- To The Reader

- 1. Shakspere or Shakespeare?

- 2. Shakespeare a Pseudonym?

- 3. Treasure Texts

- 4. Edward de Vere

- 5. Works

- 6. Ben Jonsonís Forgery

- 7. Research for Shake-speare

- 9. Relationship

- 10. Chronology

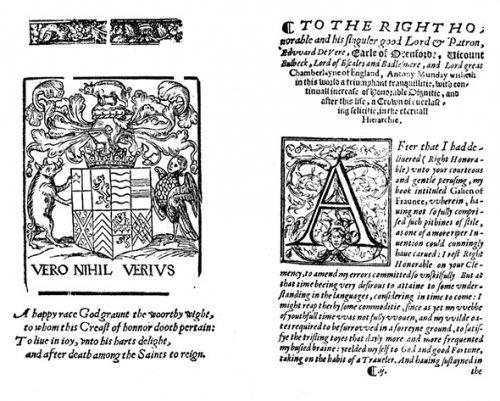

3.3.3. Munday, Mirrour of Mutabilitie, 1579

Anthony Munday was every bit as ambitious and career minded as Oxford’s secretary, John Lyly. Just like many other authors of the period, Munday supplemented his meager earnings from his literary works by taking on missions from Francis Walsingham’s secret service. Anthony Munday seems to be a very versatile man who led a double life: Born somewhere between 1553 and 1560, he earned his living as a cloth maker or perhaps a printer’s apprentice as a composer of ballads, actor, pamphleteer, translator of chivalric novels, writer of plays, masques and chronicles.

In 1578 he made Oxford a gift of the translation of Galien [Galen] of France - (presumed lost) after which he doubtlessly left for Rome on a mission for the secret service, travelling though France. On arriving in Rome he assumed the identity of a candidate for the priesthood, infiltrated a group of English Catholics and successfully spied on them. He described his methods quite candidly in the foreword to his book The Mirrour of Mutabilitie (1579) which he dedicated to his “Lord & Patron” Oxenford. In the light of the relationship between Oxford and his “Vasallo e Servitore”, anyone who speaks of the Earl’s crypto-Catholic tendencies is guilty of the falsification of history. When all said and done, Anthony Munday felt duty bound to expose the Jesuit Edmund Campion (1540-1581) and his colleagues; a denunciation which led to their execution.

In his book The Mirrour of Mutabilitie Munday delivers a discourse on the history of human vanitas. He features various biblical characters and discusses their unfortunate fates or their personal failings. His work underpins the view that Time is a destroyer, that human actions cannot be calculated positively, because life is temporal and full of accidents.

In his first publication, the flexible author paid his respects to his patron; Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. The fact that he was Oxford’s servant indicates, with a high degree of probability, that he was also a member of the acting company; “Oxford’s Men” which stood under Oxford’s patronage. In the dedication poem written in Latin, Munday lavishly praises his patron, calling him his “Alexis” with whom he would gladly share a glass of wine. (This is a reference to the Greek author of comedy and not Vergil’s Alexis.) Munday said that the Earl was able to banish his sadness- most probably by the provision of a permanent position.

The mirrour of mutabilitie, or Principall part of the Mirrour for magistrates

Describing the fall of divers famous princes, and other memorable personages.

Selected out of the sacred Scriptures by Antony Munday, and dedicated to

the Right Honourable the Earle of Oxenford.

Imprinted at London : By Iohn Allde and are to be solde by Richard Ballard, at Saint Magnus Corner, 1579.

A happy race God grant the worthy wight

To whom this crest of honour doth pertain,

To live in joy unto his heart’s delight,

And after death among the saints to reign.

To the right Honourable his singular good Lord & Patron,

Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxenforde,

Viscount Bulbeck, Lord of Escales and Badlesmere, and Lord Great Chamberlain of England, Anthony Munday wisheth in this world a triumphant tranquility with continual increase of Honourable Dignity, and after this life a Crown of everlasting felicity in the eternal Hierarchy.

After that I had delivered (Right Honourable) unto your courteous and gentle perusing my book intituled Galien of France [1], wherein having not so fully comprised such pithiness of style as one of a more riper Invention could cunningly have carved: I rest, Right Honourable, on your Clemency to amend my errors committed so unskilfully. But at that time being very desirous to attain to some understanding in the languages, considering in time to come: I might reap thereby some commodity, since as yet my web of youthful time was not fully woven and my wild oats required to be furrowed in a foreign ground, to satisfy the trifling toys that daily more and more frequented my busied brain: yielded myself to God and good Fortune, taking on the habit of a Traveller. And having sustained in the cold Country of France divers contagious calamities and sundry sorts of mishaps, as first, being but newly arrived and not acquainted with the usage of the Country, between Boulogne and Abbeville my companion and I were stripped into our shirts by Soldiers, who (if rescue had not come) would have endamaged our lives also. Methought this was but an unfriendly welcome, considering before I thought that every man beyond the Seas was as frank as an Emperor, and that a man might live there a Gentleman’s life and do nothing but walk at his pleasure, but finding it not so: I wished myself at home again, with sorrow to my sugared sops. But calling to mind that he which fainteth at the first assault would hardly endure to fight out the Battle, took Courage afresh, hoping my hap would prove better in the end since it had such a bitter beginning, and passed forward to Paris.[2]

Being there arrived, to recompense my former mishaps: I found the world well amended, for not only I obtained new garments, but divers Gentlemen to be my friends also, some that had sustained as ill fortune as I, and therefore returned back again into England, and other some that were very glad of my coming, in hope I had been such a one as they looked for.[3] But repelling such Satanical illusions, such golden proffers of preferment to advance me unto my larger contentment: I gave them the hearing of all their politic devises which (as they thought) had taken deep root at their first planting. And considering that I had enterprised this journey for my pleasure and in hope to attain to some knowledge in the French tongue, if that I should seem too scrupulous in their presence: it might turn to my farther harm. For there no friends I had to help me, no wealth to maintain me, no succour near to save me, but if I denied, my new friends would disdain: persuaded myself in their presence to do as they bade me, but when they were absent: to do then as pleased me. By these means I obtained their lawful favour, insomuch that they therewith provided me for my journey to Rome. Where for my more preferment likewise they delivered me divers letters to sundry persons (whose names I remit), that there I should be placed in the office of a Priest. Well, my friend, and I gave them a thousand thanks for their liberal expenses and friendly Letters, and so we departed.

But when we had with a night’s rest pondered of our journey, we considered the imminent dangers before our eyes. First how ready Satan stood to tempt us and prick us forward still to the eternal perdition of our souls. Secondly, that we should forsake so soon the title and name of a Christian, and yield our necks to the yoke and slavery of the Roman Decretals, in that we, professing ourselves before faithful followers of our dear Master Christ, should now so wilfully forsake him. Thirdly, unto all our friends (especially our Parents) what an heart sorrow it would be to hear how their liberal expenses bestowed on us in our youth in training us up in virtuous educations is now so lightly regarded: as able to cause the Father to yield his breath for the sorrow conceived through the negligence of his Son, and all in general lament our unnatural usages. Fourthly, from the Servants of one eternal true God to come to be Idolaters, Worshippers of stocks and stones, and so forsake the fear of God, our duty to our sovereign Prince, and our love to our parents and all affection to our friends. All these (being the principal points) thoroughly considered: withdrew my mind from my former intent, as having knowledge of my Lord the English Ambassador then lying in Paris [4], to him we went and delivered our aforesaid Letters, desiring the prudent counsel of his Honour therein. His Honour, perceiving our imbecility, and opening the Letters, found therein whereof I have before certified your Honour, which when he had worthily balanced in the breast of a second Solon, said:

My dear and faithful Countrymen (as I hope you are), not so glad of your welfare as sorry for your arrival in that you hazard yourselves on such a stayless state, to become as friends to your enemies and foes to your country, here standing at the mercy of a ravening Wolf who not only would devour you from your Country, but both body and soul from Heavenly felicity: Better therefore to abide the poverty of this your want and necessity, than to sell yourselves wilfully into such perpetual slavery, and not only to your great ignomy, but to your friends’ perpetual infamy, to your Prince and famous Country, if you leave your Captain thus cowardly. Take heart afresh courageously, and dread no calamity; take patient all adversity, and God will assist ye.[5]

The excellent Discourse pronounced by so prudent a personage methought did demonstrate the excellency of true nobility. And then departing from his Honour, I journeyed into Italy, to Rome, Naples, Venice, Padua and divers other excellent Cities. And now returned, remembering my bounden duty to your Honour, I present you with these my simple labours, desiring pardon for my bold attempt.

Faccio fine, è riverentemente baccio le vostre valorose Mani.

Humilissimo e Divotissimo e sempre Osservandissimo Vasallo e Servitore.[6]

Anthony Munday

The Author’s Commendation of the Right Honourable Earl of Oxenford

E xcept I should in friendship seem ingrate,

D enying duty whereto I am bound:

W ith letting slip your Honour’s worthy state,

A t all assays which I have Noble found,

R ight well I might refrain to handle pen:

D enouncing aye the company of men.

D own, dire despair, let courage come in place,

E xalt his fame whom Honour doth embrace.

V irtue hath aye adorned your valiant heart,

E xampled by your deeds of lasting fame:

R egarding such as take God Mars his part,

E ach-where by proof in honour and in name.

E ach one doth know no fables I express,

A s though I should encroach for private gain:

R egard you may (at pleasure), I confess,

L etting that pass, I vouch to dread no pain:

E ach-where gainst such as can my faith distain,

O r once can say, he deals with flattery:

F orging his tales to please the fantasy.

O f mine intent your Honour judge I crave,

X ephirus blow your fame to Orient skies,

E xtol, I pray, this valiant Britain brave,

N ot seeming once Bellona to despise,

F or valiantness, behold young Caesar here,

O r Hannibal, lo Hercules in place,[7]

R ing forth (I say), his fame both far and near,

D oubt not to say, de Vere will foes deface.

Verses written by the Author upon his Lord’s Posy. VERO NIHIL VERIUS.

V irtue displays the truth in every cause,

E ach vain attempt her puissance doth disprove:

R epelling falsehood, that doth seek each clause

O f dire debate Dame Truth for to remove.

N othing, we say, that truer is than truth,

I t folly is against the stream to strive:

H ard is the hap that unto such ensueth,

I n vain respects the truth for to deprive;

L et such take heed, for folly doth them drive.

V aunt not too much of thy vainglorious state,

E steem the truth, for she will guide thee right:

R efrain alway to trust to fickle fate,

I n end she fails, so simple is her might;

U se tried truth, so shalt thou never fall:

S weet is the yoke that shall abridge thy thrall.

AD PRECLARUM

et nobilissimum Virum E O. [8]

Nauta Mari medio vectus spumantibus undis,

depositis portu, sperat reperire salutem:

Conscius extremo procumbens Carcere latro

sperat fortunam lucis sentire ministram.

Pallidus attonito vultu tardatur Amator

Finem tamen dominam confidit habere benignam.

A patriis sperat Perigrinus finibus exul:

Orbe pererrato sibi conciliare quietem.

Hac ratione meum vino visurus Alexin,

Tristitiaeque meae latas perstringere fines,

Speque recreabor, medicum Fortuna resistat,

Donec opem ferat, et morbo medicator acerbo[9].

Non aliquando diem tantae peressere tenebrae,

quin redeat spargens glebis sua fulmina Phoebus.

Aequora quando metam certam posuere furendi,

Gaudia securis ego sic possessa tenebo.

Mi formose vale, valeat tua grata voluntas,

Deprecor optata tutus potiaris arena.

Te, cunctosque tuos CHRISTO committo tuendos,

Donec praestantes sermone fruamur amico.

Honos alit Artes

[Translation] To the famous and most noble man E O.

The mariner, whilst battling through the wildest seas, hopes to reach the sanctity

of the harbor when the stormy waves have ebbed.

The guilt ridden thief languishing in the darkest dungeon hopes that one day Fortuna

will send him a ray of sunshine. [10]

The pale lover, who, shunned by the stony glance of his lady, still hopes that one day

she will look kindly upon him and return his love.

The stranger who, banned from family and home, travels around the world hopes to find

peace and comfort.

I who wish to sit with my Alexis over a glass of wine,[11]

that he may banish my sadness,

am comforted by the hope that Fortuna will delay the doctor [=Alexis] long enough

to bring me the help that will cure this bitter illness.

Not even the deepest darkness can prevent the return of Phoebus

when he spreads his rays over the swell.

When the seas cease to roar,

I shall enjoy the pleasures of my office.

Farewell to you, most fair and noble Lord

[12],

a fond farewell to your benevolent spirit.

I pray that you may rule the arena [=the stage] without harm to yourself.

May our Lord Jesus Christ protect you and yours,

Until we sit face to face deepened in friendly conversation.

Art thrives on honor.

It is surprising that such assiduousness should appear out of thin air from the pen of a “servitore”. Normally, such a gushing style indicates that a young, rather naïve person is addressing a close friend or relative. We need to investigate the age of the young author and the nature of his relationship to the Earl of Oxford.

He was once thought to have been born in 1553, because the monument to him (in the church of St. Stephen Coleman Street) stated that at the time of his death he was eighty years old. His monument, with a long inscription, was destroyed in 1666, but the inscription was printed in full in the 1633 edition of John Stow's Survay of London (p. 869). However, as was demonstrated by I. A. Shapiro in an essay from 1956, the lost inscription is probably based on a mistake (see Mundy‘s Birthdate, Notes and Queries, January 1956, pp. 2-3). There are three matters which speak against 1553 being the year of his birth.

1. “William Hall wrote verses ‘in commendaton for his Kinseman Antony Munday’ of the latter’s Mirrour of Mutability, 1579. In these Hall refers to Munday’s ‘tender time to take such task in hand’, which is explicable only if Munday was then considerably less than twenty-six.

2. “At the very end of January or the beginning of February 1582, Munday, then a pursuivant actively hunting Catholics, published A Discoverie of Edmund Campion and his Confederates, describing the trials and executions of Campion, Sherwin und Brian. Munday’s hostile account immediately evoked A true reporte of the death … of M. Campion, published before the middle of march 1582. On D4v of the latter is ‘A caveat to the reader touching A. M. his discovery’ giving invaluable information about Munday’s career up to 1582. In the course of it the author informs us that Munday ‘set forth a balet [ballad] against playes, but yet (o constant youth) he now beginnes again to ruffle upon the stage … Yer I thinke it not amiss to remember thee of this Boyes infelicitie two several wayes of late notorious…’. – The author [Thomas Aufield] of this ‘Caveat’[13] was clearly well supplied with biographical data about Munday, and his references to the ‘constant youth’ and ‘this boy’ are not to be disregarded.”

3. “We must take seriously the implications of the apprenticeship entry. The Stationers’s records show that apprenticeships were carefully regulated, especially about the time Munday was bound. An apprentice was required to serve for a minimum term of seven years, or for so much longer as was necessary to make him at least twenty-four years old at the expiration of his time. Munday was bound for eight years from ‘Bartholomewtide’ (August 24) 1576; he must, then, have expected to be twenty-four years old by 24 August 1584.”

I. A. Shapiro arrives at the year of 1560 as being the correct year of his birth.

That means that Munday must have been 18 when he set off for Italy! That further means that he must have been 19 when he wrote The Mirrour of Mutabilitie, and a year later he wrote Zelauto, The Fountain of Fame (1580).

Munday’s youth explains the style of the dedication to Oxford. However, the same youthfulness poses new questions.- Where and when did he learn to speak Latin and French? (The dedication: AD PRECLARUM et nobilissimum Virum E O., serves as proof for his knowledge of Latin. His adeptness in the French language is demonstrated by the translation of Galien of France which was followed by further translations. Walsingham’s deployment of his services as a spy in Rome would not have been possible unless he had a good working knowledge of 16th century Italian.)

Thomas Aufield’s ironic remarks on Munday’s biography (in A true reporte of the death & martyrdome of M. Campion, 1582 ) bring us a step closer to the answer of the riddle. That is the reason why they are herewith quoted in their entirety.

“Munday, who first was a stage player (no doubt a calling of some credit), after an apprentice which time he well seemed with deceiving of his master[14], then wandering towards Italy, by his own report became a cozener in his journey. Coming to Rome, in his short abode there; was charitably relieved, but never admitted in the seminary as he pleaseth to lie in the title of his book, and being weary of well doing, returned home to his first vomit again. I omit to declare how this scholar new come out of Italy did play extempore, those gentlemen and others which were present, can best give witness of his dexterity, who being weary of his folly, hissed him from his stage. Then being thereby discouraged, he set forth a ballad against plays, but yet (O constant youth) he now begins again to ruffle upon the stage. I omit among other places his behaviour in Barbican[15] with his good mistress, and mother, from whence our superintendent might fetch him to his court [16], were it not for love (I would say slander) to their gospel. Yet I think it not amiss to remember thee of this boyʼs infelicity two several ways of late notorious. First he writing upon the death of Everard Hanse, was immediately controlled and disproved by one of his own hatch [brood], and shortly after setting forth the apprehension of M. Campion, was disproved by George (I was about to say) Judas Eliot[17], who writing against him, proved that those things he did were for very lucre’s sake only, and not for the truth, although he himself be a person of the same predicament, of whom I must say, that if felony be honesty, then he may for his behaviour be taken for a lawful witness against so good men.”

(A true reporte of the death & martyrdome of M. Campion, Iesuite and prieste, & M. Sherwin, & M. Bryan priestes, at Tiborne the first of December 1581. Observed and written by a Catholike priest, which was present therat. March 1582. )

We have seen that when Munday was apprenticed to Allde he was probably just over sixteen. If Munday had been on the stage prior to this time then surely only as a boy actor.

Seen in this context another statement from Aufield assumes new importance: “I omit among other places his behaviour in Barbican with his good mistress and mother, from whence our superintendent might fetch him to his court”. - Munday’s problems with his mother must have had their origins in early adolescence. That is why “our superintendent”, as Aufield jokingly calls him, bought the boy to his court to be a “boy actor”. But who was this “superintendent”?

The office of “superintendent” did not exist in Catholic circles; such an office was peculiar to Protestant circles and courts. We are reminded of Gabriel Harvey’s bon mot in Pierces Supererogation: “He [‘the sole author of renowned victory’] it is that is the godfather of writers, the superintendent of the press, the muster-master of innumerable bands, the General of the great field”. (See 3.1.6 Harvey, Pierces Supererogation.)

I.e. at some time during the course of 1574, Oxford will have fetched the young Anthony Munday to his court. At first he was a boy actor, then an apprentice of John Allde. When he had almost reached the age of eighteen, Sir Francis Walsingham sent him to Rome (with Oxford's permission) to spy on the Catholic mission. It is safe to assume that Munday was granted official permission to terminate his apprenticeship.

In view of Oxford’s anti-Catholic stand point, it is hardly surprising that we find a sardonic reference to the interrogation of the Catholic martyr Edmund Campion. The courtier Malvolio languishes miserably in the dungeon, the clown Feste plays the part of Sir Topas, the curate who interrogates him. [18]

MALVOLIO. Make the

trial of it in any constant question.

CLOWN. What is the opinion of Pythagoras concerning wild fowl?

MALVOLIO. That the soul of our grandam might haply inhabit a bird.

CLOWN. What think’st thou of his opinion?

MALVOLIO. I think nobly of the soul, and no way approve his opinion.

CLOWN. Fare thee well. Remain thou still in darkness. Thou shalt hold th’

opinion of Pythagoras ere I will allow of thy wits.

NOTES:

[1] my book intituled Galien of France. Munday probably translated the French version of a work from the Greek physician Galen (‘Galien’) into English. Dr George Baker's The Composition or making of the moste excellent and pretious Oil called Oleum Magistrale (dedicated to Oxford in 1574) was in the main an English translation from French of Galen’s Greek.

[2] and passed forward to Paris. Munday submitted a comprehensive and detailed account of his journey: ‘The English Romayne Lyfe; Discovering the Lives of the Englishmen at Roome, the Orders of the English Seminarie, the Dissention betweene the Englishmen and the Welshmen, the banishing of the Englishmen of out Rome, the Popes sending for them againe: a Reporte of many of the paltrie Reliques in Rome, their Vautes under the Grounde, their holy Pilgrimages, &c. Printed by John Charlewood for Nicholas Ling, at the Signe of the Maremaide,’ 1582.

[3] in hope I had been such a one as they looked for. That means that the people who helped Munday assumed that he was a Catholic.

[4] my Lord the English Ambassador then lying in Paris. Sir Amias Paulet (1532–1588) of Hinton St. George, Somerset, was an English diplomat, Governor of Jersey, and the gaoler for a period of Mary, Queen of Scots. In 1576 Queen Elizabeth raised him to knighthood, appointed him Ambassador to Paris and at the same time put the young Francis Bacon under his charge. Paulet was in this embassy until he was recalled November, 1579.

[5] take patient all adversity, and God will assist ye. With this statement Munday hoped to publicly establish a defense against eventual Protestant attacks.

[6] Faccio fine, è riverentemente baccio le vostre valorose Mani. / Humilissimo e Divotissimo e sempre Osservandissimo Vasallo e Servitore.

In closing I respectfully kiss your noble hands and will remain your / most humble and obedient vassal and servant; ever at your command.

[7] Not seeming once Bellona to despise, /For valiantness, behold young Caesar here, /Or Hannibal, lo Hercules in place. Munday adopts the same martial rhetoric used by Gabriel Harvey a year previously in his praise of the Earl (see 3.1.1. Gabriel Harvey, Gratulationes Valdinenses). Harvey uses the following words:

Take no thought of Peace; all the equipage of Mars comes at your bidding. Suppose Hannibal to be standing at the British gates; suppose even now, now, Don John of Austria is about to come over, guarded by a huge phalanx! … I feel it; our whole country believes it; your blood boils in your breast, virtue dwells in your brow, Mars keeps your mouth, Minerva is in your right hand, Bellona reigns in your body, and Martial ardor, your eyes flash, your glance shoots arrows [vultus tela vibrat]: who wouldn't swear you Achilles reborn?

[8] AD PRECLARUM et nobilissimum Virum E O. This Latin poem is placed at the end of The Mirrour of Mutabilitie.

[9] et morbo medicator acerbo. In the original text we find the fault: “et morbo mediator acerbo”.

[10] Nauta Mari … sentire ministram. – See 5.2.2 Oxford, Poems, No. 67, If fortune may enforce the careful heart to cry.

The soldier biding long the brunt of mortal wars,

Where life is never free from dint of deadly foil:

At last comes joyful home, though mangled all with scars,

Where frankly, void of fear, he spends the gotten spoil.

The pirate lying long amid the foaming floods,

With every flaw in hazard is to lose both life and goods:

At length finds view of land, where wished port he spys,

Which once obtained, among his mates, he parts the gotten prize.

Thus every man, for travail past,

Doth reap a just reward at last:

But I alone, whose troubled mind,

In seeking rest, unrest doth find.

Oh luckless lot.

[11] Alexis. At about the same time as Edmund Spencer praised Oxford (alias Cuddie) as a writer of comedies (see 3.3.1 Spenser, The Shepheardes Calender, notes 1, 6 and 12), Munday addresses his most respected mentor with “Alexis”.

Alexis (c. 375–c. 275 BC) was a Greek comic poet of the Middle Comedy period. He was born at Thurii (in present-day Calabria, Italy) in Magna Graecia and taken early to Athens, where he became a citizen, being enrolled in the deme Oion and the tribe Leontides. It is thought he lived to the age of 106 and died on the stage while being crowned. According to the Suda, a 10th-century encyclopedia, Alexis was the paternal uncle of the dramatist Menander and wrote 245 comedies, of which only fragments now survive, including some 130 preserved titles. He appears to have been rather addicted to the pleasures of the table, according to Athenaeus. - In Dropides Alexis says -

The lady gay then brought in the sweet wine,

In a wide silver vessel, very fine,

Neither bowl nor saucer, but like both.

[12] most fair and noble Lord (Lat. formose = fair, well-shaped). This choice of terminology brings Oxford into the vicinity of Euphues (Greek = the well-shaped man). Also John Lyly’s Euphues, “musing in the bottom of the Mountain Silexsedra”, refers to Oxford, Lyly’s patron. - See 5.2.4 Oxford, Poems No. 108.

[13] The author of this ‘Caveat’. The author was Thomas Aufield, an English Roman Catholic, educated at Eton College and King's College, Cambridge. He converted to Roman Catholicism and in September 1576 went to the English College at Douai. He was ordained a priest in 1581 at Châlons-sur-Marne and set out for the English Mission. In 1585 Aufield was arrested for circulating Catholic texts and sent to the Tower, and put to torture. He was then transferred to Newgate, tried, convicted and hanged at Tyburn, a reprieve arriving too late to save him.

[14] which time he well seemed with deceiving of his master. Munday’s master was John Allde, a Scottish stationer and printer. From 1560 to 1567 he received many licenses for ballads and almanacs, but for little else. He then began to print more books, chiefly of a popular nature. Allde lived ‘at the long shop adjoining to St. Mildred's Church in the Pultrie,’ and, judging from the considerable number of apprentices bound over to him from time to time, must have carried on a flourishing bookselling trade. – In 1582, John Allde categorically refuted the story that Munday had betrayed him. (See Anthony Munday, A Breefe Aunswer made unto two seditious Pamphlets, 1582.) This is probably associated with the fact that Anthony Munday terminated his apprenticeship prematurely to go to Italy.

[15] his behaviour in Barbican. The Barbican has a history almost as old as London itself. It was first built by the Roman invaders to protect what was for them a new settlement by the river. Within, in the area of the city just south of the Barbican, lived Martin Frobisher, Lancelot Andrews and Thomas More. The area of Cripplegate beyond the wall, was in comparison considered to be insalubrious and incommodious. In the 16th century it became the natural home for thieves and receivers of stolen goods. It was a microcosm of Elizabethan ‘low life’ and became the haven for nonconformists of every description. It was also a home for actors. Will Shakspere lived here at the corner of Monkwell Street and Silver Street. Ben Johnson lived for a period in the Parish of St. Giles. Grub Street was perhaps the most famous of the Barbican streets, and it has remained in the popular imagination ever since it was described by Samuel Johnson as ‘much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries and temporary poems.

[16] from whence our superintendent might fetch him to his court. See Gabriel Harvey, Pierces Supererogation (1593): “Nay, Homer not such an author for Alexander, nor Xenophon for Scipio, nor Virgil for Augustus … nor Aretine for some late Courtesans, as his Author for him [Nashe], the sole author of renowned victory … he [Nashe’s Author] it is that is the godfather of writers, the superintendent of the press, the muster-master of innumerable bands, the General of the great field; he and Nashe will confute the world.” – OED: “superintendent. An officer or official who has the chief charge, oversight, control, or direction of some business, institution, or works.”

[17] and shortly after setting forth the apprehension of M. Campion, was disproved by George (I was about to say) Judas Eliot. George Eliot is reported to have been an unsavoury character. He earned his living as a confidence trickster, but was well known as a rapist and suspected of being a murderer. He entered the service of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester as a spy to avoid a charge of the last crime and agreed to seek out recusant Catholics and hand them over to the authorities.

[18] Feste plays the part of Sir Topas, the curate who interrogates him. In Feste’s speech there are no less than five phrases that refer directly to Edmund Campion and his 1580-81 mission to England. – See C. Richard Desper, Allusions to Edmund Campion in Twelfth Night, Elizabethan Review 1995.