His fruitful front might turn my seed to gain:

And as I groped in that ground to sow it,

Start up a horn, thy husband could not blow it.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

Master F. I. seduces Mistress Ellinor and he finds the fact that she is married more a reason for bragging than for shame. See, No. 9. - This poem was not included in the 1575 version of The Posies. - See, William Shakespeare, “The Forrester’s Song” in As You Like It (IV/2):

Take thou no scorn to wear the horn,

It was a crest ere thou wast born …

13. What state to man so sweet and pleasant were

This is the translation of Ariosto his 31th song, all but the last staff, which

seemeth as an allegory applied to the rest. It will please none

but learned ears, he was tied to the invention,

troubled in mind &c.

What state to man so sweet and pleasant were,

As to be tied in links of worthy love?

What life so bliss'd and happy might appear

As for to serve Cupid, that God above?

If that our minds were not sometimes infect

With dread, with fear, with care, with cold suspect,

With deep despair, with furious frenzy,

Handmaids to her whom we call jealousy.

For ev'ry other sop of sour chance

Which lovers taste amid their sweet delight

Increaseth joy and doth their love advance,

In pleasures place to have more perfect plight.

The thirsty mouth thinks water hath good taste,

The hungry jaws are pleas'd with each repast:

Who hath not prov'd what dearth by wars doth grow

Cannot of peace the pleasant plenties know.

And though with eye we see not ev'ry joy,

Yet may the mind full well support the same.

An absent life long led in great annoy

When presence comes doth turn from grief to game.

To serve without reward is thought great pain,

But if despair do not therewith remain,

It may be borne, for right rewards at last

Follow true service though they come not fast.

Disdains, repulses, finally each ill,

Each smart, each pain, of love each bitter taste,

To think on them gan frame the lovers will

To like each joy, the more that comes at last:

But this infernal plague, if once it touch

Or venom once the lovers mind with grouch,

All feasts and joys that afterwards befall,

The lover counts them light or nought at all.

This is that sore, this is that poisoned wound,

The which to heal nor salve nor ointments serve,

Nor charm of words, nor Image can be found,

Nor observance of stars can it preserve,

Nor all the art of Magic can prevail,

Which Zoroastes found for our avail.

Oh, cruel plague, above all sorrows smart,

With desperate death thou slay'st the lover's heart.

And me, even now, thy gall hath so infect

As all the joys which ever lover found

And all good haps that ever Troilus' sect

Achieved yet above the luckless ground:

Can never sweeten once my mouth with mell,

Nor bring my thoughts again in rest to dwell.

Of thy mad moods, and of naught else I think,

In such like seas fair Bradamant did sink.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

The first five stanzas are translated from Ariosto, Orlando Furioso, Canto XXXI (“Che dolce più, che più giocondo stato / saria di quel d'un amoroso core?”)

14. I could not though I would: good Lady say not so

F. I. compiled in verse this answer following, upon these words contained

in her letter, I could not though I would.

I could not though I would: Good Lady, say not so,

Since one good word of your good will might soon redress my woe.

Where would is free before, there could can never fail:

For proof, you see how galleys pass where ships can bear no sail.

The weary mariner when skies are overcast

By ready will doth guide his skill and wins the haven at last.

The pretty bird that sings with prick against her breast[17]

Doth make a virtue of her need: to watch when others rest.

And true the proverb is, which you have laid apart,

There is no hap can seem too hard unto a willing heart.

Then, lovely Lady mine, you say not as you should,

In doubtful terms to answer thus: I could not though I would.

Yes, yes, full well you know your can is quick and good,

And willful will is eke too swift to shed my guiltless blood.

But if good will were bent as press'd as power is,

Such will would quickly find the skill to mend that is amiss.

Wherefore if you desire to see my true love spilt,

Command and I will slay myself, that yours may be the guilt.

But if you have no power to say your servant nay,

Write thus: I may not as I would, yet must I as I may.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

15. With her in arms that had my heart in hold

This Sonnet declareth that he began now to account of her as she deserved, for

it hath a sharp conclusion, and it is somewhat too general.

With her in arms that had my heart in hold,

I stood of late to plead for pity so.

And as I did her lovely looks behold,

She cast a glance upon my rival foe.

His fleering face provoked her to smile

When my salt tears were drowned in disdain:

He glad, I sad, he laugh'd; alas the while,

I wept for woe, I pin'd for deadly pain.

And when I saw none other boot prevail

But reason's rule must guide my skilful mind:

Why then, quoth I, old proverbs never fail,

For yet was never good cat out of kind:

Nor woman true, but even as stories tell,

Won with an egg, and lost again with shell[18].

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

16. And if I did what then?

And when he was in place solitary, he compiled these

following for a final end of the matter.

And if I did what then?

Are you agrieved therefore?

The sea hath fish for every man,

And what would you have more?

Thus did my Mistress once,

Amaze my mind with doubt:

And popped a question for the nonce,

To beat my brains about.

Whereto I thus replied,

Each fisherman can wish,

That all the seas at every tide

Were his alone to fish.

And so did I (in vain),

But since it may not be:

Let such fish there as find the gain,

And leave the loss for me.

And with such luck and loss[19],

I will content myself:

Till tides of turning time may toss,

Such fishers on the shelf.

And when they stick on sands,

That every man may see:

Then will I laugh and clap my hands,

As they do now at me.

F. I.

Source: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. III, The Adventures of Master F. I., 1573

DIVERS EXCELLENT DEVISES OF SUNDRY GENTLEMEN (1573)

The Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen in the anthology A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (1573), correspond to the novella The Adventures of Master F.I. (Flowres III). Poems are used in the novella like prisms that both break up, and clarify the story. In Divers excellent Devices the poems form a lose chain of short, epic dramas, in their own right; whereby prose is merely used to guide the reader from one poem to the next.

17. When worthy Bradamant had looked long in vain

Ariosto allegorised.

When worthy Bradamant had looked long in vain,

To see hir absent love and Lord, Ruggier, return again:

Upon her loathed bed her lustless limbs did cast,

And in deceitful dreams she thought, she saw him come at last.

But when with open arms, she ran him to embrace,

With open eyes she found it false, and thus complain’d her case.

That which me pleased (quod she) was dreams which fancy drew,

But that what me torments (alas) by sight I find it true.

My joy was but a dream, and soon did fade away,

But my tormenting cruel cares cannot so soon decay.

Why hear I not and see, since now I have my senses?

That which in feigned fading dreams appeared by pretences[20].

Or whereto serve mine eyes, if sights they so mistake,

As seem to see each joy in sleep, and woe when they awake.

The sweet and slumbering sleep did promise joy and peace,

But these unpleasant sights do raise such wars as never cease.

The sleep I felt was false, and seem’d to ease my grief,

But that I see, is all too true, and yields me no relief.

If truth annoy me then, and feigned fancies please me,

God grant I never hear nor see true thing for to disease me.

If sleeping yield me joy, and waking work me woe,

God grant I sleep, and never wake, to ease my torment so.

O happy slumbering souls, whom one dead drowsy sleep

Six months (of year) in silence shut, with closed eyes did keep.

Yet can I not compare such sleep to be like death,

Nor yet such waking, as I wake, to be like vital breath.

For why my lot doth fall, contrary to the rest,

I deem it death when I awake, and life while I do rest.

Yet if such sleep be like to death in any wise,

O gentle death come quick at call, and close my dreary eyes.

Thus said the worthy dame, whereby I gather this,

No care can be compared to that, where true love parted is.

L’envoy.

Lo Lady if you had but half like care for me,

That worthy Bradamant had then her own Ruggier to see:

My ready will should be so pressed to come at call,

You should have no such sight or dream to trouble you withall.

Then when you list command, and I will come in haste,

There is no hap shall hold me back, good will shall run so fast.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

Oxford sets Ariost’s poem about the illusion of the joys of love as the leitmotif of his own poems. “When worthy Bradamant had looked long in vain” is the free tranlation of Orlando furioso, Canto XXXIII, stanzas 61-64. (“Fuggesi in questo il sonno, né veduto / è più Ruggier che se ne va con esso” etc.) - Compare to Philippe Desportes, Imitation de l’Arioste au Chant XXXIII (1572) : “Las! ce qui m’a tant pleu n’étoit rien qu’un faux songe”.

Once more Oxford makes use of the “ poulter’s metre” (See, Oxford’s Poems, No. 3), in which the alexandriner of six metrical feet alternates with the heptameter of seven feet. In doing this the poet is emulating one of his favourite poets; Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516-1547).

18. The hateful man that heapeth in his mind

Written upon a reconciliation between two friends.

The hateful man that heapeth in his mind,

Cruel revenge of wrongs forepast and done,

May not (with ease) ye pleasant pathway find,

Of friendly verse which I have now begun,

Unless at first his angry breast untwined

The crooked knot which cankered choler knit,

And then recoil with reconciled grace.

Likewise I find it said in holy writ,

If thou intend to turn thy fearful face,

To God above: make thine agreement yet,

First with thy brother whom thou didst abuse,

Confess thy faults, thy frowardness and all,

So that the Lord thy prayer not refuse.

When I consider this, and then the brawl,

Which raging youth (I will not me excuse)

Did whilom breed in mine unmellowed brain,

I thought it meet before I did assay,

To write in rhyme the double golden gain,

Of amity: first yet to take away

The grudge of grief, as thou doest me constrain,

By due desert whereto I now must yield,

And drown for aye in depth of Lethes lake,

Disdainful moods from friendship cannot wield:

Pleading for peace which for my part I make

Of former strife, and henceforth let us write

The pleasant fruits of faithful friend’s delight.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

A daring experiment in poetic form with four groups of five lines (a/b/a/b/a), one group of four lines and one group of two lines.

19. This vain avail which thou by Mars hast won

Two gentlemen did run three courses at the ring for one kiss, to be taken of a fair gentlewoman being then present, with this condition, that the winner should have the kiss, and the loser be bound to write some verses upon the gain or loss thereof. Now it fortuned that the winner triumphed, saying, he much lamented that in youth he had not seen the wars. Whereupon the loser compiled these following, in discharge of the condition above rehearsed.

This vain avail which thou by Mars hast won,

Should not allure thy flitting mind to field,

Where sturdy steeds in depth of dangers run,

By guts well gnawn by claps that canons yield.

Where faithless friends by warfare waxen wear,

And run to him that giveth best reward:

No fear of laws can cause them for to care,

But rob and reave, and steal without regard

The father’s coat, the brother’s steed from stall:

The dear friend’s purse shall picked be for pence,

The native soil, the parentes left and all,

With Tant tra tant the camp is marching hence.

But when bare beggary bids them to beware,

And late repentance rules them to retire,

Like hiveless bees they wander here and there,

And hang on them who (erst) did dread their ire.

This cut throat life (me seems) thou shouldst not like,

And shun the happy heaven of mean estate:

High Jove (perdie) may send what thou doest seek[21],

And heap up pounds within thy quiet gate.

Nor yet I would that thou shouldst spend thy days

In idleness to tear a golden time:

Like country louts which count none other praise,

But grease a sheep, and learn to serve the swine.

In vain were then the gifts which nature lent,

If Pan so press to pass Dame Pallas’ lore:

But my good friend, let thus thy youth be spent,

Serve God thy Lord, and praise him evermore.

Search out the skill which learned books do teach,

And serve in field when shadows make thee sure:

Hold with the head, and row not past thy reach,

But plead for peace which plenty may procure.

And (for my life) if thou canst run this race,

Thy bags of coin will multiply apace.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

20. The feeble thread which Lachesis hath spun

Not long after the writing hereof: he departed from the company of his said

friend (whom he entirely loved) into the west of England, and feeling himself so

consumed by women’s craft that he doubted of a safe return: wrote before

his departure as followeth.

The feeble thread which Lachesis hath spun[22],

To draw my days in short abode with thee,

Hath wrought a web which now (well-near) is done,

The wale is worn[23]: and (all to late) I see

That lingering life doth dally but in vain,

For Atropos will cut the twist in twain.

I not discern what life but loathsome were,

When faithful friends are kept in twain by want:

Nor yet perceive what pleasure doth appear

To deep desires where good success is scant.

Such spite yet shows Dame Fortune (if she frown)

The haughty hearts in high mishaps to drown.

Hot be the flames which boil in friendly minds,

Cruel the care and dreadful is the doom:

Slipper the knot which tract of time untwindes,

Hateful the life and welcome were the tomb.

Blessed were the day which might devour such youth,

And cursed the want that seeks to choke such truth.

This wailing verse I bath in flowing tears,

And would my life might end with these my lines:

Yet strive I not to force into thine ears

Such feigned plaints as fickle faith resigns.

But high foresight in dreams hath stopped my breath,

And caused the swan to sing before his death.

For lo these naked walls do well declare

My latest leave of thee I taken have:

And unknown coasts which I must seek with care

Do well divine that there shall be my grave:

There shall my death make many for to moan,

Scarce known to them, well known to thee alone.

This boun of thee (as last request) I crave,

When true report shall sound my death with fame:

Vouchsafe yet then to go unto my grave,

And there first write my birth and then my name:

And how my life was shortened many years

By women’s wiles as to the world appears.

And in reward of grant to this request,

Permit, O God, my tongue these words, to tell

(Whenas his pen shall write upon my chest)[24]

With shrieking voice mine own dear friend farewell.

No care on earth did seem so much to me,

As when my corpse was forced to part from thee[25].

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

Stylistic similarities to Surrey's “If care do cause men cry” (Tottel’s Miscellany, Songes and sonettes, 1557, 5.4), together with biographical references lead us to the assumption that young Oxford is narrating from the perspective of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516-1547). In his youth Surrey was befriended with Henry Fitzroy, Earl of Richmond (1519-1536), the illegitimate son of Henry VIII. Surrey and Fitzroy grew up together in Windsor Castle.

21. A hundreth suns (in course but not in kind)

He wrote to the same friend from Exeter, this Sonnet following.

A hundreth suns (in course but not in kind)

Can witness well that I possess no joy:

The fear of death which fretteth in my mind

Consumes my heart with dread of dark annoy.

And for each sun a thousand broken sleeps

Divide my dreams with fresh recourse of cares:

The youngest sister sharp her shear she keeps,

To cut my thread, and thus my life it wears.

Yet let such days, such thousand restless nights,

Spit forth their spite, let fates eke show their force:

Death’s daunting dart where so his buffet lights,

Shall shape no change within my friendly course:

But dead or live, in heaven, in earth, in hell

I will be thine where so my carcass dwell[26].

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

The young “Earl of Surrey”, according to the presentation of the situation, writes from Exeter, just before he sets off for France to his friend, Henry Fitzroy. Actually Surrey and Fitzroy spent the time between October 1532 and September 1533 in France, together. The use of the sonnet form (here and in the next two poems) is also reminiscent of the poetical style of the Earl of Surrey, the man who introduced the sonnet to England.

22. Not stately Troy though Priam yet did live

He wrote to the same friend from Fontaine Belle eau in France, this Sonnet in commendation of the said house of Fontaine Belle eau.

Not stately Troy though Priam yet did live,

Could now compare Fontaine Belle eau to pass:

Nor Syrian towers, whose lofty steps did strive

To climb the throne where angry Saturn was,

For outward show the ports are of such price,

As scorn the cost which Caesar spilt in Rome:

Such works within as stain the rare devise,

Which whilom he, Appelles[27], wrought on tomb.

Swift Tiber flood which fed the Roman pools,

Puddle to this where crystal melts in streams.

The pleasant place where Muses kept their schools[28]

(Not parched with Phoebe, nor banished from his beams)

Yield to those Dames, nor sight, nor fruit, nor smell,

Which may be thought these gardens to excel.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

Surrey and Fitzroy spent their year in France in the court of King François Premier in his palace at Fontainebleau. During their stay they became enamored with the new Renaissance style which King François had imported from Italy. Shortly after their return to England (1533), Fitzroy married Surrey’s sister, Mary Howard, and the Earl of Surrey married Oxford’s aunt Francis de Vere (1516-1577).

23. Lady receive, receive in gracious wise

He wrote unto a Scottish Dame whom he chose for his Mistress in the French Court,

as followeth.

Lady receive, receive in gracious wise,

This ragged verse, these rude ill scribbled lines:

Too base an object for your heavenly eyes,

For he that writes, his freedom (lo) resigns

Into your hands: and freely yields as thrall

His sturdy neck (erst subject to no yoke)

But bending now, and headlong press to fall,

Before your feet, such force hath beauty’s stroke.

Since then mine eyes (which scorn’d our English dames)

In foreign courts have chosen you for fair,

Let be this verse true token of my flames,

And do not drench your own in deep despair.

Only I crave (as I nill change for new)

That you vouchsafe to think your servant true.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

A poetical fiction based on the person of the young Earl of Surrey.

24. I cannot wish thy grief, although thou work my woe

Written to a gentlewoman who had refused him and chosen a husband (as he thought) much inferior to himself, both in knowledge, birth, and personage, wherin he bewrayeth both their names in clouds, and how she was won from him with sweet gloves and broken rings.

I cannot wish thy grief, although thou work my woe,

Since I profess to be thy friend, I cannot be thy foe:

But if things done and past might well be called again,

Then would I wish the wasted words which I have spent in vain,

Were yet untold to thee, in earnest or in game,

And that my doubtful musing mind had never thought the same.

For whiles I thee beheld, in careful thoughts I spent

My liking lust, my luckless love which ever truly meant.

And whiles I sought a mean, by pity to procure,

Too late I found that gorged hawks do not esteem the lure.

This vantage hast thou then, thou mayst well brag and boast.

Thou mightst have had a lusty lad of stature with the most,

And eke of noble mind: his virtues nothing base,

Do well declare that he descends, of ancient worthy race.

Save that I known’t his name, and though I could it tell,

My friendly pen shall let it pass, because I love him well.

And thou hast chosen one of meaner parentage,

Of stature small and therewithal, unequal for thine age.

His thews unlike the first, yet hast thou hot desire

To play thee in his flitting flames, God grant they prove not fire.

Him holdest thou as dear, and he thy Lord shall be,

(Too late alas) thou lovest him, that never loved thee.

And for just proof hereof, mark what I tell is true,

Some dismal day shall change his mind, and make him seek a new.

Then wilt thou much repent, thy bargain made in haste,

And much lament those perfumed gloves which yield such sour taste;

And eke the falsed faith which lurks in broken rings,

Though hand in hand say otherwise, yet do I know such things.

Then shalt thou sing and say, farewell my trusty squire,

Would God my mind had yielded once unto thy just desire.

Thus shalt thou wail my want, and I thy great unrest,

Which cruel Cupid kindled hath within thy broken breast.

Thus shalt thou find it grief which erst thou thoughtest game,

And I shall hear the weary news, by true reporting fame:

Lamenting thy mishap, in source of swelling tears,

Hardning my heart with cruel care which frozen fancy bears.

And though my just desert thy pity could not move,

Yet will I wash in wailing words, thy careless childish love.

And say as Troilus said, since that I can no more [29],

Thy wanton will did waver once, and woe is me therefore.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

25. If men may credit give to true reported fames

In praise of a gentlewoman who though she were not very fair,

yet was she as hard favoured as might be.

If men may credit give, to true reported fames,

Who doubts but stately Rome had store of lusty, loving dames?

Whose ears have been so deaf, as never yet heard tell,

How far the fresh Pompeïa for beauty did excel.

And golden Marcus he, that swayed the Roman sword,

Bare witness of Boemia[30], by credit of his word.

What need I mo rehearse? since all the world did know,

How high the floods of beauty’s blaze within those walls did flow.

And yet in all that choice a worthy Roman knight,

Antonius who conqueréd proud Egypt by his might,

Not all to please his eye, but most to ease his mind,

Chose Cleopátra for his love[31], and left the rest behind.

A wondrous thing to read, in all his victory,

He snapt but her for his own share, to please his fantasy.

She was not fair, God wot, the country breeds none bright,

Well may we judge her skin the foil, because her teeth were white.

Percase her lovely looks some praises did deserve,

But brown, I dare be bold, she was, for so the sol did serve.

And could Antonius forsake the fair in Rome?

To love his nutbrown Lady best[32], was this an equal doom?

I dare well say, dames there did bear him deadly grudge,

His sentence had been shortly said, if Faustine had been judge[33].

For this I dare avow, (without vaunt be it spoke)

So brave a knight as Anthony, held all their necks in yoke:

I leave not Lucrece out, believe in her who list,

I think she would have lik'd his lure, and stooped to his fist.

What mov'd the chieftain then, to link his liking thus?

I would some Roman dame were here, the question to discuss.

But I that read her life, do find therein by fame,

How clear her courtesy did shine, in honour of her name.

Her bounty did excel, her truth had never peer,

Her lovely looks, her pleasant speech, her lusty, loving cheer.

And all the worthy gifts, that ever yet were found,

Within this good Egyptian Queen, did seem for to abound.

Wherefore he worthy was, to win the golden fleece,

Which scored the blazing stars in Rome, to conquer such a piece.

And she to quite his love, in spite of dreadful death,

Enshrined with snakes within his tomb, did yield her parting breath.

Allegoria.

If fortune favour’d him, then may that man rejoice,

And think himself a happy man by hap of happy choice.

Who loves and is belov'd of one as good, as true,

As kind as Cleopátra was, and yet more bright of hue.

Her eyes as grey as glass, her teeth as white as milk,

A ruddy lip, a dimpled chin, a skin as smooth as silk.

A wight what could you more, that may content man’s mind,

And hath supplies for ev'ry want, that any man can find.

And may himself assure, when hence his life shall pass,

She will be stong to death with snakes, as Cleopátra was.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

26. Were my heart set on high

He began to write by a gentlewoman who passed by him with her arms set bragging

by her sides, and left it unfinished as followeth.

Were my heart set on high as thine is bent,

Or in my breast so brave and stout a will:

Then (long ere this) I could have been content,

With sharp revenge thy careless corpse to kill.

For why thou knowst (although thou know not all)

What rule, what reign, what power, what seigniory,

Thy melting mind did yield to me (as thrall)

When first I pleased thy wandring fantasy.

What lingering looks bewray'd thine inward thought,

What pangs were published by perplexity,

Such wreaks the rage of love in thee had wrought

And no gramercy for thy courtesy[34].

I list not vaunt, but yet I dare avow

(Had been my harmless heart as hard as thine)

I could have bound thee then for starving now,

In bonds of bale, in pangs of deadly pine.

For why by proof the field is eath to win,

Where as the chieftains yield themselves in chains:

The port or passage plain to enter in

Where porters list to leave the key for gains[35].

But did I then devise with cruelty,

(As tyrants do) to kill the yielding prey?

Or did I brag and boast triumphantly,

As who should say the field were mine that day?

Did I retire myself out of thy sight

To beat afresh the bulwarks of thy breast?

Or did my mind in choice of change delight,

And render thee as refused with the rest?

No tiger no, the lion is not lewd,

He shows no force on seely wounded sheep,

etc.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

In the poems Nos. 26 through 28 the common factor is that of love which turns to hatred and contempt. (A theme that we often see in Oxford’s works.)

27. How long she looked that looked at me of late

Whiles he sat at the door of his lodging, devising these verses above rehearsed, the same Gentlewoman passed by again and cast a long look towards him, whereby he left his former invention and wrote thus.

How long she looked that looked at me of late,

As who would say, her looks were all for love:

When God he knows they came from deadly hate,

To pinch me yet with pangs which I must prove.

But since my looks her liking may not move,

Look where she likes, for lo this look was cast,

Not for my love, but even to see my last.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

28. I looked of late and saw thee look askance

Another Sonnet written to the same Gentlewoman, upon the same occasion.

I looked of late and saw thee look askance,

Upon my door, to see if I sat there.

As who should say: If he be there by chance,

Yet may he think I look him everywhere.

No cruel, no, thou knowst and I can tell,

How for thy love I laid my looks aside:

Though thou (percase) hast looked and liked well,

Some new found looks amid this world so wide.

But since thy looks my love have so enchained

That in my looks thy liking now is past:

Look where thou likest, and let thy hands be stained

In true love’s blood which thou shalt lack at last.

So look, so lack, for in these toys thus tossed,

My looks thy love, thy looks my life have lost.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

29. The thriftless thread which pamper’d beauty spins

Enough of this Dame. And let us peruse his other doings which have come to my hands, in such disordred order, as I can best set them down. I will now then present you with a

Sonnet written in praise of the brown beauty which he compiled for

the love of Mistress E. P. as followeth.

The thriftless thread which pamper’d beauty spins,

In thralldom binds the foolish gazing eyes:

As cruel spiders with their crafty gins,

In worthless webs do snare the simple flies.

The garments gay, the glittring golden gite,

The ticing talk which flows from Pallas’ pools:

The painted pale, the (too much) red made white,

Are smiling baits to fish for loving fools[36].

But lo, when eld in toothless mouth appears,

And hoary hairs instead of beauties blaze:

Then Had I wist doth teach repenting years,

The tickle track of crafty Cupid’s maze.

Twixt fair and foul therefore, twixt great and small,

A lovely nutbrown face is best of all[37].

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

30. When danger keeps the door of Lady Beauty’s bower

Written to a Gentlewoman in Court, who (when she was there placed) seemed to disdain him,

contrary to a former profession.

When danger keeps the door of Lady Beauty’s bower,

When jealous toys have chased trust out of her strongest tower:

Then faith and truth may fly, then falsehood wins the field,

Then feeble naked faultless hearts for lack of fence must yield.

And then prevails as much to hop against the hill,

As seek by suit for to appease a froward Lady’s will.

For oaths and solemn vows are wasted then in vain,

And truth is counted but a toy, when such fond fancies reign.

The sentence soon is said, when will itself is judge,

And quickly is the quarrel picked, when Ladies list to grudge.

This sing I for myself, (which wrote this weary song)

Who justly may complain my case, if ever man had wrong.

A Lady have I serv'd, a Lady have I lov'd,

A Lady’s good will once I had, her ill will late I prov'd.

In country first I knew her, in country first I caught her,

And out of country now in court, to my cost have I sought her.

In court where Princes reign, her place is now assigned,

And well were worthy for the room, if she were not unkind.

There I (in wonted wise) did show myself of late,

And found that as the soil was chang'd, so love was turned to hate.

But why? God knows, not I: save as I said before,

Pity is put from porter’s place, and danger keeps the door.

If courting then have skill to change good Ladies so,

God send each willful Dame in court some wound of my like woe.

That with a troubled head she may both turn and toss,

In restless bed when she should sleep and feel of love the loss.

And I (since porters put me from my wonted place)

And deep deceit hath wrought a wile to wrest me out of grace:

Will home again to cart, as fitter were for me,

Than thus in court to serve and starve, where such proud porters be.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

The court life leading to falsehood and deception is detrimental to the development of true love. See, No. 100: “Faction that ever dwells”. In spite of the fact that it is written in the monotonous rhythmic chant of the “poulter’s measure” (Compare to No. 3), the poem has a lively and varied character.

31. Thou with thy looks on whom I look full oft

From this I will skip to certain verses written to a Gentlewoman whom he liked very well, and yet had never any oportunity to discover his affection, being always bridled by jealous looks which attended them both, and therefore guessing by her looks, that she partly also liked him: he wrote in a book of hers as followeth.

Thou with thy looks on whom I look full oft,

And find there in great cause of deep delight:

Thy face is fair, thy skin is smooth and soft,

Thy lips are sweet, thine eyes are clear and bright,

And every part seems pleasant in my sight.

Yet wot thou well, those looks have wrought my woe,

Because I love to look upon them so.

For first those looks allured mine eye to look[38],

And straight mine eye stirred up my heart to love:

And cruel love with deep deceitful hook,

Choked up my mind whom fancy cannot move,

Nor hope relieve, nor other help behove:

But still to look, and though I look too much,

Needs must I look because I see none such.

Thus in thy looks my love and life have hold,

And with such life my death draws on apace:

And for such death no medcine can be told,

But looking still upon thy lovely face[39],

Wherin are painted pity, peace and grace,

Then though thy looks should cause me for to die,

Needs must I look, because I live thereby.

Since then thy looks my life have so in thrall,

As I can like none other looks but thine:

Lo here I yield my life, my love, and all

Into thy hands, and all things else resign,

But liberty to gaze upon thine eyne.

Which when I do, then think it were thy part,

To look again, and link with me in heart.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

With these verses you shall judge the quick capacity of the Lady: for she wrote therunder this short answer.

Look as long as you list, but surely if I take you looking,

I will look with you.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

32. I cast mine eye and saw ten eyes at once

And for a further proof of this Dame’s quick understanding, you shall now understand, that soon after this answer of hers, the same Authour chanced to be at a supper in her company, where were also her brother, her husband and an old lover of hers by whom she had been long suspected. Now, although there wanted no delicate viandes to content them, yet their chief repast was by enterglancing of looks. For G.G. being stong with hot affection, could none otherwise relieve his passion but by gazing. And the Dame of a courteous inclination deigned (now and then) to requite the same with glancing at him. Her old lover occupied his eyes with watching: and her brother perceiving all this could not abstain from winking, whereby he might put his sister in remembrance, least she should too much forget herself. But most of all her husband beholding the first, and being evil pleased with the second, scarce contented with the third, and misconstruing the fourth, was constrained to play the fifth part in froward frowning. This royal banquet thus passed over, G.G. knowing that after supper they should pass the time in propounding of riddles and making of purposes: contrived all this conceit in a riddle as followeth. The which was no sooner pronounced, but she could perfectly perceive his intent, and drove out one nail with another, as also ensueth.

His riddle.

I cast mine eye and saw ten eyes at once,

All seemly set upon one lovely face:

Two gaz'd, two glanc'd, two watched for the nonce,

Two winked wiles, two frowned with froward grace.

Thus every eye was pitched in his place.

And every eye which wrought each others woe,

Said to itself, alas why looked I so

And every eye for jealousy did pine,

And sigh'd and said, I would that eye were mine.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

The construction of poetic conundrums (which weren’t always difficult to solve) was a form of parlour game. We see it described in Baldassare Castiglione’s famous work Il Libro del Cortegiano (1528).

With the intention of misleading the reader, Oxford writes a poem, pretending to be G. G. (George Gascoigne). He only however adopts the abbreviation of Gascoigne’s name, not his literary characteristics. The poem is clearly written in Oxford’s style. - The strategy of adopting different names was part of a game of hide and seek that Oxford played with his readers. (See, 5.0 Introduction.)

33. What thing is that which swims in bliss

In all this lovely company was not one that could and would expound the meaning hereof. At last the Dame herself answered on this wise. Sir, quod she, because your dark speech is much too curious for this simple company, I will be so bold as to quit one question with another. And when you have answered mine, it may fall out peradventure, that I shall somewhat the better judge of yours.

Her Question.

What thing is that which swims in bliss,

And yet consumes in burning grief:

Which being placed where pleasure is,

Can yet recover no relief.

Which sees to sigh, and sighs to see,

All this is one, what may it be?

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

The solution to the riddle: The kiss. - See, No. 58: “A Lady once did ask of me”.

34. I groped in thy pocket, pretty peat

He held himself herewith contented: and afterwards when they were better acquainted, he chanced once (groping in her pocket) to find a letter of her old lover’s: and thinking it were better to wink than utterly to put out his eyes, seemed not to understand this first offence: but soon after finding a lemon (the which he thought he saw her old leman put there) he devised thereof thus, and delivered it unto her in writing.

I groped in thy pocket, pretty peat,

And found a leman which I looked not:

So found I once (which now I must repeat)

Both leaves and letters which I liked not.

Such hap have I to find and seek it not,

But since I see no faster means to bind them

I will (henceforth) take lemans as I find them.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

Word play on leman (sweetheart, unlawful lover) and lemon. - See, W. Shakespeare: „I sent thee sixpence for thy lemon: hadst it?“ (Twelfth Night, II/3).

35. A lemon (but no leman) Sir you found

The Dame within very short space did answer it thus.

A lemon (but no leman) Sir you found,

For lemans bear their name to broad before:

The which since it hath given you such a wound,

That you seem now offended very sore:

Content yourself you shall find (there) no more.

But take your lemans henceforth where you lust,

For I will show my letters where I trust.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

36. When steadfast friendship (bound by holy oath)

This Sonnet of his shall pass (for me) without any preface

When steadfast friendship (bound by holy oath)

Did part perforce my presence from thy sight,

In dreams I might behold how thou wert loath

With troubled thought to part from thy delight.

When Poplar walls enclosed thy pensive mind,

My painted shadow did thy woes revive:

Thine evening walks by Thames in open wind,

Did long to see my sailing boat arrive.

But when the dismal day did seek to part

From London walls thy longing mind for me,

The sugared kisses (sent to thy dear heart)

With secret smart in broken sleeps I see.

Wherefore in tears I drench a thousand fold,

Till these moist eyes thy beauty may behold.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

This poem was not included in the 1575 version of The Posies. It’s overall mood along with its tone bears a resemblance to Shakespeare’s Sonnet 27 (“Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed”). - The question is: what does the author mean by “Poplar walls”?

Poplar was situated in the parish of Stepney just east of London. “The supposition is that Poplar’s name came simply from the large number of poplar trees which in olden times, nurtured by the moist riverside soil, were to be seen here. Dr. Woodward, who seems to have been the first to call attention to this now generally accepted derivation of the name, declares that when he wrote in 1720, many of these poplars were still standing ‘as testimonials to the truth of that etymology’.” (Official Guide to the Metropolitan Borough of Poplar, 1927.)

The situation is confusing. The parish of “Poplar” (so named after the many poplar trees that grew there) was on one side of the Thames. In the midst stood an impressive mansion, once bequeathed to Sir Gilbert Dethick (c.1510-1584) by Henry VIII. – However , on the other side of the Thames was built a far more impressive dwelling; Grenwich Palace, also known as “The Manor of Pleasance.” It stood at the bottom-right of the U-shaped dip formed by the southward projection of land which included the ‘Isle of Dogs’ – and the ‘Poplar walls’.

Which side of the river does the woman live on whom Oxford serenades so passionately? At the time in question the Dethick family does not have a beautiful woman to boast of. When Queen Elizabeth looked out of the window of her castle in Greenwich, her gaze fell on the poplar trees of the parish of Poplar. Could it be that, whilst strolling of an evening, her eyes searched for a young man who sometimes moved from one river bank to another, causing him to say:

Thine evening walks by Thames in open wind,

Did long to see my sailing boat arrive.

That is not all. We are allowed to accompany the young poet when he crosses the river in his boat. In: “This tenth of March when Aries receiv’d” (No. 40) we find the words:

In pleasant garden (placed all alone)

I saw a Dame who sat in weary wise,

With scalding sighs she uttered all her moan,

The rueful tears down rained from her eyes:

Her lowering head full low on hand she laid,

On knee her arm: and thus this Lady said.

Alas (quod she) behold each pleasant green,

Will now renew his sommers livery,

The fragrant flowers which have not long been seen,

Will florish now (ere long) in bravery …

The lusty Ver which whilom might exchange

My grief to joy, and then my joy’s increase,

Springs now elsewhere and shows to me but strange...

37. Of all the birds that I do know

He wrote (at his friends request) in praise of a Gentlewoman, whose name

was Phillip, as followeth.

Of all the birds that I do know,

Phillip my sparrow hath no peer:

For sit she high or lie she low,

Be she far off, or be she near,

There is no bird so fair, so fine,

Nor yet so fresh as this of mine.

Come in a morning merrily,

When Phillip hath been lately fed,

Or in an evening soberly,

When Phillip list to go to bed:

It is a heaven to hear my Phip,

How she can chirp with cheery lip.

She never wanders far abroad,

But is at hand when I do call:

If I command she lays on load,

With lips, with teeth, with tongue and all.

She chants, she chirps, she makes such cheer,

That I believe she hath no peer.

And yet besides all this good sport,

My Phillip can both sing and dance[40]:

With new found toys of sundry sort,

My Phillip can both prick and prance:

As if you say but fend cut phip[41],

Lord how the peat will turn and skip.

Her feathers are so fresh of hue,

And so well proined every day:

She lacks none oil, I warrant you:

To trim her tail both trick and gay,

And though her mouth be somewhat wide,

Her tongue is sweet and short beside.

And for the rest I dare compare,

She is both tender, sweet and soft:

She never lacketh dainty fare,

But is well fed and feedeth oft:

For if my phip have lust to eat,

I warrant you Phip lacks no meat.

And then if that her meat be good,

And such as like do love alway:

She will lay lips theron by th’ rod [42],

And see that none be cast away:

For when she once hath felt a fit,

Phillip will cry still, yit, yit, yit.

And to tell truth he were to blame,

Which had so fine a bird as she,

To make him all this goodly game,

Without suspect or jealousy:

He were a churl and knew no good,

Would see her faint for lack of food.

Wherefore I sing and ever shall,

To praise as I have often prov'd

There is no bird amongst them all,

So worthy for to be belov'd.

Let other praise what bird they will,

Sweet Phillip shall be my bird still.

Si fortunatus infoelix.

Source. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, chapt. IV, Divers excellent Devises of sundry Gentlemen, 1573

The author is familiar with two famous poems from Catcull, Carmina 2 and 3 (Sparrow, favorite of my girl and My girl's sparrow is dead), and with the poem Phyllip Sparowe from the Poet laureate and tutor to Prince Henry (later Henry VIII) , John Skelton (c.1460-1529). - The sparrow was generally used as a symbol of wantonness. The „birds“ of Master Fortunatus Infoelix are fun-loving young girls.

38. The partridge in the pretty merlin’s foot

Now to begin with another man, take these verses written to be sent with a ring,

wherein were engraved a partridge

in a merlin’s foot.

The partridge in the pretty merlin’s foot,

Who feels her force suppressed with fearfulness,

And finds that strength nor strife can do her boot,

To scape the danger of her deep distress:

These woeful words may seem for to rehearse

Which I must write in this waymenting verse.

What helpth now (sayeth she) Dame Nature’s skill,

To dye my feathers like the dusty ground?

Or what prevails to lend me wings at will

Which in the air can make my body bound?

Since from the earth the dogs me crave perforce,

And now aloft the hawk hath caught my course.

If change of colours could not me convey,

Yet mought my wings have scaped the dogs despite:

And if my wings did fail to fly away,

Yet mought my strength resist the merlin’s might.

But nature made the merlin me to kill,

And me to yield unto the merlin’s will.

My lot is like (dear Dame) believe me well,

The quiet life which I full closely kept,

Was not content in happy state to dwell,

But forth in haste to gaze on thee it leapt.

Desire the dog did spring me up in haste,

Thou wert the hawk, whose talents caught me fast.

What should I then, seek means to fly away?

Or strive by force, to break out of thy feet?

No, no, perdie, I may no strength assay,

To strive with thee iwis, it were not meet.

Thou art that hawk whom nature made to hent me,